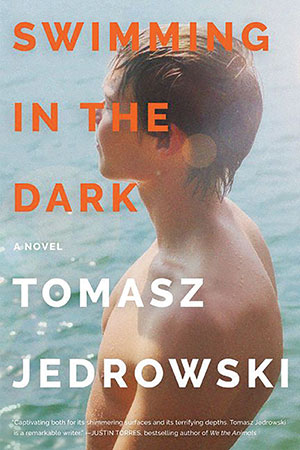

Swimming in the Dark by Tomasz Jedrowski

New York. William Morrow. 2020. 195 pages.

New York. William Morrow. 2020. 195 pages.

An author who wishes to recall a history known to his parents, but outside his own experience, often has a hard time getting it right. He may brim with overconfidence about what life was like back then but may miss many of the subtleties.

Tomasz Jedrowski’s parents migrated from Poland to western Germany as the short-lived Solidarity period was crushed by the Polish Communists. Born in Germany, Jedrowski earned a law degree at Cambridge, attended the University of Paris, and now is based in Poland surveying national identity and fashion.

Fluent in Polish and four other languages, the question nevertheless arises whether the novel could only have been conceived in England. His sensibilities mark him as a product of multicultural, super-diverse, LGBTQ-receptive England. He writes of his debt to a London writing group even though the narrative is set in Poland. He has been critical of a French gay publication for not treating gays as ordinary people. How then must he find life in Catholic, conservative Poland?

Many English-language publishing houses competed for the rights to his manuscript. It is a love story between two young men, one more invested in the relationship than the other, and why they drifted apart in the tumultuous politics of 1980s Poland. Ludwik, the student narrator, comes out at a time when gays had no role models to follow. To be sure, several literary cafés in Warsaw and Kraków were open to gay people (Spartacus International Gay Guides listed several), but a sense that they were under surveillance was palpable.

Ludwik is besotted by Janusz, a pro-Communist activist convinced the party would remain in power for years to come. Janusz admonishes his lover: “I told you we mustn’t take risks. You want to protest? What for? To end up in prison and to be a martyr for nothing?” But his scorn for politics deepens as his attraction for Ludwik fades, poignantly captured in Jedrowski’s writing.

Perhaps the writer was inspired by the plot of a film forming part of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s iconic ten-part Dekalog series—Przypadek (Blind chance). It relates three storylines in quick succession having differing outcomes. In the first, medical student Witek becomes entangled in Communist politics; in the second, he is radicalized and joins the dissident movement; in the third, “blind chance” renders Witek’s political choices irrelevant. Censors held up Kieślowski’s film until it was released in 1987, but Jedrowski faces no such obstacles.

Martial law with a Polish face began when General Wojciech Jaruzelski delegalized Solidarity even as liberal politics festered underground. Solidarity head Lech Wałęsa disappears and reappears during this decade. Decadence accompanies austerity; well-connected youth are especially privileged. At an ornate mansion outside Warsaw, self-abnegating Ludwik becomes spaced out by alcohol and edibles. Janusz alerts Ludwik to the irony: “You’re the one who didn’t see a future in our country. . . . Here it is.”

When Janusz realizes that his career will be boosted by a demonstrable heterosexual relationship, Ludwik is brokenhearted. It’s a short step to the dependable exit strategy of that era—immigration to America.

One plot driver is a book shared by Janusz and Ludzio, James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, telling of “discrimination and shunning” that targets “the Negro in American society.” Ludwik embraces it in writing his doctoral dissertation: “I could see its relevance, could see how it exposed the double standards of the West, how it showed racism and white supremacy behind the liberalism and democracy extolled by the capitalist powers. At the same time, of course, I could identify. I carried my difference, my shame, on the inside. It wasn’t visible—not to everyone straightaway, at least—but it was there, and it was a danger.”

For Jedrowski, a notorious precedent for stigmatizing homosexuals in People’s Poland was Michel Foucault’s visit to Warsaw in 1958. He finished The History of Madness but was ensnared in a honey trap with a gay man and expelled from Poland. The vibrancy of Swimming in the Dark is a love story that lapses when homosexuality cannot find space in the 1980s. Forty years later, the battle for that space, sadly, continues.

Ray Taras

Tulane University