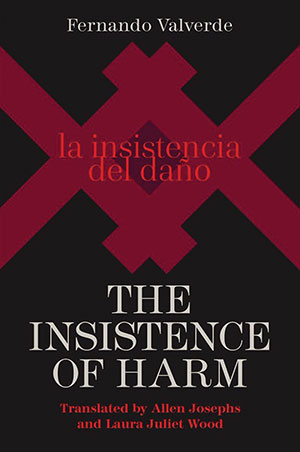

The Insistence of Harm by Fernando Valverde

Gainesville. University Press of Florida. 2019. 133 pages.

Gainesville. University Press of Florida. 2019. 133 pages.

Fernando Valverde, born in 1980 in Granada, is at the forefront of the “Poetry of Uncertainty,” which emerged in the early 2000s in Spain. The poetry of uncertainty explores how poetic language confronts the slipperiness of reality and meaning-making processes. Rather than being simply an intellectual conceit, however, the poetry of uncertainty crafts touchpoints of language, often highly imagistic, to trigger a flow of emotion to make the act of reading and interpreting poetry a highly personal experience. Like the ultraists of the early twentieth century, they emphasize the production of emotion.

Valverde incorporates the concept of harm, which is in essence a poetic mechanism rather than a specific account of an event or an atrocity. “Harm” evokes what Valverde describes as “future nostalgia” and triggers one’s personal reflections of events and people, along with a deep sense of appreciation.

In “Celia,” the world is physically uncertain and “mapas no aseguran un lugar donde ir / maps do not guarantee a place to go.” Further, juxtapositions of the real and the extraordinary introduce an element of the fantastic. Nevertheless, in the middle of the poem, he writes, “es esa mi certeza / that is my certainty,” creating a point of certainty, thus allowing the reader to move multidirectionally in the text for emotionally anchoring connections.

Valverde expresses uncertainty (and the state between real and unreal) as metonymies, including fog, vertigo, trackless woods. This is the primordial energy from which meaning arises and just as quickly slips back into the muffled, fogged, and trackless mind of beginning and ending. In “Un camino hacia ti,” Valverde takes the reader into the “dangerous woods” of the unknown, of the unconscious. And yet, from that sense of existential unmooredness, Valverde’s poem generates a great sense of relief, knowing he has a “road back to you” / “camino hacia ti.”

In the section “Sadness in Maps,” the poems relate to a specific place of tragedy or harm, each of which results in deeper consciousness about life, death, and the passing of love. They also generate a sense of anticipated nostalgia, which characterizes Valverde’s poetry. In “Puebla,” there is resignation, and in Potocari, “Los Muertos siempre dejan / un silencio apremiante / o los últimos pasos / que convierten a un hombre / en desaparecido” (The dead always leave / an urgent silence / or the final steps / that make a man disappear).

Finally, in “Harm,” Valverde describes “future nostalgia” and the linguistic and poetic mechanism used in eliciting flows of feeling and meaning. The process is painful, and yet the pain and the poetic mechanism of “harm” are what lead to expressions of beauty and an ability to capture fragments of life and sparks of light.

Susan Smith Nash

University of Oklahoma