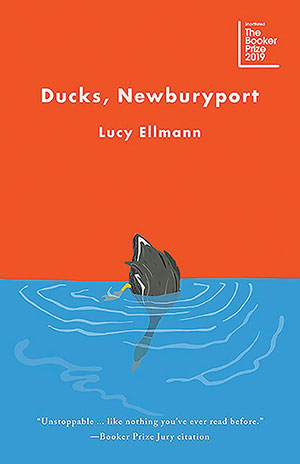

Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann

Windsor, Ontario. Biblioasis. 2019. 1020 pages.

Windsor, Ontario. Biblioasis. 2019. 1020 pages.

Ducks, Newburyport opens with a quiet moment of motherhood: a lioness contemplating the awareness of her cubs and the absolute necessity of her being. Life hinges on food and warmth and protection. A page later, human reality interrupts nature as a fast-paced voice permeates the brain. Here, self-awareness meets stream of consciousness, free association meets tense subliminal connections, and a single sentence proceeds for nearly one thousand pages.

We vacillate between motherhood and personhood, between housekeeping and clickbait, between rumination and avoidance. Our narrator is a stay-at-home mother who describes herself as “at the mercy of four little American brats.” Initially, her narrative is not so much a story as a play-by-play of her daily life, thoughts, and memories, with occasional analysis and clarification, though she stops short of probing her deeper feelings. She holds back nothing when it comes to wordplay and associations, and often words and images snowball into a chaotic thought that ends figuratively but never literally.

Each thought begins with “the fact that,” but the narrator is not merely aware of these so-called facts. She has fully internalized them, blurring the space between fact and statement, blurring the space between self and the external world. A random Seinfeld line stands alongside personal memories that appear no more meaningful than plots from Laura Ingalls Wilder. As I read, the gap between her thoughts and the outside world diminishes further; her thoughts become my own, paralleling the ways that noise becomes our normal. Her facts blur with my own broken water heater, the stresses of grading papers, a recent Lily headline reading “My Mind Will Not Turn Off: This Is How I Experience Anxiety.”

This book is a representation of what it means to internalize everything. Using “the fact that” as a constant refrain brings, front and center, the current debate on truth and objectivity. But perhaps this structure demonstrates the difficulty of objectively analyzing information after we have so fully consumed it. Internalized information is personal and protected as such.

Ellmann has re-created information overload, but she has not done so haphazardly. Woven within these lengthy, panicked segments are shorter, beautifully written passages, detailing the life of the lioness. The narrator’s life parallels the lioness’s, as both navigate mates, motherhood, and environmental changes. The lioness lives in a world where “each mountain lion is part of a continuum, and privy to everything good and bad that happens to other mountain lions.” As our world invades theirs, so this fact becomes our own; narrator and reader come to understand that we are “linked to the pleasures, pains, and drama, the leap and recoil and lonely deaths of others. All living things are.”

Ultimately, the two mothers’ stories will converge as both come to inhabit a world marred by violence and spectacle. Yet both find an aftermath rich in love and connection, reminding us that even in a world of random events and infinite facts, meaning is abundant.

Mary E. Adams

University of Louisiana Monroe