The Kadesh Peace Treaty and Translating Peace: A Conversation with Anthony Spalinger and Veysel Donbaz

This year marks the centenary of the Paris Peace Conference and the Versailles Peace Treaty signed between the Allied nations and Germany. We do not know if the signatories or architects of the Versailles Peace Treaty knew about the world’s first international peace treaty, the Kadesh Peace Treaty. The Egyptian and Akkadian versions were discovered in the decades before the war, and the full text of the tablets was published after 1912. Today, this three-thousand-year-old treaty can enlighten us about what it means for nations to agree on and craft a language of peace, in this case migrating between Hittite, Akkadian, and Egyptian, to make peace. To get some insight into the world’s first international peace treaty, written in Egyptian and Akkadian, I asked Egyptologist Anthony Spalinger and Assyriologist Veysel Donbaz about Kadesh and the language of peacemaking in the Late Bronze Age.

Iclal Vanwesenbeeck: We call this treaty the Kadesh Peace Treaty today. Did the Hittites or the Egyptians name the treaty?

Veysel Donbaz: The text is named rikilti—“treaty, pact” (between states)—from the Akkadian verb rakāsu—“to bind”—and kešda in Sumerian. The Egyptian copy also attests to it as a treaty.

Anthony Spalinger: There’s no official title, I am afraid, outside of the definition of what the agreement was—namely a “treaty.” But no additional nomenclature was given. But a parity treaty: a treaty between two equal parties. The remaining extant Hittite treaties, despite individual clauses, are all unequal—that is, the Hittite king is superior to the other country/person (land, vassal, etc.).

Vanwesenbeeck: Is this what we’d call today an international peace treaty? I am asking because the Hittites and the Egyptians were the superpowers of the Late Bronze Age, and the Kadesh treaty is, in that regard, a parity treaty between two of the most powerful empires in international politics.

Spalinger: Yes, absolutely. It was a result of the lengthy Egyptian-Hittite conflict that began under Ramesses II’s father, Seti I, and was prolonged for fifteen years or so in the later reign of his son, Ramesses II.

Donbaz: In a sense, yes, because it was prepared exactly like modern treaties giving priority to the country of origin to be mentioned first. This tradition did not start with the Kadesh Treaty; much earlier than this particular era, there were at least fourteen treaties known drawn up beginning with Šuppiluliuma I with the neighboring countries Kizzuwatna, Hayasa, Ugarit, Amurru, Mitanni; with Muršili Ugarit, Hapalla, Kupanta-Kurunta, Manapa-Kurunta; with Muwatalli II, Wiluša, and Aleppo; then comes the treaty between Hattušili III of Hatti and Ramesses II of Egypt.

Vanwesenbeeck: Can we talk about a shared spoken language between the Egyptians and the Hittites that is perhaps analogous to English today? How did they carry out their diplomatic relations, for instance?

The treaty is in the lingua franca of the age—Akkadian—and written on silver (and also on clay tablets—the extant Hittite copies)

Spalinger: Good question. The treaty is in the lingua franca of the age—Akkadian—and written on silver (and also on clay tablets—the extant Hittite copies). In Egypt there were for a long time resident foreigners, scribes we might call them, but better considered to be resident foreigners working in the Egyptian chancellery. At the time of Ramesses II they would be at the Egyptian capital in the north (Avaris = Tell el Dab’a). I suspect that they were partly intermarried with Egyptians, but we have no proof of this. The use of cuneiform for the royal chancellery of Egypt can be confidently dated to the reign of Thutmose III (ca. mid-Dynasty XVIII). And the script (ductus) was not Akkadian. So these residents appear to have come from Asia Minor. I always consider them to be like a “foreign guild” or a “clan of ex-patriots,” permanently living in Egypt at the capital with rather close connections to the royal residence.

Donbaz: The Hittites were in frequent contact with Egypt (for medicine and treatment especially); they had their contact with the help of a foreign language, and it is therefore a well-known fact that they had adopted the Babylonian script in their diplomatic and diverse relations, despite the fact that at that time the Old Assyrian script was very well known and was in usage in Kültepe, Alişar, and Boğazköy.

Vanwesenbeeck: Is there such a genre as peace treaty writing in the ancient Near East? In other words, is the Kadesh treaty, linguistically and structurally speaking, separate from other diplomatic writings?

Spalinger: Yes. It is a parity treaty. Some things are common with other Hittite treaties (fugitives and what to do with them), but the equality makes it unique. And although there are Hittite treaties with Eastern peoples (Syria, for example), writing in Akkadian is typically expected. It is the norm and the lingua franca.

Vanwesenbeeck: The preamble of the Kadesh Peace Treaty mentions the word peace. What do they really mean by peace? And did the treaty bring peace?

Spalinger: It meant the end of any hostility. No cold war as well. Respect of each other’s limits. For eternity (as expected!). It was a very effective peace treaty. We have new correspondence between the Hittite queens and Egyptians in the post-Kadesh period, for instance.

Donbaz: In general, the main aim of making peace with another country lies in the fact that they accept nonaggression, reinforcements, to aid each other when requested, and to recognize the rights of refugees belonging to friendly states (with equal lands). Peacemaking cannot always be in the same tendency and resolution. It depends on the conditions agreed upon and with whom it has been concluded.

Peacemaking cannot always be in the same tendency and resolution. It depends on the conditions agreed upon and with whom it has been concluded.

Vanwesenbeeck: What does it mean for two different peoples with different languages to make peace? Did kings use translators in those times? Did Egyptians and Hittites need translators in negotiating peace?

Donbaz: Certainly, they used translators like today. When we look at the texts we also see a great deal of diplomatic correspondence between the kings as well as queens of the relevant countries, for example letters from Queen Naptera (Nefertari) of Egypt to Queen Puduḫepa of Hatti.

Spalinger: Yes, for sure. But the Egyptian diplomats to the Hittites would have had to have been bilingual in some sense. Actually, I always wonder about the linguistic abilities of the two sides’ representatives! Here, I suspect it meant people, not necessarily “pure Egyptian,” who could deal with Akkadian. I doubt if any person in Egypt understood Hittite, but with international relations—who were the Egyptian representatives at the Hittite capital? In addition, written documents require different linguistic abilities than spoken conversation between two foreigners.

Vanwesenbeeck: Who is the audience for the Kadesh Peace Treaty? Would common people be able to read or understand the texts? I am trying to understand why it might have been translated if not intended for dissemination.

Donbaz: The Hittite nation had a state archive system keeping everything in the palace at the capital. Therefore the audience was the people who were in the service of the government, having been authorized to deal with the documents under the control of the king and his subordinates. I am afraid no one could see them beside the authorized officials. Common people were supposed to be illiterate in this respect, and actually they were. For the very important matters the Hittites used the colossal hieroglyphic inscriptions out in the open air written on the stelae or rocks, for everyone to see. But how they were informed we do not know. But there was a tendency of reading out the treaties now and then in public in the open air in front of the king until he learned the conditions of the treaty. On these occasions the people must have heard of them and also been informed. Although this was mainly applied for the vassals, protectorates, and sons, nevertheless the oral communications must have had an essential role for gaining information.

Spalinger: Ah! You must mean—the present, extant hieroglyphic versions. Not the original at the capital of the Egyptians.

Donbaz: I cannot answer. At Karnak we rely on the accepted scholarly opinion that one was not allowed within all sectors of the Amun temple. But for the more public frontal areas (and no roofs!), high-level persons could go, and probably middle-level ones as well. There are no reliefs—that is, no pictures accompanying the treaty save the standard ones on the top. Yet the space given to it is large indeed. Certainly not “public” in our sense.

Vanwesenbeeck: Would common people be able to read or understand the texts?

Spalinger: Never.

Vanwesenbeeck: For instance, the refugees are a big part of the treaty. Would they have read the text in their respective languages?

Spalinger: No. Actually, how they would be personally affected is a very important question. If belonging to the “state”—that is, as administrators—they might have known about the specific clause stipulations that would affect them, but I suspect not.

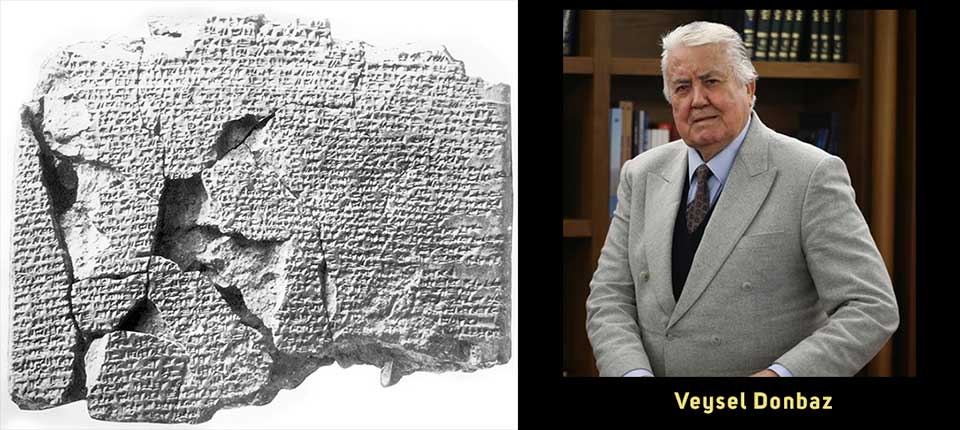

Vanwesenbeeck: The cuneiform tablet in the Istanbul Museum of Archaeology is quite incomplete. How is it with the hieroglyphics? What does it mean for the text to be incomplete in a peace treaty, as you translate it?

Spalinger: The original versions were two (of course), and both in silver. We possess hieroglyphic versions of the treaty as well as cuneiform ones. None of them is an “original.” Indeed, the Egyptian version has a prologue that is not part and parcel of the original item. The Egyptian copies are set within Egyptian temples. And before that prologue the Egyptian version has a date plus the name of Pharaoh Ramesses II. Finally, the Egyptian version at the end refers to the Hittite messenger who came to Egypt with the treaty.

Donbaz: Incomplete means in cuneiform written texts that “it is broken, some parts are missing, broken away on the obverse, reverse, etc.” Sometimes the tablet and the inscription can be complete structurally but the crust could have been badly deteriorated. We can hardly speak about a shared spoken language but a shared written language that was Akkadian-dialect Babylonian. When we look at the Hittite treaties, out of thirty-four of them, nineteen were written in Hittite. Sixteen were written in Akkadian, and nine were written bilingually in the Hittite and Akkadian languages.

Vanwesenbeeck: US Senator Jeanne Shaheen, a Democrat from New Hampshire, recently sponsored the Women, Peace, and Security bill that passed in 2017, and the law now requires that women be included in the peacemaking process. So, I am curious, were any women involved in the making, drafting, and translating, of this treaty, 3,278 years ago?

More than a hundred letters are known to have been exchanged between Queen Puduḫepa and Ḫattušili of Hatti and Ramesses II of Egypt (including their legitimate sons), mostly written in Akkadian.

Donbaz: More than a hundred letters are known to have been exchanged between Queen Puduḫepa and Ḫattušili of Hatti and Ramesses II of Egypt (including their legitimate sons), mostly written in Akkadian. Very few documents have come to light from the Boğazköy archives, which were most likely draft copies written in Hittite. The Hittite queen Puduḫepa is well known to have had direct correspondence with Ramesses II, exchanging letters between them. In a letter from Queen Puduḫepa of Hatti to Ramesses II of Egypt, she calls him her brother, and in one place in her letter (lines 7–16 of reverse) she informs him that “when the messengers traveled to visit the daughter of Babylonia who had been given to Egypt, they were left standing outside Enlil-bēl-nīše, messenger of the King of Babylonia, told [me] this information—should I not have written of it to my brother. . . . Because I already know, I certainly will not do anything displeasing to my brother. Now I know that Egypt and Hatti will become a single country. Even if there is not [now] a treaty with Egypt, the Queen knows thereby how [you] will conclude it out of consideration for my dignity.”[i]

Ramesses II writes her back, saying, “The Sun-god and the Storm-god will give us brotherhood and peace, even in this good relationship in which we find ourselves forever. And our messengers will travel continuously between us forever, fostering brotherhood and peace.”[ii] Line 62 mentions a fact that is mostly gone on the document, mentioning a name of an interpreter: “And [——]-ri, the interpreter, also said the same thing about this situation.” Obviously, it is clear that these letters have been exchanged before the drawing up of the treaty in 1276 BCE. These passages show clearly that there were traveling envoys, messengers, and interpreters between them. One may see the big role of the women in the preparation of the treaty, even if they were not closely involved in the making, drafting, and translating of this treaty, beyond Queen Puduḫepa. She must have had invested a lot of time, effort, and energy in this respect, for she has put her seal on the reverse of the document as the princess of the land of Hatti along with her other epithets.

October 2018 / May 2019

[i] Gary M. Beckman, Hittite Diplomatic Texts, edited by Harry A. Hoffner (Scholars Press, 1996), no. 4.

[ii] Beckman, Hittite Diplomatic Texts, no. 19, lines 26–29.

One of the leading Sumerologists and Assyriologists in Turkey, Veysel Donbaz worked as the head archivist in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum (home of the Kadesh Peace Treaty tablet) from 1968 until his retirement in 2004. He served in programs carried out by the Culture and Tourism Ministry and UNESCO conferences and participated in many international projects, playing a key role in the process of bringing 7,500 Boğazköy tablets to Turkey in 1987. In 2016 he published Bin Kral Bin Anı, Bir Sümeroloğun Anıları (A thousand kings, a thousand memories: memories of a Sumerologist). He is the author or co-author of over seventy articles and other works, primarily on cuneiform tablets.

One of the leading Sumerologists and Assyriologists in Turkey, Veysel Donbaz worked as the head archivist in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum (home of the Kadesh Peace Treaty tablet) from 1968 until his retirement in 2004. He served in programs carried out by the Culture and Tourism Ministry and UNESCO conferences and participated in many international projects, playing a key role in the process of bringing 7,500 Boğazköy tablets to Turkey in 1987. In 2016 he published Bin Kral Bin Anı, Bir Sümeroloğun Anıları (A thousand kings, a thousand memories: memories of a Sumerologist). He is the author or co-author of over seventy articles and other works, primarily on cuneiform tablets.

Anthony Spalinger is a professor of ancient history (Egyptology) at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. He is the author of Time and the Egyptians: Feasts and Fights (2017), War in Ancient Egypt: The New Kingdom (2004), The Transformation of an Ancient Egyptian Narrative: P. Sallier III and the Battle of Kadesh (2002), and Aspects of the Military Documents of the Ancient Egyptians (1982).

Anthony Spalinger is a professor of ancient history (Egyptology) at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. He is the author of Time and the Egyptians: Feasts and Fights (2017), War in Ancient Egypt: The New Kingdom (2004), The Transformation of an Ancient Egyptian Narrative: P. Sallier III and the Battle of Kadesh (2002), and Aspects of the Military Documents of the Ancient Egyptians (1982).