“Words Have No Word for Words That Are Not True”

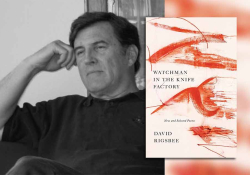

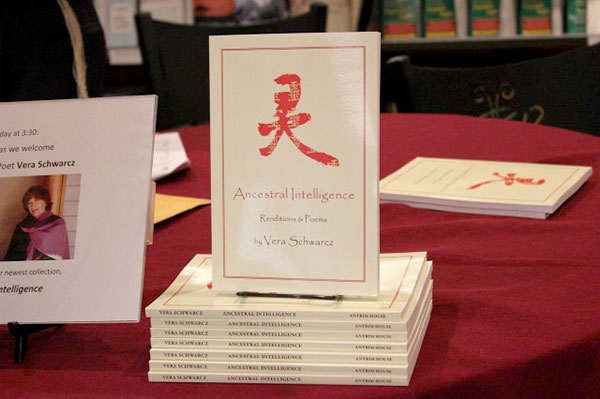

A Review of Ancestral Intelligence, by Vera Schwarcz (Atrium House, 2013)

1

Where thought could not be free,

Death was a more welcome companion.

. . .

Only sages are willing martyrs

For mind’s unfettered reach.

These are lines from Vera Schwarcz’s rendition of a poem by the eminent Chinese scholar-poet Chen Yinke, written in memory of his mentor and friend, the classical scholar-poet Wang Guowei, who committed suicide in 1927 in the face of advancing modernity and the rapid decline of classical culture. In the midst of deep sorrow for his friend’s tragic end and knowing full well Wang’s great scholarly accomplishment in many areas, Chen singled out his friend’s dedication to truth and freedom as his everlasting legacy, as he wrote at the end of Wang’s epitaph: “Independence of spirit and freedom of thought,” as Wang’s life represented, “will last with heaven and earth and shine with the sun, the moon, and the stars.”

This was also the principle that Chen shared with his mentor, and he, in turn, made his own life a testimonial to this principle. Well versed in a dozen languages and generally acknowledged as China’s leading historian of the time, in 1953 Chen received the new communist regime’s invitation to serve as head of the Institute of History in Beijing. Chen’s response was astounding: as a condition of accepting the invitation, he asked that he be excused from all political study and from following the officially endorsed Marxist perspective in historical studies. His demand fell on deaf ears, of course, and he chose virtual exile as a history professor in a university thousands of miles away from Beijing. For the remainder of his life, he dedicated himself to an “unofficial” biographical study of the late Ming Dynasty courtesan Liu Rushi, who killed herself in the wake of the Manchu invasion. Many of his fellow historians were puzzled; they even deplored his effort as a waste of enormous talent. Only in hindsight, years after Chen’s death, did they begin to see the connection between his intensely personal interest in a prostitute of long ago and his deep respect for the great scholar-poet of his generation, Wang Guowei.

Chen decided to live on, a harder choice in the repressive Mao era than Wang’s and Liu’s for final release in the past. As his eyesight gradually failed due to reticular degeneration, his mind’s eye remained open and sharper than ever. He became China’s blind seer or, as Vera Schwarcz calls him, “China’s Tiresias,” foreseeing the increasing ravages of culture and persecutions of innocent people in communist China, including his own tragic end at the brutal hands of Mao’s Red Guards. On the eve of the Cultural Revolution, he wrote a poem that Schwarcz entitles “History’s Rubble”:

This they call

Being human!

Condemned already

a thousand times,

my crime?

I write.

When I can steal an hour

from shouting crowds,

I seek solace in poems

by a courtesan who killed

herself when dynasties

collapsed, when heaven

and earth traded light,

leaving unspeakable darkness.

I’d climb divine heights

to gaze on history’s rubble, find

a sheltering mountain, gentle

leave-taking from worldly cares,

the voice within the silence.

The “voice within the silence” is made of the quiet and stubborn words of The Unofficial Biography of Liu Rushi; it also flows from the sad music of a series of classical style Chinese poems that Schwarcz recreates in English in her book Ancestral Intelligence. These poems, never intended for publication during Chen’s lifetime and now elegantly rendered in another tongue, speak the pains and sufferings, the deeply private thoughts, and ultimately the courage and integrity of a great scholar-poet. They also reveal the truth of history as history is felt and lived by a sensitive human being and speak to readers across linguistic barriers and across “broken time” (a phrase Schwarcz used in her book on Chinese and Jewish cultural memory) about the tragedy of humanity as well as the enduring human spirit during a time of cultural decay and historical darkness.

2

In the beginning was the Word (a rather inadequate English rendition of the Greek logos in Scripture). In the essentially secular Chinese culture, in which agnostic Confucian humanism and transcendent Taoist naturalism complement each other, and in which a written language consisting of logographs has lasted since its invention, the word is intricately combined with history—neither exists without the other. The fabled inventor of logographs, Cang Jie, was the historian for the Yellow Emperor to whom the Chinese trace their ancestry. History for the Chinese is “word made flesh,” at once a story of the past tracing an ancestral line and a revelation of the future like a mirror. The spirit of the word embedded in original Chinese logographs seems to be what Schwarcz means by “ancestral intelligence.”

In early twentieth century, during the New Culture Movement, a radical intellectual trend against traditional culture took root, against classical-style language and the four-thousand-year-old Chinese writing system as well, blaming both the culture and the language for China’s backwardness of the past few hundred years and calling for the elimination of logographs. The surgical procedure on the writing system, however, did not start until the communists took power. With the support of Chairman Mao, the Chinese authorities issued three batches of simplified Chinese characters in the 1950s and 1960s to replace traditional characters as a first step toward completely abandoning logographs and adopting a romanization system. Even though a writing system with simplified characters has become the reality due to the government’s forceful implementation—which distinguished the writing system used in mainland China from the traditional one used in other Chinese-speaking regions like Taiwan and Hong Kong—the project of gradual romanization appears to be a failing, and perhaps already an aborted, program.

What has the simplification of Chinese characters done to China, to the Chinese cultural imagination, and to China’s modernization project? This is the question many intellectuals ask. Schwarcz answers this question with her beautifully imagistic logograph poems in the second section of Ancestral Intelligence. Each poem is a meditation on the contrast between an original logograph (printed in a fluid and elegant classical zhuan style between English lines) and its simplified counterpart (in its dull and rigid block character form as commonly used today). Rather than aiming for etymological accuracy in her reading of the logographs (about which the debates among scholars never end), Schwarcz focuses on the evocative implications and visual beauty that embody the ancestral intelligence and rich cultural imagination in contrast to the impoverishment on all counts in their simplified forms. As a result, each of these poems bears witness in all its concreteness to the desiccation and degradation of culture in Mao’s China that ended with a Cultural Revolution which left behind a vast cultural wasteland. Meanwhile, these poems also pay homage to an ancient language that Ezra Pound once said has to stay poetic.