Two Illustrated Bird Poems from Israel

A Note on the Illustrations

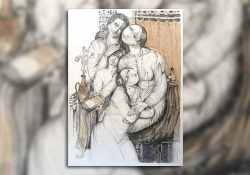

Diti Ronen: “I suddenly have this unexplained urge to send you for publication these two poems along with three images—out of hundreds—that were made by Isis Olivier, the granddaughter of Sir Laurence Olivier. Isis, an accomplished French artist, read my poem ‘littlebird’ in 2014, when it was presented in French at the Lodève Poetry Festival, France. Ever since, along with other projects, she continues to draw the moment of the falling of the bird, and we have already presented together four exhibitions, including readings. Surprisingly, the act of drawing the endless moment of the falling, inspired by the poem, is actually done with the help of dead birds that she finds on her way or at her doorstep, unexpectedly. The poem ‘Fifth Bird’ was written recently, right after she told me about a new bird that came to die at her doorstep” (email to Daniel Simon, August 24, 2016).

Isis Olivier: “After Diti invited me to do some artwork for her poem ‘littlebird,’ it took six months to find what I was looking for. On a frosty January morning, there it was: a dead song thrush. Diti was enthusiastic about the first charcoal and chalk drawings. I then spent months drawing and painting birds. When I felt that I had almost exhausted the subject, another bird would appear and then another, literally on my doorstep. From the dichotomy between hope and despair in Diti’s poem to that of life and death, the fallen birds have come to represent lost innocence, merging somehow with the flow of refugees into Europe and the images of their children drowning on our beaches.”

Fifth Bird

Fifth bird lands on your doorstep

To die at your feet.

Again you are called to open the sky

To send off your visual prayer

The image of the movement

Of an eternal moment.

Again you delve into the body of the poem.

I listen carefully, and write the letters

Of the simple present

Of our Life and of our Death

That return again and again

From Above and from Earth.

littlebird

Begin from above

slowly,

in a blue so light, so light

and wide and big and white

begin, with infinity

begin with the sky.

With the bird.

Look, she is taking off.

One bird, little. Look.

There she flies.

Big and open –

the entire sky is in front of her.

Begin with the bigness, yes, begin big,

from above, big,

begin with the all-seeing point of view

the innocent point of view

the point of view of God

who does not see the detail.

Were there other birds?

Was there a chirp?

There was, surely there was.

There, another bird, taking off.

Begin with the horizon.

Do you still see on it any wisp of smoke?

No, it is not dusk yet,

you cannot see a thing.

And the horizon is far and the sea is close

and the sun is in mid sky.

Now treetops peek out,

appearing.

Begin with the treetops.

They spread, ever green,

their fingers yearn for the tall,

the divine,

for God looking upon them, for

the bird.

Did the sun indeed shine?

And what was the shape of the cloud?

God, watching, did He notice the bird?

Begin with the tree. With the bough,

see how it hugs the trunk,

leaning on it, ever so trustingly.

It too is quiet. Slightly moved by the wind.

Cuddling itself softly

humming the sounds of its origins.

Have you noticed the nest?

Have you seen the nestling?

Begin with the tree.

With the tree next to it.

Remember the bird?

It descends here, to sit on a bough.

Begin with her.

No. Begin with her tree.

No. Begin with the tree next to her tree.

Begin with more trees.

Many trees.

A forest.

Now look. From above.

Can you see the forest clearing?

Look.

There are lager barracks there.

Begin with the barrack.

It does not matter which one,

they are all alike.

Begin with the tenth barrack.

Look, a handsome woman now leaves it.

Her walk is proud.

Did you draw her?

Draw her pretty, please,

Pretty, bald and proud.

Did you see?

Her round face, turned slender,

accentuating big, blue eyes.

She looks up.

Sees blue skies

sneaking between the treetops

that you drew, and the tip of a cloud

shaped like a longing.

She notices in detail.

Remembers scent and flavor,

color and sound of before.

Thinking spring.

Sees the bird

passing in front of her,

gliding, her wings spread open.

Begin, with the officer.

Draw him tall.

Accentuate his face, please.

It is squared. Draw his

Strong jaw, his chin

sticking out.

Now the hair: carefully done,

his hat hanging in sloppy elegance.

Have you seen his uniform?

The emblems on his sleeve?

Begin with the rifle.

The officer holds the rifle in his hands.

He stands by the barrack. The rifle in his hand.

Now he lifts his weapon,

aiming to the sky.

Pressing his cheek against the weapon

closing a non-aiming eye

and searching.

Draw him tall. And very straight.

He looks through the crosshair

up, he’s searching,

what shall he shoot now?

The bird now stands on a branch.

Draw him looking, draw the look.

He moves, turning to the woman.

Look. He

forgets his mark. His muscles relax.

Draw the gun descending, slipping down his arms.

Draw the firing position fading.

He looks at the woman.

Her walk so proud

dressed in a sack and a simple waistband.

He looks at the woman.

She does not see him,

walking forward, to the latrine,

her gaze fixed on the bird.

Draw him looking at the woman.

Looking at the train of her walk,

the ripples sent forth from her behind.

There, she has entered the latrine.

He once again lifts his weapon.

Determined. Indifferent to the ripples,

indifferent to the train of her behind.

Did you see? Once again, he presses his cheek,

and although it is spring in the world

and perhaps because of

the cold steel

he closes one eye.

Watch.

He aims, concentrates, aims,

and the bird, oh, the bird,

her exactly –

and shoots.

Did you draw it?

Could you draw her sinking?

There, here, so close,

right by, her body

like God landing softly,

unheard.

Begin with the woman.

She hears a shot.

One, and its echoing

knocking at her temples

thudding to the ends of the forest

and back. Was she hurt?

Draw the sound, the bang,

draw her anxiety.

Draw her leaving the latrine.

She walks. There, she walks, she is unhurt.

Stands up and fixes the sack on her body.

Straightens her back. Looks,

the bird is gone.

She sends a wary look.

What was the shot?

She worries about her friends

stepping quickly into the barrack,

to arrive inside, to return.

Begin with the woman.

No, begin again with the officer.

His gaze returns to the woman.

She hurries her step,

looking around frightened, anxious,

her pace a near-run.

He still looks at her.

Amazed. Bending down, spellbound,

lifts the bird from the ground.

She’s twitching, her body still warm.

Feels her weight, how tiny she is,

and so pretty,

now he hands the bird to the woman.

Now, please draw the woman.

Hurry, now everything happens quickly,

she takes the bird

as though it was planned,

as though it was obvious,

as though the bird was meant for her,

she takes the bird,

in her hand, without shaking,

she takes the bird

without so much as a look,

she takes the bird,

opens the barrack door,

and enters, now running,

breathless, to her friends,

a little bird in her hand.

The door is now open and she sees

they are not hurt. Now they are all inside.

They worried about her, what was that shot?

Now they are all inside.

And a little bird, dead.

Now they are all inside. And a little bird held in her hand.

Begin with the woman’s friend.

No. Begin with the Blockalteste.

She’s Czech. Religious. Short.

Hides her daughter in a little cabin.

She is good. Begin with the baking oven.

No. Begin with the bird.

Begin, with the pot.

No. Begin with the bird.

Who plucked the feathers out?

Why should the feathers be plucked?

And what does the Blockalteste have to do with the bird?

Begin, from the beginning.

Begin with the bird.

Please draw for me a little bird.

No. Please draw for me a little pot.

No. Please draw for me a little oven.

Look.

Inside the belly of the oven is a pot,

And inside the belly of the pot is a bird.

That you don’t have to draw.

Begin, begin with the woman’s friend.

No, begin with the woman.

The woman is still shocked. The barrack door is closed,

her eyes grow accustomed to the darkness.

She looks at her friends, holds the bird.

No. Begin with the woman’s friend.

she’s older. No, not that old.

She’s still young, just a little more mature.

She takes the bird from the woman’s hands

and walks over to the Blockalteste.

Watch her. How she

grasps the little bird,

elevating it ever so slightly,

and hinting to the little oven.

Gently. And awaits understanding.

Elevates, and hints to the little pot.

She has time.

Elevates, slowly, and hints to the margarine.

Lightly tilts her head to the right.

Elevates, pauses, and hints to the flour.

She has patience. For pepper and for salt.

Look. Now they are huddling in sweet secrecy.

Draw the gaze.

Draw the hunger.

Draw the secret.

Draw the agreement.

Draw the hope. The hunger.

Begin with the hunger.

No. Begin with the bird.

No. Begin with the woman.

With the officer. The gun. With the

with the barrack. The oven. The pot. The bird. With the –

begin already. Come on, begin.

Begin with the memory.

Begin with the, the, with the quiet.

In silence.

Begin with muteness.

Begin with the silence. The silences.

No. Don’t begin.

Just be silent and don’t begin.

And never say a thing.

Don’t write and don’t draw a thing.

Forget all that you’ve said. And be silent.

Erase all that you’ve written. And be silent.

Erase and forget. Forget and erase.

And be silent.

And let go of the barrack. Let go of the officer, let go of the woman.

Let go of the hunger, let go of the gaze, let go of hope.

Leave the silences, leave the voices.

And don’t think oven, or pot.

And don’t touch story, or song.

Expel the bird. God.

Swallow the words.

And be silent.

Forget. Erase. And don’t speak.

And if you must, begin at least with noiseless.

In your head, in a whisper. Whispering.

Begin with the longing. The yearning.

Do you know what bechinalt is? Of course you do.

Begin with the bechinalt.

Draw its aroma rising,

spreading through the house.

Rising from the pot, leaving the kitchen,

crawling to the living room,

reaching all the way to the carpet,

to the radio,

to the search-for-relatives program

making the senses lose their mind.

Begin in the afternoon.

Draw the little apartment in Givatayim.

The sun moves to a diagonal

and a light breeze comes in from the sea.

Begin with mother.

Begin with mother, in the afternoon.

Draw her cooking, a wooden spoon in hand,

explaining to me about flour, and how to make roux.

Begin with mother, afternoon.

Draw her tall, by the stove.

Draw her closely, close.

Draw her touching me.

Begin with me.

Begin with mother, afternoon.

Draw her pretty, on high heels.

It’s the hour of the day when sometimes,

having stopped by the butcher’s and having bought some chicken,

she would cook bechinalt

from a little bird

that she got from an officer

With the taste of much, so much, so very much time.

Translations from the Hebrew

By Elazar Tal Ronen with Lynn Dion

Isis Olivier (https://isisolivier.com), the granddaughter of Sir Laurence Olivier, is a painter of English origin. She lives and works in the Cévennes, a mountain region in southern France. Some of her paintings and prints have been published in France, the UK, and, more recently, the United States and Israel.

Isis Olivier (https://isisolivier.com), the granddaughter of Sir Laurence Olivier, is a painter of English origin. She lives and works in the Cévennes, a mountain region in southern France. Some of her paintings and prints have been published in France, the UK, and, more recently, the United States and Israel.

Editorial note: “littlebird” was first published in 2010 by the Sal Van-Gelder Institute for Holocaust Instruction and Research at Bar Ilan University, Israel, in a Hebrew/English bilingual edition, including an introduction by Hanna Yaoz and an interview with the poet. The booklet was printed in a limited special edition for researchers and students. The poem has been translated into many languages, including Arabic, Hindi, Albanian, French, Polish, Romanian, German, and Swedish.