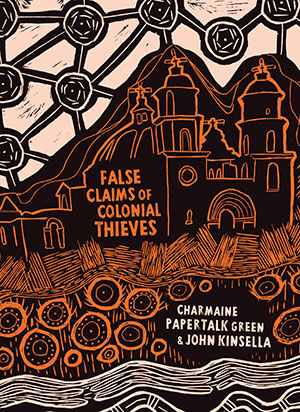

False Claims of Colonial Thieves by Charmaine Papertalk Green & John Kinsella

Broome, Australia. Magabala Books. 2018. 149 pages.

Broome, Australia. Magabala Books. 2018. 149 pages.

If poets are compelled toward cultivating voice, then, logically enough, to what ends? In his recent monograph, Polysituatedness: A Poetics of Displacement (2017), John Kinsella, one of Australia’s foremost politically engaged poets, asserts that poetry “is so often less about ‘art’ and more about ‘activism’” and that within this reckoning, he remains “interested in the poem’s potential for resistance, not its compliance with a status quo.”

False Claims of Colonial Thieves is a book that fearlessly pushes back against discourses of “Australia,” and these poems read that “country of milk and money” as a theater of long-standing epistemic violence. Herein, “[w]ho are the real rulers?” these poems demand to know. Co-written by Kinsella and Charmaine Papertalk Green, a member of the Yamaji Nation of Western Australia, these texts actively interrogate space—mostly Mullewa (population 425), a mining and farming town with a somewhat famous church—and cast critical light across that town’s “injustices, cultural cruelty, cultural genocide / And the cultural pain that is left behind.”

In his seminal survey of how imperial power is kept in place in postcolonial spaces, Edward Said asserts in Orientalism that there is “nothing mysterious or natural about authority . . . it has status, it establishes canons of taste and value.” Papertalk Green shows Mullewa’s century-old church mindlessly stamping ideological sovereignty on space that is historically a campsite for indigenous people; across Western Australia, these “stone piles cry out for attention”: “Whilst our Yamaji culture and history is still / Not celebrated or appreciated for its place on the land / How can over 50,000 yrs mean nothing?”

Amid the symbolic, ritual, architectonic performances of power in these texts, both poets regularly address one another directly, and in “Respect” Kinsella makes a thrilling disavowal: “Any rights I have over words I cede to you.” Here is a poet who actively creates space for another and, in so doing, interrogates his own position. Kinsella perhaps wishes more Australian poets would demonstrate similar measures of respectfulness, and he remains deeply sensitized to how hegemonies wield power to enforce acquiescence and complicity. His response? We must transgress: “The state deployed its shock troops who watched on as poems were yelled / at them, their commander marshalling attitude, saying: how can we / shut this one up? Poets of the world, take notice. They will close / you down the moment you break free of your anthologies, / your safety in pages of literary journals, the comforts / of award nights.”

Within these patrolled domains, it seems a poet’s work lies far beyond mere style. Kinsella and Papertalk Green demonstrate how to speak back relentlessly to those instruments of power that discursively fog and irradiate a land of “invisible victims.” Rather than remaining blinded by privilege and gently lyricizing, these poets undertake a fervidly necessary political intervention. Through books like False Claims of Colonial Thieves, “Australia” might one day entail more than a Terra nullius (qua quarry) in which dominant narratives shield a history of unspoken genocides.

Dan Disney

Sogang University, Seoul