8 Questions for Barrack Zailaa Rima

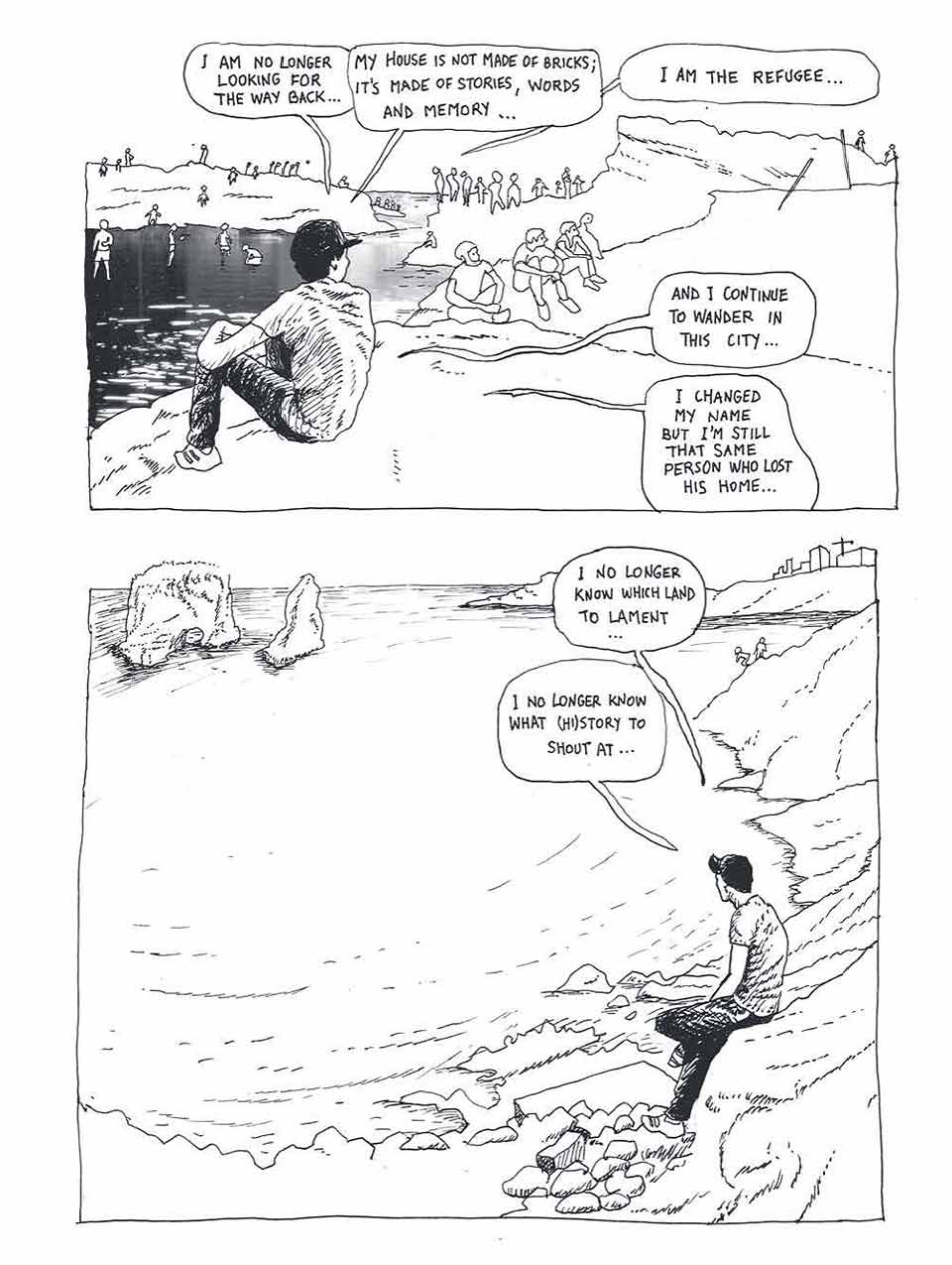

On September 17, 2024, Invisible Publishing will release Barrack Zailaa Rima’s graphic three-volume trilogy, Beirut, available in English for the first time in Carla Calargé and Alexandra Gueydan-Turek’s translation. Each volume retraces a visit Rima made to the Lebanese capital while also bearing witness to events unfolding in Beirut.

Q

The translators’ introductory essay, “Reframing Beirut’s Visual Archive: Barrack Zailaa Rima’s Beirut,” provides great context for the trilogy, which they describe as straddling the line between nonfiction narrative and magical realist fiction. Can you talk a bit about genre?

A

Thank you for asking this question. It’s my favorite. The distinction between documentary and fiction does not suit me. In a documentary story, there are always choices, frames, selection, and therefore a subjective part. In fiction, we project ourselves into the characters and the story, consciously or not, and we always tell very real facets of ourselves and the world. I obviously don’t want to make this a dogma, nor pretend that this is the case for everyone. But as far as I am concerned, I am attentive to the fluidity between genres and the possible paths in one direction or the other.

Q

Calargé and Gueydan-Turek also write about how your graphic alter ego acts much like a flâneur. I see this throughout the trilogy, in which the characters are constantly in motion. Has your relationship to Beirut been formed through walking its streets? Are you a flâneuse?

A

Yes, I am a flâneuse for sure! Either in Beirut, Brussels, or any other place. I used to go to Beirut quite often and spent a lot of time walking through its streets without a specific direction or goal, looking to architecture and people, hunting in secondhand booksellers’ bins, climbing abandoned and forbidden spaces, digging literally in the rubble of old buildings, etc. Being a native of Tripoli, I’ve never lived in Beirut (or only for a few months). This is how my relationship to Beirut has been formed.

Q

Why did you choose to create the trilogy exclusively in black and white?

A

I don’t feel it’s a choice; it’s intuitive. I prefer black and white (I would add “and gray”) in general, not only for the trilogy. I feel it much more as my language than color, and it was always the case since I started with comics. I like to refer to a famous quote by Orson Welles, who was asked why he prefers to shoot in black and white. Among several things in his answer, he said: because “we have removed one element of reality” (meeting with cinema students at Cinémathèque Française, Paris, 1982).

Q

How would you describe your relationship with Beirut at this moment?

A

I dedicated a trilogy to it, twenty years of my life, dreams, hopes, and aspirations. It is pillaged, demolished, and devoured by monsters, emptied of its soul, its stories, and its memory . . . that’s it, this time, I have detached myself from this city. I don’t want to go there anymore, or draw it, or hear about it . . .

That’s what I really wish I could say. But I know that’s not true.

Beirut is pillaged, demolished, and devoured by monsters, emptied of its soul, its stories, and its memory.

Q

What culture offerings or trends are you most interested in (or concerned about)?

A

I am passionate about Brechtian theater, particularly contemporary forms of engaged theater and performances, which draw on documents and history.

Q

Who are some graphic novelists that deserve more attention?

A

I think of Deena Mohamed, a young Egyptian artist. Her graphic novel Shubeik Lubeik has just been translated and published in English (2023). She is an Eisner Prize nominee. Also Joseph Kai, a queer Lebanese artist (Restless, see below).

Q

Are there other books, available in English, that grapple with Beirut’s recent history that you would recommend?

A

Many of the books I would recommend about Beirut are unfortunately not available in English (or am I wrong?). Among them:

(1) the novel Fou de Beyrouth, written in French by Lebanese writer Sélim Nassib;

(2) the graphic novel Madina Moujawira lil Ard (could be translated into “A city close to the earth”), written in Arabic and drawn by Lebanese artist Jorj Abi Mhaya; and

(3) the graphic novel Beirut Bloody Beirut, written in French and drawn by Lebanese artist Tracy Chahwan

Otherwise, available in English:

(1) the graphic novel Restless, by Joseph Kai (Street Noise Books, 2023);

(2) the graphic novel Beirut Won’t Cry, by Mazen Kerbaj (Fantagraphics, 2017);

(3) the graphic novel I Remember Beirut, by Zeina Abirached (Graphic Universe, 2014); and

(4) the novel Memory for Forgetfulness, by Mahmoud Darwish (University of California Press, 2013)

Q

What are you watching and listening to these days?

A

I watch the world drowning deeper and deeper in fascism and listen to the voices screaming: “When will the pain stop?”

I watch the world drowning deeper and deeper in fascism and listen to the voices screaming: “When will the pain stop?”

Editorial note: Read an excerpt from Deena Mohamed’s Shubeik Lubeik from the January 2023 issue of WLT.

A graphic novelist and filmmaker, Barrack Zailaa Rima is the author of several graphic novels, weekly sections, and compelling works of comics journalism including Le conteur du Caire, De Brusselmansen, and Sociologia. Her latest graphic novel, Dans le taxi, published by Alifbata Editions, received the prestigious Mahmoud Kahil Award for the best graphic novel from the MENA region (Lebanon, 2022) and the Grenades Literary Prize (Belgium, 2022).

A graphic novelist and filmmaker, Barrack Zailaa Rima is the author of several graphic novels, weekly sections, and compelling works of comics journalism including Le conteur du Caire, De Brusselmansen, and Sociologia. Her latest graphic novel, Dans le taxi, published by Alifbata Editions, received the prestigious Mahmoud Kahil Award for the best graphic novel from the MENA region (Lebanon, 2022) and the Grenades Literary Prize (Belgium, 2022).