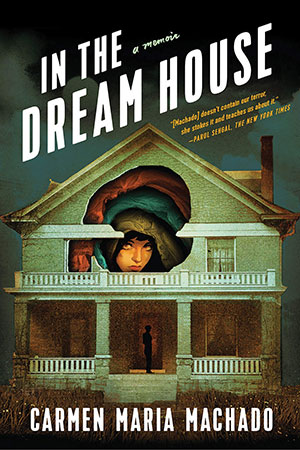

In the Dream House: A Memoir by Carmen Maria Machado

New York. Graywolf Press. 2019. 247 pages.

New York. Graywolf Press. 2019. 247 pages.

“Writing is a way to get rid of shame,” says Karl Ove Knausgaard, reflecting on why he wrote his celebrated 3,600-plus-page-long multivolume memoir, My Struggle. Indeed, autobiographical outpourings can have a cathartic effect—of cleansing—on the writer’s soul. In her 2019 memoir, In the Dream House, Carmen Maria Machado writes not only to ameliorate self-suffering but also to disabuse readers’ notions about lesbian love. This love, according to Machado, has been etherealized into an ideal attainable without “men’s accompanying bullshit.” Yet, as Machado contends, historically, lesbian love is not immune to the oppressive structures of patriarchy. It’s just as fraught and fractured as heterosexual love. Moreover—and shockingly so—queer love, like its straight counterpart, can engender intimate partner violence. In her memoir, Machado contests these notions by foregrounding her own experience of being in an abusive relationship with a woman. The lesbian domestic space in Machado’s telling is neither tranquil nor transcendental.

However, the telling is a struggle because an aporia looms large at its center. Machado writes that she has no “language” in which to reconstruct her memory of the haunted dream house. The details of the terror are (intentionally) amorphous; the woman is described as slight and blonde; the woman’s house in Bloomington, Indiana, lacks materiality, transformed by the woman’s implausible and uncontrollable rage into a dark, gothic chamber of fear. Machado attributes her narrative predicament to an “archival silence,” a word that poignantly captures the idea that certain histories—the history of queer domestic violence being one—never enter the cultural records; at best victims of such violence find themselves telling their stories in a vacuum or, at worst, they stay silent. To make a coherent narrative in contextual “silence,” Machado invents a language and a form to make her particular history legible.

Lacking a prefabricated house, Machado imagines an archive and dreams up an architecture in which her narrative can live, girded by literary artifacts—prologues, quotes, epigraphs, references to theories and pop culture—that lend the narrative a certain legitimacy. In other words, the introductory quotes and the subsequent epigraphs are not mere literary gloss; they are the bricks with which she lays the foundations of her narrative “home.” The resulting form is spectacular. The contents of short chapters are foreshadowed by loaded headings like “Dream House as Confession” or “Dream House as Fantasy.” The relationship between the titles and the actions contained in sections is fluid and dynamic, but the aim is razor sharp: to illuminate the complexities of queer love from shifting angles.

In the Dream House exudes not only artistic but also political valence. At the heart of the memoir is a subtle critique of queer complicity in suppressing inconvenient truths of gay love, especially love that goes awry in the domestic space. Having fought to win the basic civil right to love and marry freely, the gay community may be loath to admit failure of their ideal, lest they be laughed at by the patriarchy against whose imperfect grain gay love often defines itself. But the theorizing notwithstanding, Machado’s memoir answers a question about lesbians unflinchingly: If you ask whether domestic violence is possible in a lesbian household, Machado’s response would be “Hell yeah!”

Sharmila Mukherjee

Bronx Community College at CUNY