Translating Colette

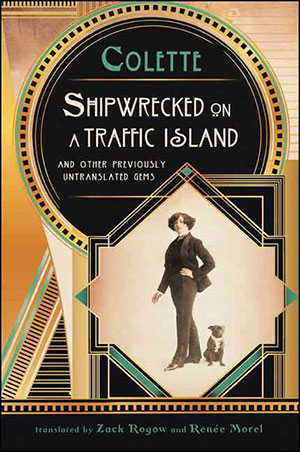

at the Théâtre des Mathurins, Paris, 1906.

Source: Little Penny Dreadful.

Sometimes half the battle in translation is locating the right texts. Shipwrecked on a Traffic Island and Other Previously Untranslated Gems by the French novelist and performer Colette (1873–1954) is an example of that sort of project.

I first stumbled across untranslated pieces by Colette when I was searching for a novel of hers to translate about ten years ago. I was using the book Colette: An Annotated Primary and Secondary Bibliography, meticulously compiled by Donna M. Norell, to try to find which full-length works of Colette’s had not been translated. The answer, to my chagrin, was none.

At the time, I ended up working on a previously translated novel that I particularly liked, Green Wheat (Le Blé en herbe), but I did discover from that bibliography and from pawing around in French magazines in the stacks of UC Berkeley’s Doe Library that there were numerous articles and short stories by Colette that had never made it into English. It reminds me of those games where you have to remember where a certain card was turned over: I made a mental note to come back to those shelves another time.

I did go back to those shelves when I was lucky enough to get a one-month residency at the Dora Maar House in Ménerbes, France, in 2010 (many thanks to the Brown Foundation Fellows Program at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston). I schlepped with me all the previously untranslated materials I could find by Colette. I had a suitcase full of short stories, reports from the home front in World War I, radio talks she’d never published, publicity pieces commissioned by the French perfume and fur industries, even an advice column she’d written for the French women’s magazine Marie Claire. In that one month, I read, selected, and did a rough first draft of about two hundred pages of my favorite material.

But finding these texts was only half the battle. When I got back to the States, I showed the translations to my friend Renée Morel, professor of French at City College of San Francisco, a native speaker, educated in old-school French academies. Renée has an encyclopedic knowledge of French language, culture, and literature, which she uses in the popular Café Musée series of lectures she gives in San Francisco. She agreed to team up with me to finish the translation. I relied on her to correct the numerous mistakes in my English versions, and to add her extensive knowledge of the Belle Époque and of France in those fascinating early decades of the twentieth century, so much like our own time in their experiments with gender roles and sexual freedom. What I didn’t anticipate was how many of my mistakes in English phrasing, grammar, and spelling Renée would correct. (Merci mille fois, Renée!)

Colette could command the most exalted, lyrical diction. She could also render the raunchiest language in authentic street slang.

In translating this book, we had to be aware of Colette’s many voices as a writer. Colette could command the most exalted, lyrical diction. She could also render the raunchiest language in authentic street slang. The piece translated here, “A Distinguished Connoisseur,” is an example of her more colloquial language.

Colette wrote this piece in 1909 when she making her living as an actor in popular music halls. She performed opposite the famous mime, Georges Wague, in the notorious drama Flesh. It was in this play that Colette became renowned for baring her breasts on stage, although that figures only peripherally in this memoir, which is about a claque. Traditionally, a claque was a group of people hired to sit in a theater audience and applaud loudly in order to stimulate the crowd to respond enthusiastically to the performance.

In this piece, first one, then the other character dominates a two-way conversation in which only one participant really speaks. Colette did an entire series of one-sided dialogues of this sort, a form particularly well suited to her ironic sense of humor. In this case, the ironies are doubled by the fact that the mime, Georges Wague, is at first the vocal member of the duet and then is so furious that he is speechless, until the final scene of this brief memoir.

In translating the slang, sometimes quite raw, we tried to be faithful to the spirit of the French. Slang is tricky, because it is often specific to a particular era, so it can easily sound anachronistic by being too contemporary, or not contemporary enough. We tried to walk that tightrope in our translation. Renée and I also devised a rhymed couplet in English to imitate the bathroom-wall graffiti quoted in this passage: Ici chacun fait un effort / Même les ouvriers du port! We tried to imitate, using English slang, the clipped diction, the frequent interjections, and the amusing metaphors that Colette so skillfully employs to re-create a conversation that jumps to life on the page.

In translating the slang, sometimes quite raw, we tried to be faithful to the spirit of the French. Slang is tricky, because it is often specific to a particular era, so it can easily sound anachronistic by being too contemporary, or not contemporary enough. We tried to walk that tightrope in our translation. Renée and I also devised a rhymed couplet in English to imitate the bathroom-wall graffiti quoted in this passage: Ici chacun fait un effort / Même les ouvriers du port! We tried to imitate, using English slang, the clipped diction, the frequent interjections, and the amusing metaphors that Colette so skillfully employs to re-create a conversation that jumps to life on the page.

A Distinguished Connoisseur

by Colette

I was appearing in Flesh, so I had to change trains in . . . let’s see, is it the second or third largest city in France? Doesn’t matter. The second, the third, and the fourth largest cities in France all have their “first-class establishment” where you can rake in “a nice take of three thousand five.” So you settle for the three thousand five. Now, I know that in almost all these first-class establishments—Kursaal-Casino, Casino-Kursaal, Eldorado, Eden-Concert—you will find, at the bottom of a staircase that smells of cabbage, a dressing room where you can smell the latrine; and the same slop pail, so small, but so dirty!

My friend Wague, the skilled mime, is putting on his costume in the dressing room next to mine, and with our doors open, we chat. Wague, an old trooper, tries to pump me up as best he can, because I’m as sad as a caged animal, out of my element in this new cage. Between us is born a nervous politeness, the fleeting effusiveness of exiles:

“So, Colette, did you see the marquee?”

“N . . . yes.”

“Not bad, huh?”

“Yeah.”

“It’s the color of red currant syrup. And letters this big! When they give me letters so damn big, I wish my name was Nebuchadnezzar, so it would be longer! The posters are nothing to sneeze at either, huh?”

“Yeah.”

“And have you seen the toilets here?”

“No.”

“Not so fun. I don’t know how they managed it, but they’re worse than Toulon.”

“!!!”

“You can sigh all you want, but that’s how it is. You remember the ones in Toulon where somebody had written: Here you strain to leave your rocks / Even the guys who work on the docks. We had a really good laugh that day, didn’t we?”

“Yeah.”

“Y’know, the box office is pretty good here, today. I wouldn’t mind coming back to this one-horse town. What about you?”

“Yeah.”

“‘Yes,’ ‘No.’ You’re acting like you don’t give a flying f . . . , you know that? Lucky for you I’m here. Who else worries about the posters, the photos for the program, the train schedules, everything! It’s me, the lover boy, because, if it was up to you . . .”

“I know.”

“Like for the claque, if I wasn’t here . . . I talked to the head of the claque just now. Very refined. An intelligent guy, distinguished. He looks like an executive in some office. He’ll warm things up discreetly. He has tact. I spotted that right away. Listen, someone’s ringing.”

“Is it for us?”

“No, my mistake. First there’s the jumping dogs, then the number with the Chilean acrobats. We’re after that.”

* * *

Midnight. Same location, after the show. Flushed, nervous, wired by the dancing and the applause, I sing in my dressing room while I take off my makeup, and the inexplicable silence of my friend Wague, in the dressing room next to mine, is getting on my nerves. But his precise motivation, his clear expressions and gestures, his final suicide all went over well, as usual.

“Hey, Wague, what a house, huh?”

“—”

“How about that, pal—four curtain calls!”

“Uh huh.”

“That’s not enough for you? What did you take tonight? Let me get a word in edgewise, will you? What’s the matter?”

Wague’s face, ferocious, smeared with Vaseline and thinned-out ochre and blue, appears: “What’s the matter? You have the nerve to ask me what’s the matter?”

“Well . . . yeah!”

He burst out: “What’s the matter? The claque. Did you hear the claque?”

“No, but since the audience spontaneously . . .”

“They didn’t make a single peep, the claque. Did you see those guys, that line of pimps, idiots, nitwits, clods, just sitting up there like a shelf of cheeses? Did you see him, that old geezer?”

“The head of the claque? The man with the distinguished air? The one who looks like an executive?”

Wague shakes his shoulders frenetically: “Him? An executive? You want me to tell you what he looks like, with his hair plastered on his head? Like a rat who fell in sh-t! Anyway, I’m waiting for him right now, and we’ll see why his regiment of sausages didn’t march!”

My friend Wague didn’t have to wait long. The “executive” turned up, perky, imperious, and supremely distinguished.

“So, there you are!” Wague shouted.

“Yes, here I am,” conceded this superior man. “I imagine you’re pleased.”

“Pleased? Pleased? Are you f-ing kidding me? Who told your guys to sit on their hands right when the dance started, and then just when the dress is pulled off, and then right in the knife scene when the blood spurts out? Huh, who was it?”

The “executive,” with a hand in a worn-out kid glove, waves away these reproaches as if they were bothersome flies. His thick, old woman’s face grimaces, with all its pretentious folds. And as soon as he can get in a word, he defends himself, exasperated, but courteous: “Monsieur, monsieur, if you please! I have tact, and what’s more, I know my profession. What is a claque? Can you tell me what a claque is?”

“—”

“Then permit me, sir. The claque is a coarse tonic, intended for anemic numbers. It is a vulgar spice that seasons a hysterical dance, it’s . . .”

“It’s a f-ing waste of a gold louis!” Wague interrupts bitterly.

“Permit me, monsieur! This tonic, this spice, I lavish them on those who need it, do you understand? Those who need it! But artists such as yourself, monsieur, and madame! I would blush, as a man of tact who knows his profession, to underline, to bruise what you do. Do you know what you do? What you do is beautiful! And beauty can’t be bought, not for a louis, not for even one hundred francs, monsieur! I bow before beauty, but I never interfere with it!”

Translation from the French

By Zack Rogow & Renée Morel

Editorial note: Excerpted from Colette’s Shipwrecked on a Traffic Island and Other Previously Untranslated Gems, to be published by State University of New York Press in November 2014. Translation © 2014 by Zack Rogow and Renée Morel.

Colette (1873–1954) wrote many novels, including Gigi and Cheri, made into popular movies. She was also a prolific writer of memoirs, journalism, and essays and authored regular features for newspapers, magazines, and broadcast media.