Poems as Lyrics: Poemas musicalizados in Uruguay

Uruguay has a long tradition of poetry set to music, “poemas musicalizados.” Although Uruguay is a small country, just 3.3 million people, it has always been full of both music and poets. The biographies of most important Uruguayan poets include a list of poems set to music by the musicians of their day. For example, the poems of Washington Benavides (1930–2017) were set to music by Alfredo Zitarrosa (1936–1989), Eduardo Darnauchans (1953–2007), and Daniel Viglietti (1939–2017).

Uruguay is also a country with a long tradition of poetry by women, starting with such poets as Delmira Agustini (1886–1914) and Juana de Ibarbourou (1892–1979), continuing through the two poets featured here today, Circe Maia (b. 1932) and Tatiana Oroño (b. 1947), and down to the present. I translated Circe Maia’s work for El puente invisible / The Invisible Bridge: Selected Poems of Circe Maia (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015) and so became aware of her “Por detrás de mi voz,” which was set to music in 1978 by Daniel Viglietti and became famous as the song “Otra voz canta.” It became an anthem and rallying cry for a generation fighting against military dictatorships in South America.

Behind My Voice

Behind my voice

—listen, listen—

another voice sings.

It comes from behind, from far.

It comes from the buried

mouths and it sings.

They say they are not dead

—listen to them, listen to them—

while the voice rises

remembers them and sings.

Listen, listen:

another voice sings.

They say they live now

in your eyes,

sustain them with your eyes,

with your words.

So that they are not lost.

So that they do not fall.

They are not only memory,

they are open to life

open wide.

Listen, listen:

another voice sings.

Por detrás de mi voz

Por detrás de mi voz

—escucha, escucha—

otra voz canta.

Viene de atrás, de lejos

viene de sepultadas

bocas y canta.

Dicen que no están muertos

—escúchalos, escucha—

mientras se alza la voz

que los recuerda y canta.

Escucha, escucha:

otra voz canta.

Dicen que ahora viven

en tu mirada.

Sostenlos con tus ojos

con tus palabras.

Que no se pierdan.

Que no se caigan.

No son sólo memoria

son vida abierta

abierta y ancha.

Escucha, escucha:

otra voz canta.

Daniel Viglietti, who died last year, was sometimes called the Bob Dylan of South America, but to me he was more its Pete Seeger, someone who spent his long musical life mentoring younger musicians. Sometimes he performed “Otra voz canta” with a recitation of Mario Benedetti’s poem “Desaparecidos,” about people who had been “disappeared” by the dictatorship. Here is a powerful performance featuring Viglietti and Benedetti:

Uruguayan musicians continue to set poetry to music. The songwriter Andrés Stagnaro recently recorded Juana. Marosa. Delmira. using the words of Juana de Ibarbourou, Delmira Agustini, and Marosa di Giorgio (1932–2004), whose collected poetry, I Remember Nightfall, was recently published by Ugly Duckling Presse in a wonderful translation by Jeannine Pitas. Tatiana Oroño, another Uruguayan poet I have been lucky enough to translate, has had her poetry set to music by the guitarist Daniel Petruchelli.

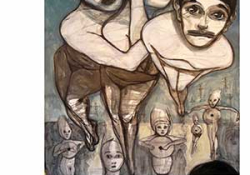

In May, I was in the audience with Tatiana at the Museo Gurvich in Montevideo, Uruguay, to hear him perform her poems.

Here is the title song “Elogio del camino” with my translation of the poem that forms its lyrics. With the Spanish words in front of you, you can see the parts Petruchelli repeats for emphasis, turning a short poem into a longer song.

Elegy for the Road

I ask where the things go that did not arrive at their destination. The majority of things. The largest inventory in the world. Where are they going to end up, the things that do not end up anywhere. Those that die before their time, those that have no remedy. I ask where do they go.

Poetry is the place where the things go that have no solution. To find it.

Elogio del camino

Pregunto adónde van las cosas que no llegaron a destino. La mayoría de las cosas. El inventario mayor del mundo. Adónde van a parar las cosas que no van a parar a ningún lado. Las que se malogran, las que no tienen remedio. Pregunto adónde van.

La poesía es el lugar adonde van las cosas que no tienen solución. A buscarla.

Madison, Wisconsin