Arabic Literature and Antiquarian Bookshops: A Conversation with Richard van Leeuwen

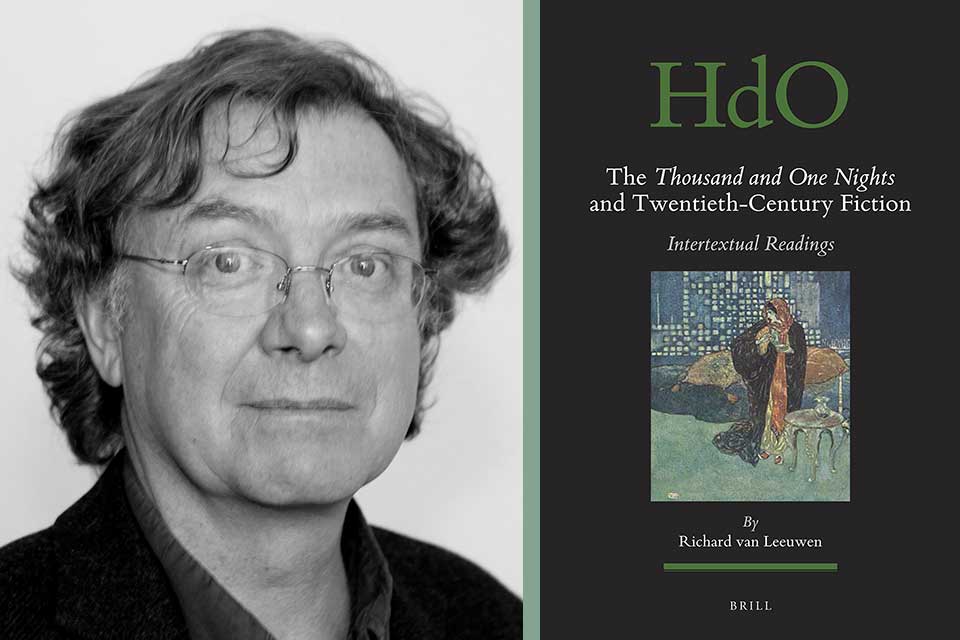

Richard van Leeuwen is a senior lecturer in Islamic studies at the University of Amsterdam. This year, he won the 2020 Sheikh Zayed Book Award in the Arabic Culture in Other Languages category for his book The Thousand and One Nights and Twentieth-Century Fiction: Intertextual Readings, which reveals how the collection of Arab tales supplied an essential source of both inspiration and grounding for many of the writers whose work makes up the twentieth-century literary canon. His book includes analyses of books by both highbrow and popular authors. Additionally, van Leeuwen has published on a variety of other topics, including the history of the Middle East and Arabic literature and Islam. He is also a translator of Arabic literature.

Alex Crayon: You won the 2020 Sheikh Zayed Book Award in the Arabic Culture in Other Languages category for your book The Thousand and One Nights and Twentieth-Century Fiction: Intertextual Readings. What led you to study Arab culture in the first place? What inspired you to investigate the Thousand and One Nights and its connection to the Western literary canon?

Richard van Leeuwen: I started studying Arabic language and culture in 1974, when the Middle East was in the center of attention in the various media, mainly for political and economic reasons. I noticed a general lack of knowledge about Arab history and culture, and I saw a rich field of exploration, both in the domain of history and politics, and in the domain of culture and literature. There was also a touch of romanticism involved, as I started traveling to the Middle East and discovered exciting new parts of the world. I started translating Arabic literature into Dutch during my studies and completed the first Dutch translation of the Thousand and One Nights directly from Arabic in 1999. While working on the translation, I started collecting literary works referring to the Nights as a narrative model.

Crayon: What was the first work that alerted you to the link between the Thousand and One Nights and Western literary tradition? What was it within that work that linked to the stories of Shahrazad and inspired you to write your book?

Van Leeuwen: When I had started working on the translation of the Nights in 1991, I used to pass by an antiquarian bookshop every day on my way home from the university, and one day I noticed a book in the window titled The Last Voyage of Somebody the Sailor, by John Barth. This sparked my interest in the possibility of investigating the traces of Shahrazad’s tales in modern literature. To my surprise, there was hardly any research in this field. I started collecting material, which, over the years, resulted in a huge collection of books. I did not immediately have the idea to compile a book; at first I intended just to examine interesting examples. But the available material became so enormous, and the existing research appeared so inadequate, that I started thinking of a book.

What was especially inspiring was the great variety in the ways the tales were approached by the authors, not merely as a source of exoticism or orientalism, but as part of a complex of literary techniques, narrative strategies, cultural models, and political discourses. I was entering a complete literary universe through the gate of the Thousand and One Nights. Apart from the internet, antiquarian bookshops all over the world have been a vital source of material for my research, so I am very grateful they still exist, not to mention translators, who have made all this material accessible.

Crayon: What was the most fun connection to make and to write about? Did you get to analyze any of your favorite books?

Van Leeuwen: There have been so many interesting discoveries that it is difficult to single out one work or author. I encountered authors of whom I had never heard, such as Gyula Krúdy or Abdelkébir Khatibi, both fascinating figures; I rediscovered Vladimir Nabokov as a literary genius; and enjoyed the narrative complexities of authors such as James Joyce and Italo Calvino. I was especially struck by the use of tropes from the Thousand and One Nights in the interwar period in Germany, by such writers as Ernst Jünger and Rudolf Schlichter, and the references to Aladdin in the Scandinavian tradition, as a personification of the problems of modernity. Who would have thought that the Nights could be pivotal models for writers with such diverse backgrounds and intentions? It was clear that the traces of Shahrazad could be found in the very core of the emerging modernist imagination, not just as a form of exoticism, but to explore essential matters of form and concept. The emergence and nature of literary modernity and postmodernity cannot be explained without referring to the Thousand and One Nights.

The emergence and nature of literary modernity and postmodernity cannot be explained without referring to the Thousand and One Nights.

Crayon: In a webinar interview with The Bookseller, you said that the Thousand and One Nights is the quintessential example of world literature. What does that mean, exactly?

Van Leeuwen: The Thousand and One Nights is a work that explains the essential mechanism of storytelling, and because of this it transcends cultural boundaries. Moreover, as a textual corpus, it is fluid and diverse; it applies the magic that it has “discovered” and reveals in the framing tale: storytelling is required to neutralize traumas, to counter violence, to survive as a human being. From the beginning, it served not only as a quintessential model of storytelling but also as a vehicle for narrative material, which was adapted, transformed, and reshaped to be able to cross all kinds of boundaries and to reinvent itself within new literary and cultural circumstances. It moves between literary fields, it reshapes literary fields, and it is an inexhaustible reservoir of narrative techniques and strategies. It is for this reason that the work has always been used—and is still being used—as a source of inspiration in periods of literary innovation and experiment, for authors all over the world.

Crayon: At one point early in your book, you discuss conflicting views of complete reality within the frame story of the Thousand and One Nights. What role does storytelling have in influencing your reality? What can they do to influence collective reality? Is that the whole point of writing and reading? Or is it simply to shift our personal realities for the moment during which we dive into literature?

In this way authoritarian discourses can be replaced by respect for human values and human diversity.

Van Leeuwen: The basic idea of the Nights is the tension and interaction between diversity and coherence; between differentiation and unity. By telling her tales, Shahrazad breaks up the monolithic worldview of Shahriyar, which is oppressive and violent, and replaces it by a worldview based on variety and imagination. But it does so to disclose the secret of genuine coherence: there is no single reality, there is a reality that is multifarious and can only be contained by the imagination. In this way authoritarian discourses can be replaced by respect for human values and human diversity. So the role of storytelling, of narrative, of the imagination is vital for human survival, not only for Shahrazad, but for society. For me personally, it has been important to discover how many approaches to the basic problem of diversity versus coherence can be imagined: every author has a new and fascinating way of creating his own “battlefield,” hoping to survive in the end. Life itself is a conglomerate of stories that continues until death, which represents the idea of survival.

Crayon: In the Thousand and One Nights, Shahrazad uses a nested form of storytelling to keep Shahriyar entertained each night. What modern parallel to Shahrazad’s storytelling style are you most excited to see develop into a literary style? Are there modern examples?

Van Leeuwen: The device of nested storytelling is one of the crucial “secrets” revealed by Shahrazad as an essential strategy of narration. The form creates diversity within unity and a dialectic between different levels of perception. It juxtaposes fictional and “real” realities in such a way that the reader is drawn into the story, as if their reality is logically the next level of reality implied by the narrative layering. This strategy is exploited in extremis by Georges Perec, in his novel 53 Jours, which contains several interlaced detective stories, suggesting ultimately that the reader is suspected of having murdered Perec.

Crayon: What work of fiction—regardless of storytelling medium—do you think would be a modern equivalent to the Thousand and One Nights in terms of potential influence on the progression of world literary tradition?

Van Leeuwen: The influence of the Thousand and One Nights in literature is still continuing, for instance in the work of the recent Nobel Prize winners Olga Tokarczuk and Peter Handke. But the wheel cannot be invented twice; there will be no second Nights, nor even a work of similar importance. Maybe James Joyce’s Ulysses and Finnegans Wake will in the future be seen as a major watershed, but these works are perhaps too inaccessible for a wide audience. Perhaps the next phase should be sought in the new digital medium: like Shahrazad, who has laid bare the secret of storytelling and the basic mechanism of diversity defying coherence, and subsequently implements her discoveries, whoever succeeds in revealing a similar elementary mechanism related to digital media can have a similar impact on the way narration and imagination are conceived in the future. But perhaps Shahrazad’s narrative magic will just be reinvented and adapted to new forms of communication.

But the wheel cannot be invented twice; there will be no second Nights, nor even a work of similar importance.

Crayon: What’s next for you? What’s your next project?

Van Leeuwen: I am currently working on a large research project about historical accounts of pilgrims to Mecca, a field that has been strangely ignored by scholarship. I study travelogues from early modernity to 1950, not so much as a historical source, but rather as a complex and multiform genre, which reflects processes of historical and cultural change. But I still have an enormous collection of literary works inspired by the Thousand and One Nights, which I would like to discuss in a new book. These are not all famous or important authors, but they do show the deep and structural involvement of Shahrazad in the shaping of world literature from the eighteenth century onward. I hope I will have the time to work on this in the future.

July 2020