The Uses—and Uselessness—of Poetry

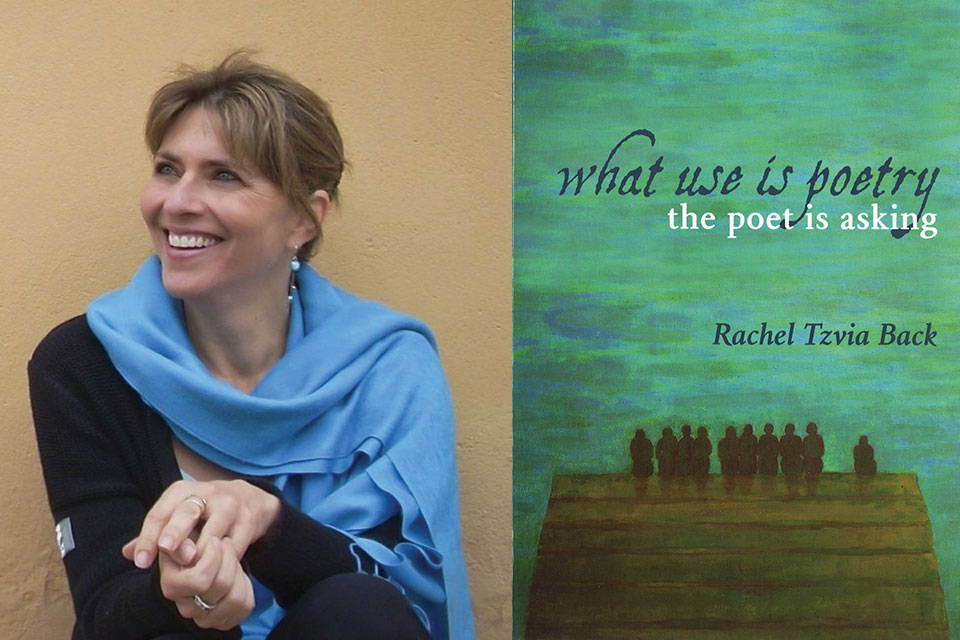

Many poets, writers, and thinkers have dwelled on the meaning of poetry following great tragedy, with Theodor Adorno’s claim that “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric” (“Cultural Criticism and Society”) well known among them. Rachel Tzvia Back’s What Use Is Poetry, The Poet Is Asking (Shearsman Books, 2019) is an invaluable addition to the tradition of such works, in which Back—the English-language Israeli poet, translator, scholar, educator, and activist—grapples with the purpose of poetry in a world of enormous suffering, both for the individual and society at large. The speaker’s mission, as stated in the title, also appears as a refrain in the opening and closing lines of the seven-part eponymous poem: “What use is poetry, the poet is asking / of the evening news [. . .] (9); “what use is poetry, the poet // wants to know” (10); “what use / is poetry, / the poet keeps asking” (18). The reader is not spared from the painful experiences that motivate the speaker to write—war, children perishing senselessly, sons returning wounded from war, and the subsequent grief of mothers, fathers, and sisters. Like Adrienne Rich (likewise a poet, scholar, and activist), who dives down to investigate “the wreck and not the story of the wreck / the thing itself and not the myth,” Back descends into a sea of loss, bringing to bear the tools of language in her possession, to explore whether these tools can matter at all.

Back descends into a sea of loss, bringing to bear the tools of language in her possession, to explore whether these tools can matter at all.

As characteristic of Back’s oeuvre of poetry and translation—including A Messenger Comes (Elegies) (2012), On Ruins & Return: The Buffalo Poems (2007), Azimuth (2001), In the Illuminated Dark: Selected Poems of Tuvia Ruebner (2014), and With an Iron Pen: Twenty Years of Hebrew Protest Poetry (2009)—the personal and political are entangled inextricably in What Use Is Poetry, The Poet Is Asking. The main speaker is a mother whose son “could not avoid going / To war” (12), as he comes of age for mandatory enlistment in the military. The poems are informed by seemingly endless conflicts and tragedies on every side. In the first two poems of the series entitled “Summer Variations,” the only variation is the location where these wars take place. In “Summer (’13),” there is fighting in “the north,” where “they are busy now / slaughtering each other, there’s no time / for flowers” (21). In “Summer (’14),” there is the same fighting, only in “the south” (22).

The juxtapositions of seasons, nature, and death recall images in A Messenger Comes, Back’s previous book, also an exploration of mourning in the context of the speaker losing her father and sister. In “On Edvard Munch’s Melancholy,” for instance, Back writes of “spring and all its lies” (69). In both collections, Back is asking about the “use” of poetry amidst loss. In What Use, the focus is the particular anguish that ensues following “troops moving south,” “boys pulling other boys from the wreckage and flame,” and “whole buildings collapsed from above” (10).

The prolonged effects of war on soldiers and boys, and on the speaker’s son in particular, anchor the volume. It is not only the physical cost of war, but devastation to the spirit and psyche, which resonate throughout the book as a source of Back’s questioning. We encounter the son who “Wept over the dark nightline” (12) and the mother who holds herself responsible for the fact of his being called to war, by virtue of living in the State of Israel. In the third poem of the “What Use” suite, Back writes,

The mother

Who didn’t stop her son

From going

To war –

Was called before the High Court

Of mothers held on full moon nights

At undisclosed Celestial sites, Stars of the Light

Not yet evident on earth the only ones

In attendance.

At the end of this imagined trial, the High Court finds the speaker “lost and forever / Guilty” (12–13). Her son is described as similarly afflicted by guilt in “After the War,” told through the figure of Odysseus, suffering “heartsick” as he tries to return home; the son is “Shell-shocked, he wanders across the seas – / descends // to where his dead reside, together with the self / unforgiven” (87).

It is not only the speaker’s son who suffers devastation but young, innocent children who lose their lives to wars and other forces over which they have no agency. In an exceptionally haunting poem, “Song of the Younger Brother” (for Aylan and Ghalib Kurdi), Back turns her poetic gaze toward two boys who drowned as the family fled persecution in Syria. When reading lines such as “There should be nothing / left in the world / after his little body / on the beach” (38), the reader feels the full weight of sadness and anger over the death of these children. The regular enjambments of the lines punctuate and elevate the pleading of the book. What can possibly be the use for poetry?

The regular enjambments of the lines punctuate and elevate the pleading of the book. What can possibly be the use for poetry?

Moreover, what is the use for poetry in the wake of so much death, which, as Back writes, is permanent and infinite, “because you have died forever” (47)? In the third section of the book, there are poems such as “O” (46), which are to, and about, a lost sister:

O

my very

sister

it is time

is it not

time

you returned

The spacing, fragmentation, and strong enjambments of the lines emphasize the absence of the sister, the yearning for her to “return,” and the implied recognition that she cannot. The poem, as an elegiac address, is an acknowledgment of futility that the speaker can speak (or write) to her sister, but her sister cannot respond. Death itself becomes a space, a void, that cannot be filled.

Back’s speaker does not profess to restore, to perform tikkun, or put things back together; rather, her work suggests that we go forward holding on to what has shattered.

In this void, however, exists a potential answer to Back’s question about the use of poetry in the face of war, death, and illness. If poetry itself can be understood as a site of empathy—and I believe that Back’s collection is such a site—then that is the answer she offers. Back reminds us that a poem cannot restore someone’s life, but it can preserve someone’s memory in perpetuity. Poetry cannot end war, but it can be a means to empathic expression. Back’s speaker does not profess to restore, to perform tikkun, or put things back together; rather, her work suggests that we go forward holding on to what has shattered.

In the final poem of the collection, Back ascends from the depths, returning to the initial impetus of the book, with a tentative revisiting of poetry, “Like the believer who wakes into faithlessness.” Acknowledging her loss of faith in poetry—described as akin to a religious person losing faith in god—the speaker “puts one more poem / on the page” (93–94). Turning toward these tragedies, honoring the memory of those who have been harmed or have perished, and teaching us how to live amidst this grief are but some of the “uses” of poetry in What Use Is Poetry, The Poet Is Asking—its gifts.

Tel Aviv

Editorial note: Back’s poem “After the War” first appeared in the March 2017 issue of WLT. Her essay “‘A Species of Magic: The Role of Poetry in Protest and Truth-telling (An Israeli Poet’s Perspective)” was published in May 2014.