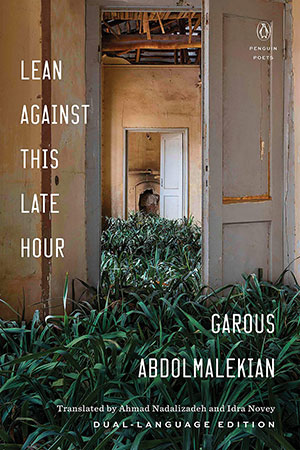

Lean against This Late Hour by Garous Abdolmalekian

New York. Penguin. 2020. 160 pages.

New York. Penguin. 2020. 160 pages.

Despite disparities in time, space, and language, even in translation, Baudelaire’s address to the reader (“—Hypocrite reader,—My duplicate—My brother!”) has a particular way of feeling personal, as though it is you, the embodied reader, and not a general, undefined public, who is implicated in the hypocrisies that the speaker has in mind. The address is direct, to be sure, but, perhaps more interestingly, it also creates a sense of immediacy because it is delivered in such an obviously affected stage voice. That is to say, it is easy to locate yourself in Baudelaire’s hypocrite reader in large part because the poetic voice resists a literal, autobiographical reading. You assume that the real person named Charles Baudelaire did not in fact experience “the deadly poison, daggers . . . Monsters screaming” and so on that are so vividly invoked. Rather, the use of stage voice, the overt and deliberate dissociation of the poetic “I” from the historically occurring individual who composed the words or, for that matter, the dissociation of “you” from anyone in that poet’s personal life, opens a possibility for a different kind of correspondence between the reader and the text. If you see traces of truth in these images, imaginaries, and imaginative words, the poem seems to say, then it is because you have performed your own subjective interventions, not because the words correspond to an empirical reality outside the text.

Garous Abdolmalekian lives in our own time and writes in an unadorned language resembling the patterns and cadences of everyday speech. Little surprise, then, if we can locate ourselves within the world that his poems create. Like Baudelaire, however, it is Abdolmalekian’s stage voice that most remarkably draws us in: “in me there are characters / who stab each other / in the cemetery of my psyche / but I / with all of my characters / go on caring for you.” Lean against This Late Hour, a dual-language collection of Abdolmalekian’s Persian poems alongside English translations by Ahmad Nadalizadeh and Idra Novey, invites a growing audience to participate in the theater of the Iranian poet’s words. Certainly, there will be readers drawn to this new collection because they want to hear what a young (Abdolmalekian was born in 1980), relatively successful poet writing in a country that often appears in headlines for all-too-familiarly unpoetic reasons has to say. But, be warned, potential reader: Abdolmalekian’s voice resists facile autobiographical readings, despite—or perhaps because—his words often sound like expressions of real, lived experiences. The speaker’s invocation of a brother killed in an unnamed war, for example, felt so personal that it sent me scrambling to the internet to find out whether the poet has or had a brother himself (spoiler alert: the answer is no): “the curved posture of my father / who after years / has yet to take my brother’s corpse / off his shoulders / and place him in the ground.” Indeed, if Abdolmalekian’s “I” is not the same as the poet and his other characters are not individuals from his life, then the “you” must be comparably shifting and unstable. This is artifice, the poems say, so it is you, with all the baggage of your lived experiences, who binds them to the historical realities of your given moment: “I modified the poem here / and pulled time out / like a thread.”

Critical opinions on approaches to translating poetry will no doubt vary almost as widely as the approaches themselves. Some translators choose to remain so loyal to the literal meanings of the words that they forgo any possibility of a readership outside of a self-contained circle of philologically minded scholars. At the other extreme, some translators commit themselves so fully to the receiving language’s demands that the text becomes unrecognizable as translation at all. Nadalizadeh and Novey’s style falls somewhere in the middle of that spectrum and might be called “poetic translation.” While there is a clear and often direct correlation between the Persian words on the left-hand pages and the English on the right, the English is also rife with departures, silences, and even some insertions that suggest that the translators had more than the literal or surface meanings of the Persian words in mind.

My own opinion is that poetic translation alongside the original text offers those who can enjoy both languages a rich reading experience, raising any number of open-ended questions about translation as a creative (i.e., subjective) act. One might be struck, for example, by the way that the translators insert humans into the line “Humans cannot hide the hidden” when the Persian reads literally as “the hidden cannot be hidden.” What, one might then ask, are the implications—aesthetic, semantic, ethical, or otherwise—of inserting humans into what was an impersonal construction in the Persian? But let us assume that the translation, too, is unbound from the experiences or intentions of the translators. Then we might begin to see just how fully a poetry like Abdolmalekian’s implicates your own subjective interventions in its becoming meaningful and real.

Samad Alavi

University of Oslo