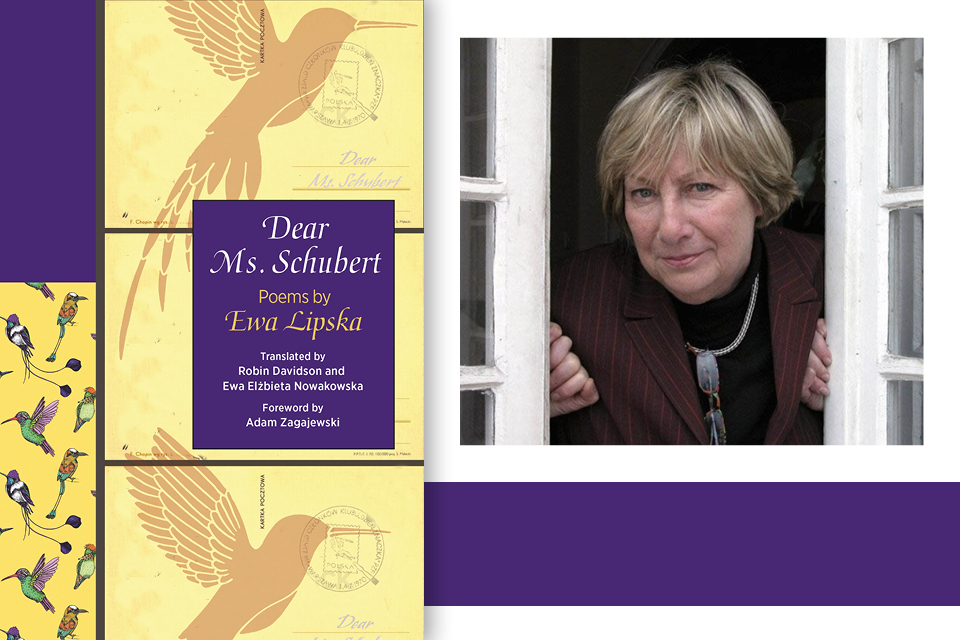

Poetry as Sounding Board: Ewa Lipska’s Dear Ms. Schubert

Released shortly before the death of Adam Zagajewski, Ewa Lipska’s Dear Ms. Schubert (Princeton University Press, 2021) benefits from a foreword in which he praises its author as a solitary writer who, like her friend Wisława Szymborska, revolted against the conventions of “women’s” poetry. Along with Anna Świrszczyńska and Julia Hartwig, Lipska (b. 1945) is credited with transforming the nature of the feminine lyric since 1945. Adding to their ranks are her two translators, Robin Davidson, a translator, academic, 2015–2017 poet laureate for the city of Houston, and finalist for Texas State Poet Laureate in 2017 and 2019, and Ewa Elżbieta Nowakowska, a prized and published translator and poet selected by Zagajewski as one of Kraków’s emerging younger poets. Finally, at the heart of Dear Ms. Schubert is yet another woman, the mysterious and elusive Ms. Schubert, to whom the volume is dedicated. Davidson and Nowakowska have included all of her appearances in Lipska’s work, starting with three poems from Ludzie dla podzątkujących (People for beginners), one poem from 1999, and three poems from Pogłos (Echoes). The main part of their volume is comprised of Droga pani Schubert (Dear Ms. Schubert) and Miłość, droga pani Schubert (Love, dear Ms. Schubert), which were published in quick succession in 2012 and 2013, and comprise twenty-six and twenty-eight poems, respectively. Dear Ms. Schubert evolved from the translators’ fascination with this evocative character that endured in Lipska’s work for sixteen years.

Who is this Ms. Schubert who serves as the depository of her lover’s musings, becoming a reverberated sounding board?

Ms. Schubert, the recipient of postcard prose poems, seems to have crept into Lipska’s life as discretely as her epistolary admirer, Mr. Schmetterling (Butterfly), who evokes their nostalgic past steeped in Viennese cafés, secret lovers’ codes, Ferris wheels, promenades on riverbanks, erudite readings, hand-sewn coats, and tender meetings in hotel rooms. Such continuity in a poetic opus characterized by constant renewal tells of a broader endeavor behind the personal story of two elusive people. Larger themes emerge for the reader who cares to gather clues, namely a chronotopic panorama of German-speaking culture, and of the multilingual and multiethnic ties of central Europeans to the German world. The panorama stretches over two centuries, examining culture from leisurely nineteenth-century philosophical pursuits to brutal twentieth-century mass murder and totalitarianism. Who is this Ms. Schubert who serves as the depository of her lover’s musings, becoming a reverberated sounding board? She is the mirror of the fragmentary remembrances of a man who seems to never age. What if, like Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, the ageless Ms. Schubert traversed the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, an archetypal female east-central European figure whose personality and world can be reconstructed through fragments of memories of her own actions, sayings, or indications of her social habit and historical context? Could this be an intimation of Lipska’s feminism? Or might she be this woman who states, “I am a date; in me there is no place or time” (127)?

This is a revolutionary act, a democratization that anchors Lipska’s poetry in spoken and written nonliterary texts and gives it the rhythm of breathing.

The fascinating puzzle Lipska has put in front of us continues with the blurring of the boundary between prose and poetry. According to Lipska herself, the poems were written as prose postcards, and indeed only the poems of Dear Ms. Schubert are set as free verse poems. This is a revolutionary act, a democratization that anchors poetry in spoken and written nonliterary texts and gives it the rhythm of breathing; its speaker/writer perceives the world in a particular, poetic rhythm. Thus hemmed in by this mode, Lipska’s images take acrobatic, surrealistic liberties: the solo singer flips the switch in his throat; music spreads its incurable diseases in the form of concerti, nocturnes, and serenades; photographs must be turned upside down to understand ancestry; rain washes words from lips; love explodes in a book; and rumors abound about stories that never took place. The world’s engine is taken apart and reconstructed haphazardly from memories that are fragments in a game of distorting mirrors in which memory fades slowly, despite the poet’s admonition to take a diet supplement of memories three times a day (65).

Ewa Lipska debuted in 1967 and has authored more than twenty volumes of poetry, six volumes of collected poems, and three volumes of prose. She has been translated into twenty languages; ten volumes have appeared in Serbian since 1998; nine volumes in French since 1996, thanks to the indefatigable work of Isabelle Macor; and eight volumes in English since 1981, Canada being the first Western country to publish her, eight years after she won the Kościelski Prize, and before she won several more prestigious prizes.

University of Tennessee at Martin