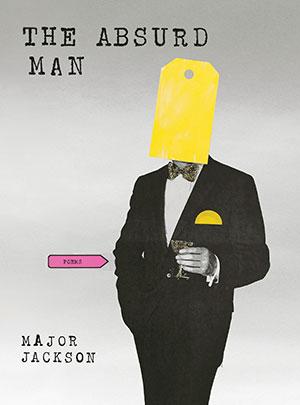

The Absurd Man by Major Jackson

New York. W.W. Norton. 2020. 112 pages.

New York. W.W. Norton. 2020. 112 pages.

Major Jackson’s fifth book of poems is troubled by its own age. “The soil overruns with honey,” says the speaker in “I’ve Said Too Much,” a confession ripe with seasons of overindulgence. But satiety may not quite be what Jackson has in store for us this time. As though it had spent the five years since the release of Roll Deep (2015) weighing a smattering of gray hairs before embracing salt-and-pepper, The Absurd Man brings a different feel to Jackson’s perennially strong poetry. With a dose of self-awareness that is by turns playful, thought-provoking, and heartbreaking, the poems in this book offer up a collective narrative to complement their stand-alone lyricism.

Return readers will mark a change in this book’s “Urban Renewal” suite, a recurring, sequential section that Jackson has described as a sort of autobiographical bildungsroman spread out across his collections. As in the book’s earlier poems like “November in Xichang,” the poetry in this section deploys Jackson’s signature roaming ekphrastic. But, often, Jackson doesn’t quite rhapsodize, leaving us a handbreadth short of the rapture of his habitual syllabic alchemy. Ultimately, his keenest lyric notes come not in poems like “Paris” but in the last half of “North Philadelphia” (the home of Jackson’s youth): “tunes / not so much learned yet risen, earth’s laments / gardened in our throats from black soil, a slow grumbling, / fitful drawn-out grunts grafting onto gospel notes / not recognized but felt, a ring-shout.” He ends, “I’m still in that dimness, several rows behind their wails, / writing their moans so you can feel them like Braille.”

In The Absurd Man, the tune of Jackson’s most tactile, Braille-like passages takes after Albert Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus, whose epigraph heads the section, valorizing the art of “the absurd creator.” In many ways, though, the epigraph toes the line between being a deceptive frame and an ironic foil, a presiding duplicity the reader is alert to from the book’s coy opener, “Major and I,” a playful take on Jorge Luis Borges’s “Borges y yo” that similarly exploits the sometimes troubling implications of a writer’s multiple personae.

Indeed, the speaker resists the absurd in the latter poems of “Urban Renewal,” which are a diminuendo of despair weakly combatted. Both the pristine landscape of “Double View of the Adirondacks . . .” and the blasted mountain barrenness of “The Valkyrie” equally prompt the speaker to somber existential realizations—“My crimes felt mountainous . . . I’ve no true friends, my verse’s / mediocre at best, a white captivity”—that attempt, in the last octet or so, quick reversals through transcendent symbols. A speaker who once trumpeted poetic triumph now becomes self-reflective, chasing a dram of venomous self-castigation with the occasional attempt at antidote, a flinch from the absurd. The reader who calls bullshit finds affirmation in the sobering confession of “Augustinian,” the third poem in the book’s titular collection. In the end, this is not a volume in which redemption undoes the fall.

And so we come to “The Absurd Man Suite.” Drawing its name and inspiration from a chapter of The Myth of Sisyphus, the book’s final section is an arc of loves, lusts, and pensive mornings-after that pencils a discourteous portrait of the artist as dilletante. Boasting wry titles like “The Absurd Man Swipes Left in New York,” the poems have the air of a pileup of perfumes from a month’s worth of one-night stands. The risk of repetitiveness is offset by Jackson’s knack for form and rhythm play. In “Why the Absurd Man Doesn’t Dance Any More,” strobes of sensation pulse in enjambed tercets, a quick whirl that stirs the heavy scents out of stagnation.

In the penultimate poem, “The Absurd Man in the Mirror,” the recurring symbols of indulgence, reflections, and mountains rear once more, this time not unkindly as “winter mountains reach / across a page the color of honey.” The book’s final line—“You’re smiling, and that’s all / the defending I’ll ever need”—leaves us with the sense that there is no reason that tomorrow should not be perfectly pleasant, just as there is no reason that it should be. No reason at all—the least possible amount of promise.

A standout collection with many a standout poem, The Absurd Man leans heavily into themes of family (“My Son and Me”) and, as ever, pays homage to peers and predecessors (“Dear Zaki”), but it also traffics more deeply in symbols than books previous. Multifaceted connections between pieces create a compelling array of narrative, lyric, and symbolic arcs, joined or joinable, that mutually suggest a way of being that I’ll dare to call “deeply human,” in that it strips away any flattering illusions as to what exactly that means.

Grant Schatzman

Philadelphia