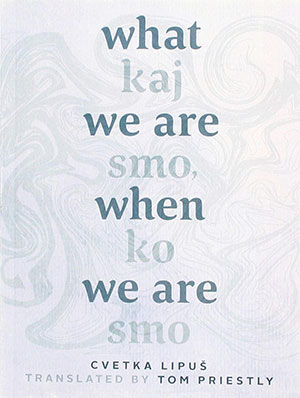

What We Are When We Are / Kaj Smo, Ko Smo by Cvetka Lipuš

Edmonton. Athabasca University Press. 2018. 108 pages.

Edmonton. Athabasca University Press. 2018. 108 pages.

This book of translated poetry deserves strong reactions, and it both evokes and earns them. It is a complex if short work, and one’s responses might not be immediate, but they will come. As each of the thirty-two poems here adds its insights to the ones before, and as the sureness of Cvetka Lipuš’s poetic vision becomes more apparent, we cannot help but be grateful that the author has let us inside these deeply humane thoughts of hers. We are also likely to be more than a little bit in awe of the consistency and calm insistence of her language; this is high artistry. We might also be grateful for the aptness of the title, which, reinforced by thoughts from the brief foreword, impresses on us the unity and mission of this project, a testing, a plumbing, of our nature (I won’t say identity) in the long game that is cached or aggregated experience (I won’t say life).

Cvetka Lipuš is a Slovene from the Austrian state of Carinthia. This is her seventh book of poetry since 1988, and she is the recipient of a number of significant awards in both Austria and neighboring Slovenia; it is high time that her work circulated in the anglosphere. And we are off to a great start in that regard, because this collection has been rendered into luminous, inviting English by Tom Priestly of the University of Alberta; his sophisticated translation, built on intricate diction and topical accuracy, nobly and ably underscores the unifying beauty of Lipuš’s writing.

Many of these poems are rigorous in their formulation. They deserve to be closely read, closely heard, as they walk us along the frontier of the unconscious. Indeed, motion is a key feature in most of the individual works. The words and images are in constant movement, not just in the simple sense of journeys but by evocations of rivers, clouds, tsunamis, navigation, orbits, the speed of light, tornadoes, trains, cosmonauts, ladders, breezes, and, yes, deaths. The motion is open-ended: begun, for whatever reason (sometimes dread), but not necessarily completed. Some of the poems take us out of ourselves completely, as when the author refers to being older than herself, getting accustomed to herself, stepping out of her memory, or, in a manner devoid of neither charm nor melancholy, checking the mailbox to see if she is there. Some of the works, such as “The Dream,” “Sleeplessness,” or “Employment,” qualify as surreal or Borgesian; “Open End” contains brilliant existentialist reflections on (auto)biography. Two of the poems stand out to this reviewer for the beauty of their representations of multigenerational families and midlife happiness: “Perpetuum Mobile” and “Dreams Limited.”

Lipuš’s work is intense and philosophically inclined. It aims not at pyrotechnics or confession, or at history or politics, or at morale or morality. But it feeds the brain, in every positive sense, as well as fills the heart; this is because its ends and means are, arguably, so enmeshed and coordinated. This is poetry that is powerful and erudite (in the right, procedural and not encyclopedic way) and quiet, even patient: arguably what we are hearing is supreme, supple artistic confidence, and the silence arises from our reading, thinking, and rereading.

John K. Cox

North Dakota State University