Transcendence and Exhortation in the Haitian Poetry of Jean Métellus

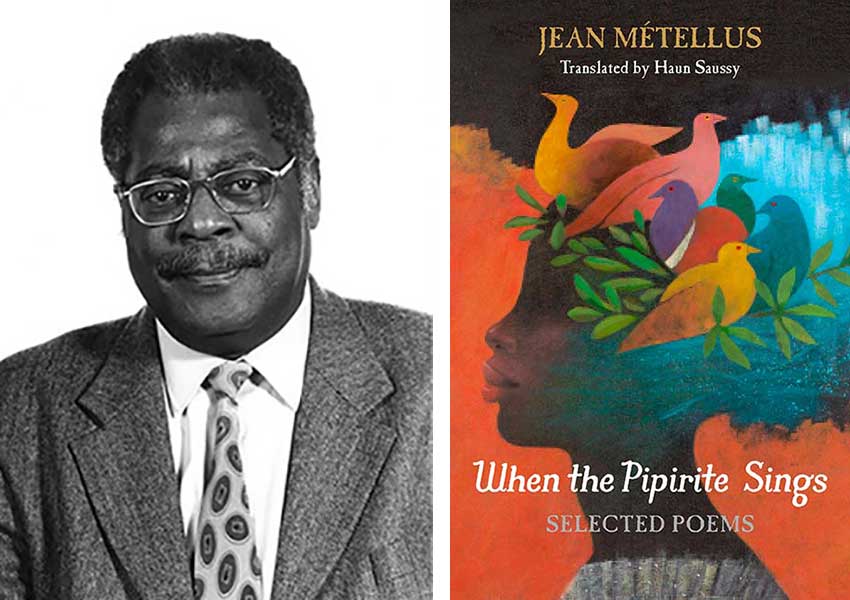

Dany Laferrière was elected to the French Academy in 2013. Edwidge Danticat won the prestigious Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 2018 and is the recipient of a MacArthur “Genius” Grant. Jean Métellus’s 1978 Au pipirite chantant was translated into English for the first time in 2019: When the Pipirite Sings: Selected Poems, translated by Haun Saussy (Northwestern University Press). Hopefully these events signal a growing interest in Haitian writers in the English-speaking world.

Métellus (1937–2014) had lived in France for nineteen years when he published his first poetic volume, Au pipirite chantant, which owes its title to Métellus’s signature poem. Unlike Césaire and Laferrière, Métellus’s poetry is void of raw hurt and militant anger. Like Danticat, Métellus affirms that words transcend geography and time and spur the hunger to write everything. It is thanks to the lifelong dedication of Métellus’s wife, Anne-Marie, and to years of labor by Haun Saussy (see WLT, July 2009, 38–39), that we can grasp today the full significance and terrible beauty of a land scarred by slavery and poverty, a land so deeply attached to its French cultural heritage that not even seventeen years of American military occupation have left a visible trace in its literature. And we can see that there is much more to the work of Haitian writers than folklore.

We can grasp today the full significance and terrible beauty of a land scarred by slavery and poverty, a land so deeply attached to its French cultural heritage that not even seventeen years of American military occupation have left a visible trace in its literature.

The poems of When the Pipirite Sings are admirably translated with attention to the poet’s changing “voices”; the Kreyol words are explained at the bottom of the page. The selection of poems revolves around the titular poem’s focus, which Saussy augmented with thematically similar yet shorter poems, some of which come from different poetic volumes. This liberty to let the poetic corpus reinvent itself was already present in the French publications. Au pipirite chantant was republished in 1995 with a new selection by Claude Mouchard; later, several of its poems were eventually incorporated in other volumes. Likewise, Saussy’s inspiration for this volume is palimpsestic. His foreword is a revised version of an earlier published essay, and his translations were made over a decade, here for a class, there for a journal, and even for a dance recital, in the case of “Ogoun.”

A sixty-page paean to his native land, “When the Pipirite Sings” is a drama in three parts; first, a thirteen-page prologue setting Haiti as the scene of a cosmic struggle between good and evil; then a seven-page “Prayer to the Sun” for the violence to stop; and finally a forty-page section, “The Sun’s Reply.” The song of the pipirite, the first bird to sing in the morning, returns the imagination to the land and the time to the beginning of a new day, like an incantation. The poem catalogs every event, leader, feeling, or thing known, experienced, felt, and remembered by the land of Haiti and its people. In this kind of encyclopedic mono/dialogue, the poet “talks” the people and the land, becoming their voice, alternating Vodou, folklore, evocations of the beauties of nature, and the people’s travails. The narrative “I” occurs infrequently, as if the poet and the sun were interchanging voices. Throughout this geste of the land—part nostalgia, part sacred inspiration, part quasi-surrealistic chaos of remembrance and feelings—Métellus captures the soul of Haiti in a sweeping, breathtaking diorama of images and colors, smells and words that help him into a new understanding, in much the same way by which the biblical character of Job sees his faith change to an open and vibrant one.

Métellus tells about Haiti’s brokenness, but, more importantly, he paints its soul with transcendence and acceptance, confession and a quiet exhortation.

Métellus tells about Haiti’s brokenness, but, more importantly, he paints its soul with transcendence and acceptance, confession and a quiet exhortation. A survivor of the Papa Doc dictatorship, Métellus refused to be amputated from the sacred breath of inspiration, something he expressed in a “coda” poem of the 1978 edition. When time stops at dawn and the poet takes the measure of his life, he gains the perspective of wisdom. The following translation is mine.

Circonvenir l’aurore

Et repasser le temps

Presser les heures choyées par la brise du bonheur

Comme le fleuve nourrit ses poissons

Et la forêt ses futaies

Le temps de dire le jour

Ce qu’on découd la nuit

Le temps de coudre la nuit

Ce qu’on délie le jour

Le temps de contempler

Les rides sereines de la foi

Les orgues sacrées de la loi

Le temps d’écouter dans cette pâle insomnie

La voix étouffée de la vie

Circumvent dawn

And relive time

Seize the hours blessed by a gleeful breeze

Like the river feeding its fish

And the forest its tall trees

The time to tell by day

What we unstitch by night

The time to sew by night

What we untie by day

The time to contemplate

The serene wrinkles of faith

The sacred music of the law

The time to listen in this pallid insomnia

To the hushed voice of life

University of Tennessee at Martin