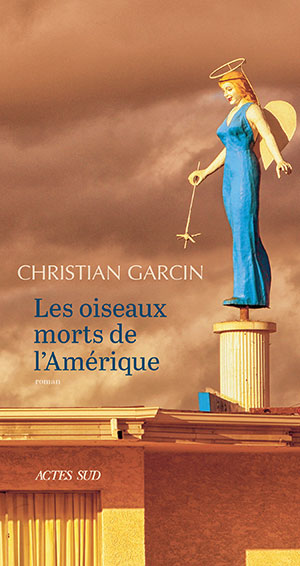

Les oiseaux morts de l’Amérique by Christian Garcin

Arles. Actes Sud. 2018. 221 pages.

Arles. Actes Sud. 2018. 221 pages.

Christian Garcin’s new novel puts individuals on stage who are rarely given voice in contemporary fiction. Hoyt Stapleton, Matthew McMulligan, and Steven Myers are homeless, and they live in a storm drain in Las Vegas, at some remove from the bright lights and ostentation of the Strip. All three are war veterans: Vietnam in Hoyt’s case, Iraq in the case of the other two. Among the three, Christian Garcin draws his focus most closely upon Hoyt. Born in 1944 to a teenaged single mother, he may have been fathered by Neal Cassady (a datum of which Hoyt himself is ignorant). Seventy-some years old in the narrative “now” of the novel, Hoyt is insatiably curious by nature, a curiosity he has nourished by reading any cast-off books that come to hand, from treatises in astrophysics to works of popular science and science fiction. He has trained himself to travel in the future and to ponder the various realities the future holds.

But when he begins to travel in the past, visiting the house where he lived as a six-year-old with his mother, Isadora, he is troubled by the things that he had failed to notice at the time, things that seem glaringly obvious to him now. Under the benevolent gaze of the Blue Angel statue in Las Vegas, Hoyt reflects upon the intersections of time past, present, and future, upon coincidence and serendipity, appearance and reality. How can one possibly be and have been in the same world, in absolute psychic synchrony? Must one conclude that we merely invent our truths as we go along? We exist in a world where the real is properly unthinkable, Hoyt concludes—and on a day when dead birds rain down from the sky in the thousands, that notion is abundantly confirmed.

Christian Garcin limns those meditations with the lightest of strokes, inviting us to consider his character on the terms that Hoyt himself constructs, and to appreciate the breadth of the horizon he inhabits. The patience of Garcin’s narrative rhythm is pleasing, as is his respect for unconventional ways of parsing experience. Moreover, the unapologetically humanistic impulse that animates this novel from first page to last is most welcome in times like these, when such impulses seem to be especially embattled.

Warren Motte

University of Colorado Boulder