Incidental Inventions by Elena Ferrante & Elena Ferrante’s Key Words by Tiziana de Rogatis

I

I

Incidental Inventions. New York. Europa Editions. 2019. 117 pages.

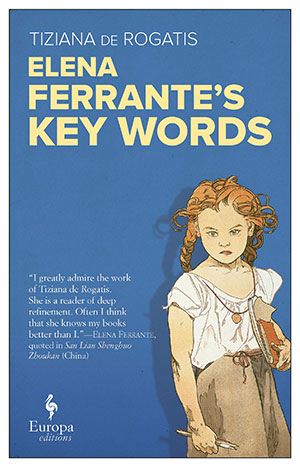

Elena Ferrante’s Key Words. New York. Europa Editions. 2019. 308 pages.

IN OCTOBER 2016 the journalist Claudio Gatti “unmasked” the mysterious Italian author Elena Ferrante as Anita Raja, Edizione e/o’s German translator and wife of the novelist Domenico Starnone. “Foul,” tweeted her readers, fearful that this violation of her privacy would stop the flow of her words. Ferrante had, after all, always insisted that anonymity was vital to her creative process. “I believe that books, once they are written, have no need of their authors,” she wrote to her publishers in 1991, declining book tours, interviews, and other public engagement.

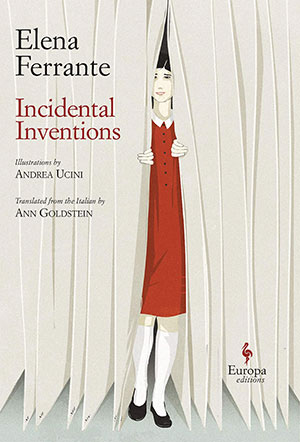

Within a year the Guardian announced that Ferrante had agreed to contribute weekly columns, which Europa (Edizione e/o’s English-language imprint) has collected and translated as Incidental Inventions. As always with a Ferrante book, the cover is a tease. This one shows an adult, dressed like a schoolgirl, who peeks out from behind a parted curtain. The preface and tone of what follows all support this persona of a child-woman: shy, fearful of public speaking, unadventurous. She “was flattered and at the same time frightened” by a project that “scared and inspired her.” Yet Elena Ferrante has twice published opinion pieces in the New York Times, once to attack the Camorra for letting Naples drown in its garbage (Jan. 2008); more recently, to rally women writers to seize their power (May 2019).

What are we to make of platitudes like “What perhaps should be feared most is the fury of frightened people” or “Beliefs aren’t good or bad; they serve only to bring order, at least momentarily, to our anguish” or “We can be much more than what we happen to be”? One piece, “The Male Story of Sex,” bemoans the usual heterosexual romance, whereas recent films and books by women (Portrait of a Lady on Fire comes to mind) offer a variety of forms of female desire, as do the Neapolitan novels.

There’s nothing here that wasn’t covered in Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey (2016) to greater effect. In a column called “Digging,” for example, Ferrante writes: “Restraint is all wrong if the task of the writing is to sweep away the resistance of the ordinary and look for words that will pull out at least a little of the extraordinary that is concealed in it. What is not suitable to say should, within the limits of the possible, be said.” Compare this to: “It is better to go wrong with the incandescent lava inside us, it is better to appear revolting for this reason, than to ensure success by playing it safe” (Frantumaglia, my translation). Or, again from Frantumaglia, the novelist explains how she uses loss of control to strip away the armor of her character’s good education and manners: “I enjoy upsetting her self-image, her will, and revealing another, rougher soul underneath, someone raucous, maybe even crude.”

Inventions reads like diluted Ferrante, whereas Frantumaglia is the work of a seasoned writer with a lot to say about what has worked for her and what doesn’t. Surely, the same person who created the memorable characters Lila and Lenù of My Brilliant Friend, the raging jilted housewife of The Days of Abandonment, and the mother who enjoys a fatal last swim in Troubling Love didn’t write these columns for the Guardian. So as a reader, I am back in the labyrinth: Who wrote these words, and for what purpose?

Certainly part of the problem is that essay topics were chosen by the Guardian at Ferrante’s request. What can you say about ellipses or the exclamation point or plants or clean breaks or black skies? Not a lot, as it happens. These made-to-order exercises offer few insights into what drives this writer. She admits to a game in which she changes the gender of male protagonists in famous stories—she uses Hawthorne’s “Wakefield”—to see if the new story would work. It doesn’t with “Wakefield,” and she concludes that his character, “who is present and absent like an idle divinity, simply watching, intervening, seems to me inevitably male.” Lila’s disappearance—an event that triggers the Neapolitan novels—clearly springs from Ferrante’s interest in this notion of an absent presence. Similarly, her thoughts on jealousy, dying young, mothers, and gender bias in literature seem rooted in lived experience. Yet the best one can say about these personal essays is that they take pains to avoid the personal.

The question of Ferrante’s identity was declared off-limits by her publishers twenty-eight years ago, but is it only the obsession of a parasitic press, as Tiziana de Rogatis claims in her critical study, Elena Ferrante’s Key Words? In many ways her book breaks new ground for its deep analysis of the novelist’s themes and insights into recent Italian history and culture.

As a Neapolitan, de Rogatis has “street cred”: she knows the world and language of these characters intimately; as a professor of comparative literature at Siena’s University for Foreigners, her classes in feminism and modern literature give her a platform to discuss Ferrante’s literary ancestors as well as her contemporaries.

With such rigorous intellectual tools, why, then, does she devote an introduction and conclusion to the Italian novelist’s commercial success in hyperprose that would make a publicist blush? My advice is to dive into chapter 2 on female friendship, where de Rogatis identifies Ferrante’s break with tradition in making Lila’s and Lenù’s intense relationship, not an adjunct to, but the heart of the Neapolitan novels. “Disorderly” is how she describes this symbiosis—Ferrante’s word—and it’s a bumpy ride, up and down, for sixty years. She points to the girls’ flawed relationships with their mothers as driving their emotional need and, with that, a refusal of male codes. They don’t want to end up like their mothers and grandmothers, “as angry as starving dogs.” Each girl will adopt different strategies to free herself, and tracing their alternating pattern of support and competition from childhood to old age is one of the novelist’s great gifts to fiction.

Though de Rogatis covers all of Ferrante’s fiction and nonfiction, she focuses on the Neapolitan novels, a multifamily saga she calls “a biting critique of [the institution of family], a rewriting of the sentimental, idealized myth that views the poor Neapolitan family as loving and mutually supportive.” Certainly the sympathetic reaction of neighborhood families to Stefano’s battering of his new wife confirms that; he’s teaching Lila a lesson, they say. In “The Labyrinth of Violence,” the author unpacks the nature of male abuse and the women who perpetuate it.

De Rogatis credits the novelist with destroying two popular myths: first, the myth of unconditional motherly love; second, the myth of the Mediterranean matriarchy as omnipotent and essentially different from male domination. Another Ferrantian innovation, per the author, is that Neapolitan dialect isn’t cute and cuddly but offensive and obscene—as experienced, for example, by Delia in Troubling Love. Immersion in these sounds can lead to another Ferrantian neologism, smarginatura, a feeling that one’s world is breaking apart.

De Rogatis is especially effective in delineating Ferrante’s use of dialect versus standard Italian as, for example, Olga’s reversion to dialect during her unspooling in The Days of Abandonment, or Leda’s disgust at hearing a family of Neapolitans at the beach, or Lenù’s many linguistic disguises. As a plebian, Lenù must use proper Italian in sync with her social ambitions and as a woman pretend to be “male in intelligence.” But Lenù’s return to Naples in the final novel confirms her role as a bridge between outsider and insider. She is both—or as de Rogatis puts it—“the one who leaves is the one who stays.”

De Rogatis defines the Neapolitan novels as “hyper-genre,” which she compares to Elsa Morante’s House of Liars, drawing on sources of high and low literature—magic realism, thrillers, bodice-rippers—to create a timeless web where plot, not history, matters. Yet, as mentioned, de Rogatis’s claims for Ferrante as a novelist are confused with hype we don’t need. A circular statement like “The quartet is considered a central and highly innovative global novel because the international success of this sweeping narrative cycle is rooted in a ‘glocal’ language, space, and imaginary created by the author” are part of a promotional clutter better left to Ferrante’s marketing team. When the brand “Elena Ferrante” threatens to overtake the simple joy of reading her stories, we are diminished.

For that reason, we can’t wait for Ann Goldstein’s translation of La vita bugiarda degli adulti, Ferrante’s first novel in four years, to hit bookstore shelves in June 2020.

Lisa Mullenneaux is the author of Naples’ Little Women: The Fiction of Elena Ferrante (2016) and translates modern Italian poetry. She lives in Manhattan and teaches writing for the University of Maryland GC.