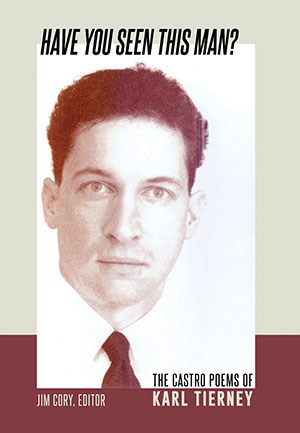

Have You Seen This Man? The Castro Poems of Karl Tierney by Karl Tierney

Little Rock, Arkansas. Sibling Rivalry Press. 2019. 120 pages.

Little Rock, Arkansas. Sibling Rivalry Press. 2019. 120 pages.

The United States is a young country, yet few phenomena that occur here are new. The AIDS epidemic is one of the foremost among the handful of tragic exceptions. Since the height of its brutality, both those who survived and those who were outside its grasp have turned to those who wrote in the face of it to try and comprehend its cultural significance as well as process its fallout. Karl Tierney is a recent addition to the published canon of poets who wrote during the crisis, but his contribution cannot be overstated. Drawing together time and space, Tierney uses poetic words and biting wit to simultaneously personalize and universalize his experience as a gay man living in San Francisco’s Castro District during the height of the epidemic.

The poems in Have You Seen This Man? are arranged in chronological order. This sequencing serves to reinforce the memoiristic bent that is already so often presumed with writing of his era, but everything else about the text and tone undercuts what a reader may expect. Tierney’s personal story is a tragic one. After moving from Arizona to San Francisco in 1983, he was diagnosed with AIDS in 1994, and when he was turned down for treatment, he jumped to his death from the Golden Gate Bridge. When his mother entered his apartment, she found a note, his wallet, and a message on the answering machine saying there had been a mistake: he was qualified for the experimental study.

Tierney’s poetic perspective is not one of melancholy, however. He draws direct inspiration from Catullus, borrowing his style of biting, bawdy satirical humor as well as his form of direct-address poems to add an edge and avoid the device of writing to the dead or dying so common in AIDS poetry. Even the best poets need editors, however, and it is unfortunate that Carl was not alive to work with one, as some poems in this collection are a draft or two away from their full potential.

Yet to call Tierney an “AIDS poet” trivializes his work, for, as his literary executor and friend Jim Cory said at a reading in St. Paul recently, “He was looking at [the crisis] in a micro way, but also in a very global, universal way.” Tierney’s voice is one that transcends his time period, reminding us brightly and bitterly that “Great Causes / cannot be swallowed whole.”

Linda Stack-Nelson

Minneapolis