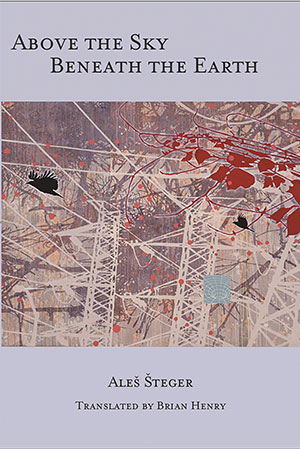

Above the Sky Beneath the Earth by Aleš Šteger

Buffalo, New York. White Pine Press. 2019. 75 pages.

Buffalo, New York. White Pine Press. 2019. 75 pages.

What is it about Slovenian poets that continues to tickle American readers? The most famous of them, the late Tomaž Šalamun, was simply fun to read. What’s more, beneath their surreal façades, his poems hid a voice wrestling with fundamental questions about the human condition. Is that it, then? Fun and games coupled with irony, that most famous eastern European poetic ingredient? To be able to combine humor and absurdist turns of phrase with serious meditations on ethics and history is hard to pull off, yet in the hands of the Slovenians it never feels contrived.

Aleš Šteger (b. 1973) continues in this vein, though this latest volume to be translated by the inimitable Brian Henry, himself a fine poet who’s learned a great deal from the poets he’s translated, is a bit different. First of all, it’s much quieter in tone than we’d expect. Gone are the histrionics and the pyrotechnics. Divided into three sections, “Beneath the Earth,” “Field of Audibility,” and “Above the Sky,” the untitled poems consist of mostly declarative sentences, many of which are end-stopped with a period. The effect is both jarring and engrossing, for while the rapid succession of precise lines can dull our senses, their wisdom, if you will, hinges on the poet’s ability to communicate his thoughts and feelings in a way that is greater than the sum of their individual parts.

In his blurb, Ilya Kaminsky singles out the volume’s third poem—my favorite lines in what is certainly a fine poem: “The day arrives like a poem / In a lost language”—but there are plenty of gems throughout. “Between truth and man / I choose waiting,” declares the speaker of another poem in the book’s first section, and I’m immediately hooked. Recording his peregrinations around the world in the second section—from Japan through Argentina and on to Germany, especially Berlin, which has become an important focal point for Šteger—the poet reminds us that “A mistake is / A part of perfection. / A lie, a part of the truth.” This dichotomy plays out repeatedly in these poems, which depict the poet’s penchant for thinking aloud about the cause-and-effect nature of things. When Šteger writes toward the very end of the book, “A poem nests / In my head. / Where is its home? / Everywhere,” we’re in luck indeed.

Piotr Florczyk

University of Southern California