Sylvia Plath’s Fertile and Flowering World

As a girl in high school during the early aughts—in that new and suckling millennium so naïvely sure of itself—this is what I knew of Sylvia Plath: that if I read her work I would bind to it, immediately be embarrassed for being such a cliché and equally terrified of my own suicidal possibilities. I had already fallen heavily into Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, which allowed me the disorienting thrill of empathizing with a literary suicide without having to contend with an actual one. What I sensed then, but wouldn’t put into words until many years later, was that Edna Pontellier’s fatal swim into the ocean was only compelling to me because of what it represented: a woman’s radical refusal of expectations. When I finally turned to Plath’s writing over a dozen years later, I found that same urge toward self-determination, this time fearless and in language that rapidly lit its way through my body. Her work has been integral to my sensibilities as a woman, as a poet, and as a mother ever since.

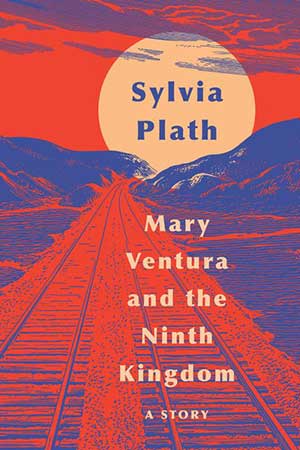

I wonder now how much sooner I might have allowed myself to move beyond our societal reduction of Plath’s writing if her recently released short story, Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom (Harper Perennial, 2019), had also been required reading in high school. A fairy tale both sinister and emboldened, it begins with a young woman’s entry into adulthood and ends nowhere near where it was so perilously heading. Each page reveals just enough information to entice and confuse. Newsboys cry out headlines, “Extra … ten thousand people sentenced … ten thousand more people …” while Mary’s parents carry out a suspiciously ordinary emptying of their nest. The woman knitting a green dress next to Mary on the train informs her that the smoke tinting the sun a strange and unfamiliar shade of orange is from fires in the north—the direction in which Mary is headed. We never learn exactly which parts are meant to be pure allegory, which more concretely harkening to the dark and sinister history of the decade before it was written in 1952, but there is one ringing clarity. In Mary’s world, as well as ours, the dire necessity of female agency is always up against its own constant, preened, and fully normalized defeat.

I wonder now how much sooner I might have allowed myself to move beyond our societal reduction of Plath’s writing if her recently released short story, Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom (Harper Perennial, 2019), had also been required reading in high school. A fairy tale both sinister and emboldened, it begins with a young woman’s entry into adulthood and ends nowhere near where it was so perilously heading. Each page reveals just enough information to entice and confuse. Newsboys cry out headlines, “Extra … ten thousand people sentenced … ten thousand more people …” while Mary’s parents carry out a suspiciously ordinary emptying of their nest. The woman knitting a green dress next to Mary on the train informs her that the smoke tinting the sun a strange and unfamiliar shade of orange is from fires in the north—the direction in which Mary is headed. We never learn exactly which parts are meant to be pure allegory, which more concretely harkening to the dark and sinister history of the decade before it was written in 1952, but there is one ringing clarity. In Mary’s world, as well as ours, the dire necessity of female agency is always up against its own constant, preened, and fully normalized defeat.

Mentioning or alluding to red over twenty-five times in forty pages, Plath manages not to overwhelm but to build her use of color meticulously along with the reader’s sense of disorientation. The effect is electrifying, the insinuation of violence always hovering just below the surface of the page. I can’t help but see “the woman in the ambulance / whose red heart blooms through her coat so astoundingly” when, ten years later, that same violence would rise in her work alongside the startling arrival of “Poppies in October” (Ariel).

There are a number of moments in the story that are difficult to see apart from the aura of their author, making them all the more difficult to judge on their literary merits alone. As during the rise of narrative arc, when the woman in brown abruptly reveals the ninth kingdom to be “the kingdom of negation. Of the frozen will.” Or later when she admonishes Mary, saying, “You let them put you on the train, didn’t you? You accepted and did not rebel.” The rest of this allegorical story is so adept at continually revealing just enough that I’m inclined to believe I would have been less forgiving of these recklessly obvious moments if they’d been written by anyone else. It’s equally difficult to decide if I love her jarring use of words like “incognito” and “hieroglyphics” amidst so many one- and two-syllable words, or if I only love imagining them in her voice. Each time I linger over this indecision, I think back to the very first line of the story, “Red neon lights blinked automatically,” and I’m stunned all over again. That last word feels so audacious! After five spaced and breathless syllables, she ticks off five more in just one word, carrying with it equal parts banality and menace. So much of the story’s deeper meaning is at once hidden and captured within that first line.

What this story, and so much of Plath’s work, has to offer is what we are still in desperate need of: an example of a woman utterly empowered by her ability to choose. The ability to choose more than what women were, and are, made to know from birth as the only viable life: to marry, to have children, to be suppliant, and wholly dependent. Mary chooses otherwise and in doing so arrives, not at her death, but at a fertile and flowering world that has been waiting for her.

University of Oklahoma

Editorial note: To learn more about Plath’s high school friend named Mary Ventura, whom Plath in her journal described as “something vital, an artist’s model, life,” see Peter K. Steinberg, “Sylvia Plath’s Mary Ventura.”