Different Coin, Equal Sum: Translating the Kopilka Poetry of Witness and Antiwar Protest

The current wave of russophone poetry of witness and protest is written by and for people who are confronting a catastrophe. The poet may compose a poem—and readers and listeners may encounter it—while sitting in a bomb shelter in Ukraine, while under arrest in Russia, while leaving their home for fear of annihilation or detention, while trying to continue their life in a lull between attacks, or trying to build it anew in a foreign environment and amidst the challenges of a refugee’s existence. The Russian regime’s horrific war against Ukraine, and the Russian and Belarusian states’ catastrophic slide into full-blown totalitarianism, are fracturing the very foundations of the Russian language and russophone culture—just as they are shattering individual human lives. The russophone literary diaspora constitutes the Greek chorus of this tragedy, according to poet Julia Nemirovskaya. While this literature tries to offer psychological and practical support to those most directly affected by the disaster, it gives voice to the anguish of witnessing these events.

Since February 2022, the start of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine, I have lost count of the public and private online russophone poetry events I’ve attended or listened to afterward. The frequency of such virtual get-togethers, their emotional intensity, and the number and geographical diversity of their participants far surpasses anything I have experienced before. At times, participants from Ukraine have connected to these gatherings via cell phones from bomb shelters or from candlelit apartments in cities without electricity. This is poetry at one of its most life-giving and historically significant moments.

This is poetry at one of its most life-giving and historically significant moments.

This is also poetry under attack by military might in one place and by state repression in another. For instance, since 2022 it has been a criminal offense in Russia to call the war against Ukraine “war,” as opposed to using the official label: “Special Military Operation.” Masha Gessen’s May 2023 article in the New Yorker, “Art Is Now a Crime in Russia”—a summary of what is happening to opposition poets and artists—is accompanied by a photo of poet and theater director Zhenya Berkovich sitting in a cage in a Moscow court. As I write this essay in March 2024, Berkovich is still in detention.

Julia Nemirovskaya, a US-based Russian-language poet and author, was born in the USSR in 1962 and came of age in Moscow during the waning decades of the Soviet regime. Immediately after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, poets in Russia—some of them friends from Nemirovskaya’s days in Moscow’s poetry underground—were being persecuted or threatened with arrest for their participation in antiwar protests. Nemirovskaya realized that there was a need for a safe place to archive russophone poetry that bears witness to and protests the horrors of Russia’s war on the people of Ukraine, that speaks against the mutation of the Russian and Belarusian regimes into totalitarian states, that simply reflects with honesty the experiences of people living through the cataclysms of this historical moment. She started the Kopilka (“coin bank” in Russian), a project dedicated to collecting and preserving these texts. Ever since then she has continued expanding and curating the collection. The poet Zhenya Berkovich, mentioned above, is among the authors whose work is included in the collection.

The Kopilka project attracted an international group of volunteers who work on translating the poetry from Russian into other languages. A team of five Russian-to-English translators began their work on Kopilka texts in early 2022: Maria Bloshteyn (Canada), Andrei Burago (US), Richard Coombes (UK), Anna Krushelnitskaya (US), and Dmitri Manin (US). I joined the Kopilka volunteer team in 2023 along with two other translators, Josephine von Zitzewitz (UK) and Niles Watterson (US).

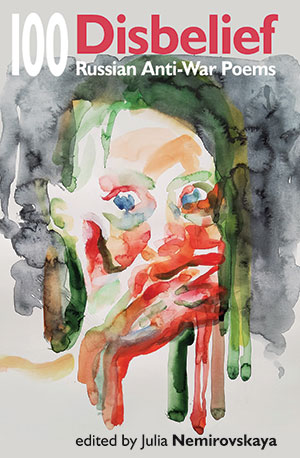

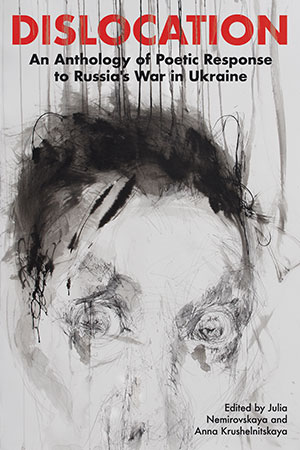

Disbelief, a bilingual Russian-English anthology of poems translated by the Kopilka team, was published in 2022 by Smokestack Books. Dislocation, a similar but much larger anthology, is slated for publication in 2024 by Indiana University’s Slavica Publishers. Krushelnitskaya served as Nemirovskaya’s co-editor for Dislocation in addition to her roles as a translator.

Disbelief, a bilingual Russian-English anthology of poems translated by the Kopilka team, was published in 2022 by Smokestack Books. Dislocation, a similar but much larger anthology, is slated for publication in 2024 by Indiana University’s Slavica Publishers. Krushelnitskaya served as Nemirovskaya’s co-editor for Dislocation in addition to her roles as a translator.

Before February 2022, I was writing poetry primarily in Russian and translating poetry primarily from English into Russian. After that date, I found myself struck mute in my first language. Translating poetry of witness from Russian into English is now my primary way of retaining a connection with the language of my childhood and, through it, with the world of my childhood. I examine my own motivations for translating this poetry in more detail elsewhere.

My experience with each poem and each poet is unique and specific to each such interaction. At the same time, I recognize in the work of the other Kopilka team members the same dual nature—both literary and deeply personal—that characterizes my own engagements with the texts and their authors.

After February 2022, I found myself struck mute in my first language.

When I started translating “Narnia,” a poem in Russian by the Ukrainian poet Dmitry Blizniuk, I emailed the author to ask him about the reason for the change in punctuation and capitalization that occurs in the middle of the poem. I did not hear back from him for several days. As I was waiting for a response, I was following with dread the news of Russian rocket attacks on Ukrainian cities, including Kharkiv, where Blizniuk lives. The opening lines of his poem were swirling in my head:

today let us go to sleep naked

like an ordinary husband and wife like lovers

take off all our clothes pants cardigans sweatpants parkas

stuffed

with passports medicines flash drives cash

keys credit cards cell phone chargers

let us take off our shoes and socks today let us

not fear that during the night a rocket will hit our home

but we will survive and have to run

through the starlit winter darkness into poland into narnia

At last, I did get an email from the poet. (Hurray! He is alive!) By way of responding to my question, he wrote: “‘Narnia’ was written in early March, under shelling and in a lull between bombings; I wrote it down the way it came to me, and then did not correct anything in order to maintain the effect of authenticity, the gloomy, sick reality, when you can be killed at any moment or an hour later, and this goes on and on. We just got the electricity back on, so I am responding promptly and quickly.”

At last, I did get an email from the poet. (Hurray! He is alive!) By way of responding to my question, he wrote: “‘Narnia’ was written in early March, under shelling and in a lull between bombings; I wrote it down the way it came to me, and then did not correct anything in order to maintain the effect of authenticity, the gloomy, sick reality, when you can be killed at any moment or an hour later, and this goes on and on. We just got the electricity back on, so I am responding promptly and quickly.”

Blizniuk’s note was such a succinct distillation of the context of his wartime poetry that I asked him for permission to translate this quote from his email and to use it to accompany my translation of “Narnia.”

*

I was also curious to know more about my fellow translators. Recently I interviewed Nemirovskaya and the five original members of the Russian-to-English translation team. I spoke online with each of them except Burago, who answered my questions via email.

These interviews were wide-ranging conversations, each with its own flow. However, a few topics were common to all of them. In this essay I focus on two of these throughlines. The first is the motivation for volunteering for the Kopilka. The second is rising to the challenge of translating poems, the impact of which is based on cultural knowledge and life experiences shared in common by the russophone poet and audience but which are unlikely to be familiar to the anglophone reader; examples of this shared context include texts that evoke vivid, sensory childhood memories and the folkloric roots of russophone culture. Another challenge of this type is posed by “inside jokes”—humor based not on the universal human predicament but on experiences that are common, significant, and specific to russophones.

When we were talking about what drives the Kopilka team to show such dedication to the project, Nemirovskaya began her remarks in a tone of slight irony but then quickly abandoned it and allowed intense emotion to shine through:

Whatever we are doing, we are doing it—first of all—for ourselves, to stay sane. Very selfish.

But another reason is … what the translator does with the poem is important for the poet, the author. This is a hard, very difficult, and painful time for the people whose language is Russian, people from former USSR republics, or from the diaspora. They feel that their work is validated somehow [by the work of the translator]. They feel that they belong to a group. … The poets benefit from that. And translators do too, I hope, because they also get the peace of mind that comes from doing something for the sake of Ukrainian victory and, eventually, peace.

I feel that there is a more abstract, maybe less palpable, but also very important goal. I tell myself: keep going, keep this Russian-language poetry working. There is an attempt by a fascist and illegitimate government—which is conducting an illegitimate war—to appropriate the language and the culture. … I’m not ready to give up the language and the culture to Putin and his cronies. So, what I’m doing, maybe sometimes unconsciously, is to be a witness to the Russian language, literature, and culture staying afloat.

“There is an attempt by a fascist and illegitimate government to appropriate the Russian language and the culture.”—Julia Nemirovskaya

Nemirovskaya responded with enthusiasm to my question about the allusions to childhood-related or folkloric texts, and the context-specific humor of the Kopilka poetry:

It’s something that really interests me, and as a poet, too, because I feel like there is a way to somehow mitigate the pain by transferring the topic of, for example, war atrocities into a pseudo-folk or pseudo-children’s poetry piece. And all those allusions, like any allusions or parallels in literature, create perspective for the poem and give it a great stereo effect where one reverberates with the other. Like quotes, for example: they immediately reach out to another sphere, to another era, to another set of voices. … It becomes an orchestra rather than a lonely voice or one lonely musical instrument.

One of the ways the Kopilka poetry achieves the “stereo effect”—and distills the intensity and complexity of the feelings with which the poets respond to the shattering of the foundations of russophone culture—is through allusions to early childhood impressions and experiences. Many of the Kopilka poems employ verbal means to activate preverbal memories. For instance, they evoke lullabies and other songs that have been the auditory backdrop of the early childhoods of several generations of russophone poets and their readers.

An example of a lullaby-based poem is Vanechka’s “Sleep, My Boy,” translated by Richard Coombes and slated for publication in Dislocation. It is sung by a mother, a personification of Mother Russia. Although it uses the tropes (prosody, rhyme, diminutives) of a text created for a baby, it turns out to be addressed not to a child but to a killed soldier:

Sleep, my boy, my little laddie,

Splendidly and sound.

Rifle stock and old kit baggie,

Piled up on the ground.

Safety helmet, flakkie jacket

Booties, left and right,

Sweetly listen to fairy stories

In mother earth tonight.

The lullaby concludes by using the same sweet intonation to prophesy many more such deaths:

Boyish head to boyish head,

Packed in by the score.

Nightingales all lying dead –

And there’ll be plenty more.

Rounded earth in woodland, marking

The places where you fall.

Sleep you tight, my little darling.

Don’t wake up at all.

Coombes stated his purpose in working on the Kopilka translations with eloquent simplicity: “My interest is in finding people who deserve to be heard, but are only currently being heard in Russian, and getting them heard in English.” In talking about translating “Sleep, My Boy,” Coombes focuses on verifying and transmitting the emotional impact of the original:

I’ve done quite a few of Vanechka because I became attracted to her wild and dangerous style. When I read that lullaby, I was absolutely horrified. But I thought it was brilliant, and that it had to be part of what I was doing.

So, I translated it. And I thought I might have got it completely wrong. I sent it to a friend [a native Russian speaker] who’s extremely well-read in both Russian and English. And she said: “Richard, this absolutely makes my skin crawl.” … And then I had doubts ten minutes after I’d closed the chat. I sent it to another friend of mine, a successful Russian author. She said: “Oh Richard, this is amazing, отличный приём [excellent device].” She explained what was going on. And I said, “That’s what I thought.” And then I panicked again and sent it to somebody else. In the end, they all lined up and said: “Richard, this is just what you think it is.” But I had real doubt over it because it was so horrific.

I chose words germane to English lullabies. They sound awful in this context, but I used them deliberately. … I thought we don’t need this sugared at all; we need it to be as horrible as it really is.

“I’ve done quite a few of Vanechka’s poems because I became attracted to her wild and dangerous style. When I read that lullaby, I was absolutely horrified.”—Richard Coombes

In addition to lullabies, the Kopilka poems evoke early childhood by songs and chants associated with games, such as pregame counting-out rhymes, the sort of rhythmic ditties chanted by preschool children to assign roles in games. These texts tap into vividly embodied memories: muscles tensing and hearts racing as children get ready to run or hide. An example is “Counting Out,” by Irina Mashinski, translated by Maria Bloshteyn. (The translation appeared in the ninth issue of ROAR: Resistance and Opposition Arts Review, an online project.) The English version starts with:

Black shoe, black shoe, he is coming at you –

looking kind of shady but acting grand,

stepping from the fog in a gray suit,

brandishing a switchblade in his hand.

Bloshteyn spoke about what draws her to the Kopilka poetry translation with great animation; I felt that she was about to reach out of the screen and “tag” me in a game:

You reach for something that you can’t express yourself. You reach for someone who has said it for you. This is what we found; this is what Julia [Nemirovskaya] has been saying about this poetry. This is a language to express the inexpressible. There is something horrific a newspaper doesn’t express. It gives you the facts, but it doesn’t really do it for most of us. … We offer something that expresses the inexpressible. Something that grabs you in a way that ordinary texts do not, something that gives you an insight, that puts you in there. Poetry is experiential.

“We offer something that expresses the inexpressible.”—Maria Bloshteyn

Bloshteyn illustrated this point by telling me about translating “Counting Out”:

I started looking at English nursery rhymes and counting-out rhymes, and nothing was working. I looked at Mother Goose, and nothing was working. And then one of my kids came up with a ‘black shoe, black shoe’ counting-out rhyme. I thought it was perfect. It’s not exactly what Irina is doing in the poem; it’s obviously not the one she’s using. She is using the famous one: ‘Вышел месяц из тумана, Вынул ножик из кармана, Буду резать, буду бить, Всё равно, кому водить’ [Crescent moon slipped out of clouds, / Had a blade, and pulled it out. / I will slash, and I will hit, / Doesn’t matter who is “it”]. I’ve heard it as a kid from my mom, from her childhood. I used this English equivalent because it was so ominous. This black shoe is coming to get you.

So, I think that’s how you do it. You try to find something that’s culturally parallel, that will get the reader into the same kind of experience that russophone readers are experiencing when they’re reading the poem.

*

In addition to the songs and chants associated specifically with early childhood, the Kopilka poetry frequently refers to songs that formed the soundtrack of life in the Soviet Union for people of all ages. There were two broad categories of such songs. One consisted of state-approved music that poured from the ubiquitous radios day in and day out. The other constituted the musical underground: these songs were transmitted in clandestine gatherings, sung to guitars in kitchens and around campfires. The underground genres included so-called “bard” songs—sophisticated poetry, serious or humorous, used as lyrics—and “urban romances,” folksy, lowbrow, sentimental ballads. While the post-Soviet generations have access to a far greater variety of music, the old classics are still deeply embedded in the culture; they are still instantly recognizable and laden with emotional significance.

Yulia Fridman’s “The Radio Is Spewing Crash and Clangor”—translated by Dmitri Manin and slated for publication in Dislocation—alludes to well-known examples of both the sanctioned and the underground songs from the Soviet era. The first stanza contains a direct quote from a bard song, the “Immortal Kuz’min,” created and performed by the dissident poet Alexander Galich and retransmitted in samizdat recordings or in clandestine performances by countless fans, despite the risk of persecution.

The radio is spewing crash and clangor,

The loudspeakers are thrashing on their stand.

“Citizens, the Motherland’s in danger,

Our tanks rolling through our neighbors’ land!”

Fridman’s first stanza evokes the bitterness and urgency of the text written by Galich in 1968, when the Soviet regime sent its tanks to crush the “Prague Spring.” Galich satirized the Soviet propaganda attempts to paint that action as a necessary defensive maneuver. At the same time, he called attention to the Motherland’s moral peril created by its own aggression. By quoting the Galich song, Fridman draws a parallel between the events of 1968 and today’s invasion of Ukraine.

Fridman’s piece ends with an indirect, but unmistakable, reference to a beautiful, pensive, and melancholy song based on a poem by Rasul Gamzatov about the World War II dead. In Gamzatov’s text, the soldiers who had not returned from the blood-soaked fields turned into white cranes. They kept flying across the sky, calling out to the living. This song, played endlessly on Soviet radio starting in the late 1960s, was imprinted on everyone’s hearing. The images of flying cranes were used in monuments to the war dead. In Fridman’s poem, the soldiers who fell in battles defending the Soviet Union against the Nazis now rise up to defend Ukraine against the Russian invasion.

Those who stayed on blood-soaked fields forever

Eighty years ago, now fill the skies,

Tactical white hornets, slice the air

Coming for our tanks with mournful cries.

Manin told me that his interest in translating poetry originally (in the prewar era) stemmed from his interest in linguistics. He added, his face breaking into a grin:

There is no better reason to translate than just pure fun. I’m always driven by things that are interesting to me, that are play. … Fun is a kind of internal motivation. But then there is external motivation, which is sharing. It is both sharing a poem that I like with the reader, but also sharing in creating it with the author. That sharing part, of course, became much more important in Disbelief, Dislocation, and the Kopilka. It is not just because I want to share something, but because there are real-world consequences of that.

In our discussion about translating poems that are based on cultural references intimately woven into the psyche of the writers and readers of the original, but unfamiliar to the English-language reader, Manin focused on the importance of the poet’s unique voice:

This is a very thorny topic, and I don’t have a universal answer—other than that I think even in these cases, the principle of hearing the voice is still the basis for everything else. To me, the sine qua non of poetic translation is to reproduce—like a radio reproduces, like a gramophone reproduces—the voice of the poet. Speaking different words in a different language, but it’s still the same voice. I don’t even know how to define it. It’s something that purely comes through the ear. The poet speaks with a different voice when he or she is singing someone else’s song or quoting a childhood ditty. This modulation of the tone needs to be reproduced. It can hint to the reader that something is going on there.

“To me, the sine qua non of poetic translation is to reproduce the voice of the poet.”—Dmitri Manin

Manin’s translation of Fridman’s poem illustrates his point about staying true to the author’s voice, including the ways that voice is modulated to indicate allusions to different texts. The “crash and clangor” of Galich’s sarcasm give way to the elevated vocabulary and more lilting sound that convey Gamzatov’s sadness: “stayed on blood-soaked fields forever,” “mournful cries.”

*

The Kopilka poetry frequently evokes not only the earliest and most vivid memories of its readers but also the deepest memories of the culture itself—its folkloric roots. For instance, “A Folk Song,” by Dana Sideros, translated by Andrei Burago and slated for publication in Dislocation, follows the form of a traditional wedding song in which the guests praise the opulence of the celebration and conclude by showering the newlyweds with good wishes. In this song genre, the bride and groom are sometimes allegorically represented by lovely animals, such as doves. In the Sideros poem, the newlyweds are mice; their wedding is taking place inside a corpse torn apart by an explosion and left in a field: “we will chant on rib cage pews … and like flowers on the ground / stripes of cloth are spread all round.” The wassailing concludes with a grim twist:

fill your cup and drink it up try the green crabapples

pouring o’er the married couple

ashes ashes ashes

Another example of a poem with folklore elements, also translated by Burago, is Alla Bossart’s piece published in Disbelief. This piece starts with a quote from the highly literary and widely known Mikhail Lermontov poem “Angel.” However, the rest of it is written in the genre of “urban romance”:

An angel was crossing the sky of midnight

His tiny wings went putt-putt.

Golden curled, swift and featherlight,

No business to think about.

He was coming to visit his native land

Which, in his life before,

He left, along with some fifty men,

And went to fight in a war.

This poem, both ironic and tragic, talks about the dead soldier, about his wife who leaves home for many years in a fruitless attempt to find his grave, and about his son who grows up to repeat his father’s fate.

Burago has several motivations for his Kopilka work. He wrote:

I do believe that translating antiwar poetry brings victory and peace closer. … We need to tell the world about this war, and poetry is a very powerful medium.

For me, poetry is part of language. If I want to discuss the war with someone anglophone, being able to share my favorite poetry pieces with them feels essential.

Overall, I think that every exercise in translation proves again and again that gaps between languages, cultures, and peoples can always be bridged. I am an idealist after all, aren’t I?

“Every exercise in translation proves again and again that gaps between languages, cultures, and peoples can always be bridged.”—Andrei Burago

Burago responded to my questions about how he works with the folkloric and humorous elements:

What I try to do is ask myself, “What is the purpose of this reference? What is the author trying to accomplish?” For example, in Bossart’s “Angel,” even though the first line is a direct quote from Lermontov, the actual poem differs from Lermontov’s in every possible way. … The second line, a humorous quote from a song from a popular movie, is so out of place after a line from Lermontov that it makes you smile. I changed this “бяк-бяк” to “putt-putt.” The reference was lost, unfortunately; I could not find a similar quote from an English-language song or movie. Was “putt-putt” a good substitute? I am not sure. When I thought of an angel crossing the sky with a motorcycle sound, beating wings that are too small for him, it did make me smile. (Obviously, the translation was done before Shahed drones made this mental picture a lot less amusing.)

Similarly, the Sideros poem is full of dark humor. I think of it as a fable, actually, where people’s lives are depicted as the lives of animals and ridiculed this way. (How do you like “howling” on pews during a wedding ceremony? “Poppy dew” for booze or “wagtails” that are heading for the south?) Of course, these simple, happy animal lives are in fact built on the bones of a dead, unburied soldier.

*

The mix of dark humor and tragedy in these two texts translated by Burago exemplifies yet another way that the Kopilka poetry establishes an immediate, emotionally charged connection with its readers. Many of the poems are filled with bitter, throat-scorching laughter in reaction to something that is simultaneously horrific and utterly absurd. It is laughter that “sounds like screaming” (according to a poem by Sandzhar Yanyshev, translated by Dmitri Manin).

Much of the humor of the Kopilka poetry is challenging to translate because it is built not on some universal human predicament but on the specifics of the current situation. These are viscerally familiar to the russophone audience but may be unfamiliar or abstract from the point of view of the anglophone reader.

One type of absurdity satirized by the Kopilka poetry is the sort of claim the Russian regime uses to justify its aggression. Yulia Fridman’s poem, translated by Maria Bloshteyn, starts with a justification for the war that is a staple of Russian propaganda. The rest of the poem spins off into a mad romp that nonetheless is not too far removed from some of the wilder conspiracy claims made by various prowar voices within Russia about the dangers posed by Ukraine and other societies outside of Russia’s borders. Bloshteyn’s translation conveys the fervent conviction with which proponents of such ideas put them forth:

When we had liberated Ukraine from the Nazis,

Poland from Martians, Finland from dog-headed men,

the Earth sprouted fragrant cocaine-smelling blossoms,

and our tankmen got high on their magical scent.

Lithuania became a hotbed for galactic snails

from Epsilon of Andromeda, that cold crimson star;

they hid among salad greens and other plants,

we bombed it flat – no choice but go that far.

The Kopilka poetry not only mocks this bacchanal of lies but also sets it side by side with the real tragedy of the war. For instance, “Fake News,” by Alexander Delfinov and translated by Anna Krushelnitskaya, opens with a collage of “fake news” of the type poured into and recirculated by the minds of the brainwashed populace. This toxic stream covers every topic, including everyday life, religion, and politics. It drowns out any reflection about what is actually happening within Russia and outside its borders. Here are a few illustrative quotes:

Got news for you: one chef – now, this one’s disgusting indeed:

He butchered a man to fry and serve him as steak!

…

A fake Jesus offers a fake salvation;

A fake Satan casts you to a fake tarnation.

…

And do tell me, why does the UN push its boundary eastward?

What? Not the UN? Same difference; they’re all Freemasons.

The poem concludes with a return to the reality of what Russia’s attacks are doing to their Ukrainian neighbors. It is so horrendous that admitting to it causes the language itself to fall apart and turn into incoherent babble:

But if you peek out of your personal info bubble,

Like out of a hatch of a tank that’s burning,

You’ll see the ground heave, blasted into rubble –

Or is it the still-living, the wounded, stirring?

…

You’ll see an air defense missile slink through the sky like a snake,

And then you might think that you, yourself, are truly fake,

And only death alone is the antithesis of the fake.

Fake-uh.

Ache-uh.

Kuh.

Uh.

Krushelnitskaya’s primary reason for working on the Kopilka translations is similar to Manin’s: “It is simply one of the things in this life that are existentially pleasing, or interesting, or fun for me to do.”

“Bridging the unbridgeable, huh? As a translator, I am a utilitarian.”—Anna Krushelnitskaya

She responded to my question about translating humor with a knowing chuckle. “Bridging the unbridgeable, huh?” Krushelnitskaya then articulated her overall approach: “As a translator, I am a utilitarian.” She alluded to a quote that came to Russian literature via the writings of Vasily Kapnist, an eighteenth-century Russian and Ukrainian poet and translator. Kapnist translated this quote from Jacques Delille, a French poet famous for his translation of Virgil’s Georgics. According to Kapnist, Delille defined translation as “repaying the author though not in the same coin, but with an equal sum.”

Krushelnitskaya illustrated her approach by walking me through a few of the steps she took to translate “Fake News.” “The first thing to know about this poem is that it’s a slam poem, and that it is to be delivered orally. It’s supposed to be phonetically sound—it’s not just letters on the page; it’s the sounds that you make.”

She went on to illustrate how she transmitted the folksy, warm tonality of how death is being addressed in one of the lines of the poem. The original uses the expressive suffixes of the Russian language: “Смертушка-соседушка, одолжи нам фейка!” [Death, dearest neighbor, lend us some fake]. But English does not offer the same tool for transmitting the emotional register of words. Krushelnitskya employed a semantic tool to convey the same tonality: “I’m introducing this ‘half-a-cup,’ and that immediately brings us the context of neighbors at each other’s door: ‘Death, my friend, I’ve come to borrow a half-a-cup of fake.’”

She discussed how she worked with the puns that abound in that poem. Here is what she said about one of her examples: “Let’s say I’m looking at ‘Нас тупила.’ On the one hand, ‘Наступила’—‘it arrived.’ On the other hand, ‘Нас тупила’—‘it’s dumbing us down.’ What to do with this, what to do?” Krushelnitskaya’s solution was to twist the name of a classic rock song, “The Dawning of the Age of Aquarius,” into “The Dumbing of the Age of the Fake.” She remarked, “It is a joke. It is not the same joke. We repaid him, not with the same coin, but with the same amount he wanted.”

*

The motivations that draw the “charter members” of Kopilka’s volunteer team to this work resonate with my own. I, too, am drawn to translation because I am fascinated by the concept of bridging gaps between languages. I, too, am motivated by the burst of joy I experience whenever I find a clever solution to a challenge. And I, too, find some relief from the feelings of grief and helplessness by sharing a poem that moves me, by being able to connect to and serve a poet who continues to create beautiful and powerful poetry even while facing horrific circumstances. Like my Kopilka colleagues, I hope that making this poetry available to anglophone audiences helps the cause of resistance to totalitarian aggression and supports the people who are standing up to barbarism.

I wish to add just one more point to this list of motivations. I observe the care with which each member of the Kopilka team treats both their own translations and the translations of their teammates. In the workshop-style email exchanges among us, a single line, a single word, is sometimes discussed for days until a translation conundrum is resolved. I sense how we support one another in our shared experiences and in our individual moments of joy and of loss. And I feel inspired by collaborating with the Kopilka translators and editors, by being part of this team.

Fairleigh Dickinson University

Author’s note: I gratefully acknowledge Professors Minna Zallman Proctor and Padma Viswanathan for their mentorship, and Bruce Esrig for editing my English-language texts.