Can Translation Enrich Our Mental Health?

Can translation make us mentally healthier? Can adding new words to the English language somehow increase the amount of positive emotions that we experience on earth?

Can translation make us mentally healthier? Can adding new words to the English language somehow increase the amount of positive emotions that we experience on earth?

This, in short, is the argument launched by happiness researcher Tim Lomas in his 2016 paper “Towards a positive cross-cultural lexicography: Enriching our emotional landscape through 216 ‘untranslatable’ words pertaining to well-being.” In this paper, he identifies and organizes some 216 terms from languages other than English that he believes can enrich our lived experience.

As Lomas puts it in the abstract, his paper has two aims: “First, it aims to provide a window onto cultural differences in constructions of well-being, thereby enriching our understanding of well-being. Second, a more ambitious aim is that this lexicon may help expand the emotional vocabulary of English speakers (and indeed speakers of all languages), and consequently enrich their experiences of well-being.”

In a 2019 TEDx talk, Lomas expanded on these sentiments. In part, he argued that the field of psychology overwhelmingly happens in the English language, so it runs the risk of leaving out so much that only occurs in languages other than English. Through the act of translation, he argues, we can add to the positive impacts of mental health interventions like psychotherapy. “Untranslatable words,” Lomas declares, “have the power to uplift and transform our reality.”

Since the original paper, Lomas has gone on to author further papers on the subject, create a website for the project, and publish three books: Translating Happiness: A Cross-Cultural Lexicon of Wellbeing, The Happiness Dictionary: Untranslatable Words from around the World to Help Us Lead a Richer Life, and Happiness: Found in Translation. He has even created a thematic guide to these words (which features many new words not found in the original paper).

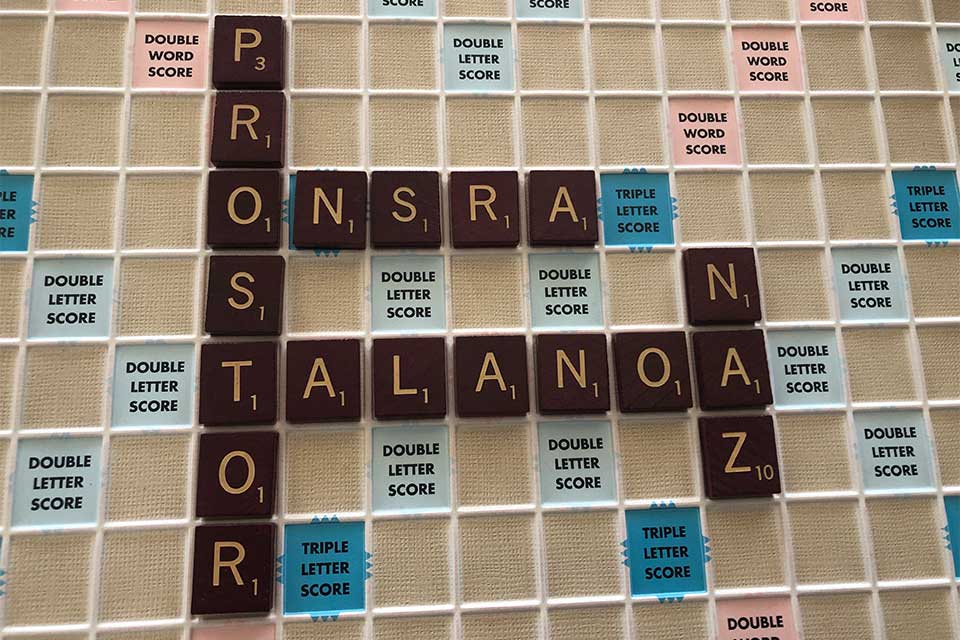

Whether or not you believe the claims about mental health and well-being, Lomas’s original paper and his subsequent work are a treasure trove of untranslatable words. For instance, just to name a few of them: there is the Polish kombinować, which “refers to working out an unusual solution to a complicated problem, and acquiring coveted skills or qualities in the process.” There’s the delightful Portuguese word desenrascanço, “to artfully disentangle oneself from a troublesome situation.” There’s the extremely relatable Fijian Hindi talanoa, which “describes the way apparently purposeless idle talk functions as a ‘social adhesive.’” Who doesn’t melt at onsra, which comes from the Boro language of India and means “to love for the last time”? And I just feel better hearing about the Urdu word naz (از ن), which is “the assurance and pride one can feel in knowing that the other’s love is unconditional and unshakable.” Lastly, there is the wonder in the Russian word prostor (простор), which “captures a sense of spaciousness, roaming free in limitless expanses, not only physically, but creatively and spiritually.”

Who doesn’t melt at onsra, which comes from the Boro language of India and means “to love for the last time”?

It is, of course, a lovely idea, that enriching our language can help us live better lives, but is there any substance to Lomas’s claims about what words can do for us? To begin, the field of psychotherapy is certainly no stranger to the idea that the words we use can very much impact our mental health—see, for instance, the research presented by the Dulwich Centre around the effectiveness of narrative therapy interventions. Such research presents evidence that practices like writing down our own narratives of trying experiences, creating poetry from conversations around bereavement, and changing the language of communication with spouses can all lead to improved mental health. Likewise, very widely practiced modalities like cognitive behavioral therapy often work on the level of utterances, helping clients to fine-tune language that helps them cope with difficult situations.

While there is much evidence for languaged-based therapeutic interventions, there is, unfortunately, no such research among Lomas’s prodigious output of academic papers. (Although, his papers do include a recent one on the cultural meaning of angels and UFOs.) In my own search, I was unable to find anything attempting to put his translation claims to the empirical test. So, Lomas’s theories, pleasing as they are, seem to remain untested and unproven.

Until the day that we get some kind of firm scientific analysis of Lomas’s ideas, interested readers can try it out for themselves and see what happens. Anyone can read Lomas’s papers and can integrate some of his untranslatable language into their own lives to see if it changes anything. And if you want to try integrating some of these words into a narrative therapy framework, you can use some of the exercises and prompts on this PositivePsychology page to get an idea of how to test-drive things. You can also look into Lomas’s many scholarly and popular articles for more thoughts on his ideas and more ways that you might make use of this language in your own life.

Oakland, California