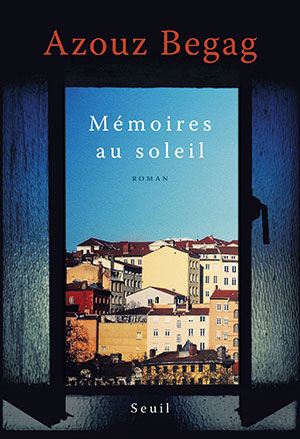

Mémoires au soleil by Azouz Begag

Paris. Seuil. 2018. 184 pages.

Paris. Seuil. 2018. 184 pages.

Ever since Le Gone du Chaâba (1986), Azouz Begag’s novels have been autobiographical, exploring his background as the child of impoverished Algerian immigrants in Lyon, France. Begag went on to become an economist, a novelist, and, from 2005 to 2007, a government minister. This novel is centered on his relationship with his elderly father, who is suffering from “la maladie d’Ali Zaïmeur.” This apparently flippant reference to Alzheimer’s disease is an indication of the tone of the narrative, which alternates between pathos and bemusement.

The plot is extremely simple: the narrator must find his father, who has once again wandered off on foot, apparently seeking to return to the home of his youth in Algeria. He will finally find his confused father at the ironically named “Café du Soleil,” where other retired immigrant workers from North Africa—who are known as the Chibanis—gather to pass the time and occasionally tell stories about the old days. The narrator spends the rest of a rainy day at the rundown café, observing the interactions between the aged working-class Chibanis while trying to reconnect emotionally with his ailing father.

Begag intersperses the narrative with flashbacks to his own disappointing trip to Algeria, in search of his roots, to his attempts at reconstructing his family history, which includes a grandfather who fought and died for France during World War I. At the café, a sort of suspension of time and place occurs, as the narrator offers brief glimpses of the lives of the Chibanis. The differences in terms of social class and generations are especially highlighted by the anecdotes about his father, the illiterate construction worker who struggled to provide for his children and who encouraged them to excel at school. Begag, who eventually obtained a doctorate in economics, describes his attitude toward learning as an attempt at “revenge” against his father’s extremely hard lot in life, against the destiny of failure that could have been his as a result of social determinism.

Toward the end of the narrative, he asks or prays for a reversal of his father’s grim medical destiny, for a miraculous cure that would restore his failing health and bring back his lost memories, perhaps through the use of “un eCloud, un eNuage.” The droll wistfulness of a cybernetic metaphor is typical of Begag’s treatment of what is ultimately a somber narrative. This moving elegy for his father is told with a light touch.

Edward Ousselin

Western Washington University