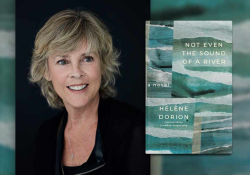

Poetic Transcendence: Exploring Kiriti Sengupta

“A thing of beauty is a joy forever,” and our aim is to reach the unattainable, the unknown through the “viewless wings of Poesy.” “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” thinks the Romantic poet, Shelley, and Kiriti Sengupta has created his own world by the subtle strokes of his brush; it is an endeavor to achieve the unobtainable, in the garb of familiar, commonplace words.

“And come I may, but go I must, and if men ask you why, / You may put the blame on the stars and the sun and the white road and the sky”—this fervent appeal as expressed in “Wander-Thirst” is replete with a profound philosophical analysis of life as an unending voyage. Poetry too is a journey from transience to permanence, from mundane to the spiritual, and from carnal to metaphysical. Sengupta has set out pm this journey with an overview of the world around him and in his poetic trilogy, Dreams of the Sacred and Ephemeral (Hawakal, 2017), he blends the “sacred” and “ephemeral” to make a complete whole.

At times, readers feel the presence of an omniscient narrator telling the story while interrupting and addressing them. My Glass of Wine, The Reverse Tree, and Healing Waters Floating Lamps (the three constituent books of Sengupta’s unique trilogy) are woven meticulously, keeping in view a sense of unity. The style also is fine-tuned with the themes, making the poetic trilogy a mirror of the society.

At times, readers feel the presence of an omniscient narrator telling the story while interrupting and addressing them. My Glass of Wine, The Reverse Tree, and Healing Waters Floating Lamps (the three constituent books of Sengupta’s unique trilogy) are woven meticulously, keeping in view a sense of unity. The style also is fine-tuned with the themes, making the poetic trilogy a mirror of the society.

Poetry as a reflection of contemporary society aims to explore new arenas of life. “A musician must make music, an artist must paint, a poet must write, if he is to be ultimately at peace with himself,” said Abraham Maslow, and Sengupta undoubtedly adheres to the notion, considering poetry his existence. His poetic journey bears the fruits of his extensive reading and thorough knowledge of ancient scriptures, the Vedas, and the Bible, among other religious texts.

The Earthen Flute (Hawakal, 2016) sets the tune of religiosity in a different perspective and tries to analyze the strange connection between religion and humanity through poetic imagery. “Among those three eyes of Durga / The third one has been the same / over the ages / It has been kept open / Full or half.” This apparent simplicity behaves like a “deceiving elf,” as we read between the lines we feel the presence of a “third eye” governing the entire cosmos. The implicit mockery in the concluding lines, “They have been experimental / Only on her earthly eyes,” reveals the alarming ambivalence between the “earthly” and the “spiritual.”

Sengupta’s poems occasionally dwell on the seamy side of our existence and thus impel readers to identify the agony hidden under the veiled rapture of human life. “Moon—The Other Side” is a case in point where the poet deliberately deals with the poverty-stricken faces living under the spell of moon-washed night: “Do you remember the bread / Sukanta left behind? / It was baked in / The blaze of a full moon night.” We are to live in a society where “even the moon has its share of crevices / with restricted entry of light . . .” Sengupta alludes to Sukanta Bhattacharya, noted Bengali poet, to reinstate the image of full moon as bread made by the blow of destitution.

Sengupta’s poems occasionally dwell on the seamy side of our existence and thus impel readers to identify the agony hidden under the veiled rapture of human life. “Moon—The Other Side” is a case in point where the poet deliberately deals with the poverty-stricken faces living under the spell of moon-washed night: “Do you remember the bread / Sukanta left behind? / It was baked in / The blaze of a full moon night.” We are to live in a society where “even the moon has its share of crevices / with restricted entry of light . . .” Sengupta alludes to Sukanta Bhattacharya, noted Bengali poet, to reinstate the image of full moon as bread made by the blow of destitution.

In The Earthen Flute, Sengupta brings out the essential paradox of religion, which urges us to remain “sacred.” At the same time he says that religion is also a gateway to our unfulfilled desires: “Prayers carry lives within / They are expressions / Our desires take refuge in.” We tend to reach the zenith, and the unbridgeable gap between dream and reality makes human life an expression of an eternal quest: “Wishes are chanted with closed eyes / And we continue to live being frightened.” Our bizarre eyes always look for miraculous escape from the mundane and the profane, and the more we move away from God, the more we enter a self-centered, claustrophobic universe.

Poetry is an expression of life in its myriad forms, and The Earthen Flute takes good care of them. Sengupta’s pen touches upon the untold stories of religion and humanity, and he thinks of the misery of mother earth when she was invaded by the British. History comes out as a living entity in some of Sengupta’s poems; he envisions India as a country bearing the pain of the Partition, blood oozing out of its soul: “Elderly Mujibar has no money; he owns a hovel and a large pond. Mujibar eats rice and boiled Shapla as he returns from work. He grows Shapla in the pond that also has Lotus in it.” The traditional Shapla (water lily) of Bangladesh and lotus, the national flower of India, are intertwined in the poetic frame, and Sengupta gives us a verbatim record of Mujibar’s lifestyle, Mujibar being a representative of penury-stricken Bangladesh. The apparent simplicity of this prose poem takes us back to history and tries to blend the real and make-believe in the strong undercurrent of passion.

“Physiologists say the womb can withstand / Much stress and strain,” writes Sengupta in “Mother Water” (The Earthen Flute), a tribute to the holy Ganges encompassing the journey from womb to pyre. He has portrayed Ganga as an incarnation of suffering, and this poem offers a silent prayer to our holy mother.

Sengupta’s poems occasionally dwell on the seamy side of our existence and thus impel readers to identify the agony hidden under the veiled rapture of human life.

Is poetry a mirror of life reflecting pleasure and pain or a hymn of suffering humanity? Do we really want to get rid of the pain inflicted upon us due to the presence of the Shara-Ripu (six enemies)? Or do we need to get rid of suffering, as Buddha envisaged Nirvana (liberation)? Sengupta has raised pertinent questions with reference to scriptures, especially the Gita, and Reflections on Salvation (Transcendent Zero Press, 2016) is, beyond doubt, a journey within. The eighteen brief chapters “stir the age-old notion about sacrifice, renunciation and salvation,” says Sengupta.

“With saffron comes sannyas or renunciation, and with renunciation arrives attachment. Attachment with the world, attachment with domesticity, or maybe the gods.” Sengupta pours out his notion about renunciation, categorically demolishing the much-hyped concept of tyaga (sacrifice) as associated with saffron. The color symbolism is brilliantly interwoven with the underlying theme of this prose poem.

“With saffron comes sannyas or renunciation, and with renunciation arrives attachment. Attachment with the world, attachment with domesticity, or maybe the gods.” Sengupta pours out his notion about renunciation, categorically demolishing the much-hyped concept of tyaga (sacrifice) as associated with saffron. The color symbolism is brilliantly interwoven with the underlying theme of this prose poem.

“We do not need magic to change the world, we carry all the power we need inside ourselves already,” said J. K. Rowling, noting the shift from the theocentric to the anthropocentric world starting from the Renaissance. Then why do we perform yajna as a tool of liberation, or a magic-kit to bring happiness to our lives? This rhetorical question haunts Sengupta as he thinks of the “amount of ghee” burned in the sacrificial fire.

Sengupta’s inquisitive eyes search for facts and figures, and his poetry is an embellishment of truth with a stylistic presentation. He finds out subtle nuances even from known facts. “No matter if you sacrifice your sweat and blood, or feel exhausted, you are to consider yourself duty-bound. . . . Bhabapagla, the great philosopher, might have connected beauty to duty, but did he count on our appearance?” The realization embedded in these lines shows the gateway to “paradise” through our work.

“Bairagya sadhane mukti se amaar noy / Asankhya bandhan-majhe mahanandomoy / Labhibo muktir swad” (I don’t seek salvation in renunciation / In the ecstasy of innumerable bonding / I’ll savor the joy of emancipation). The profound philosophy expounded by Tagore takes us to the esoteric world where peace lies in harmony and liberation in bonding. “We live as long as we breathe; and it is but the breathing which occurs on its own will. No gods, but the breath that builds a home for our life and death”—the penultimate lines of Reflections on Salvation come out as a gush of wind guiding us to come to terms with the real world, shaking off all our dreams of salvation.

The journey from “salvation” to “stillness” with an “earthen flute” setting the tune of this poetic venture bears semblance to a real-life adventure, which makes readers travel in the realm of poetry. Kiriti Sengupta, sometimes, serves as the travel guide. His mighty pen has scribbled verses “with restraint,” and his reading of Indian mythology, history, and religion is reflected in his work. Sengupta’s short yet highly suggestive poems lead readers in a certain direction, and he makes use of a proverb that takes us back to the ages of Kalketu and Phullara: “Phullara says: ‘The ants grow wings to fetch death.’”

Creation is undoubtedly a product of loneliness and turmoil, and Solitary Stillness (Hawakal, 2017) establishes that dictum in no uncertain terms: “And then you can see the resurrected spirit / approaching your stillness / and challenging the world / to leave you alone.”

Creation is undoubtedly a product of loneliness and turmoil, and Solitary Stillness (Hawakal, 2017) establishes that dictum in no uncertain terms: “And then you can see the resurrected spirit / approaching your stillness / and challenging the world / to leave you alone.”

Poetry, as a medium of protest, has stood the test of time, and in Solitary Stillness, Sengupta too has raised a few relevant questions challenging the age-old conventions: “Did Jesus keep silent / when they nailed him to the cross?” Life never remains stagnant; it flows and collects whatever comes on the way. Poets too keep an eye on the world around them and weave the pearls to make a necklace. Sengupta as a voyager has traveled through the inroads of poetry, and his realizations come out in terms of poetic metaphors. At times he warns of annihilation that may destroy the birds: “I’m not aware where the birds hide / when they are unwell, but / I can say, birds heal themselves, / and die solitary / amidst the quiet flora—unnoticed!”

Obliteration or annihilation is not the final note. Sengupta has touched upon the diverse aspects of human life like an observer and jotted down his feelings and experiences like self-revelation. The deliberate use of enjambment tends to draw a line of demarcation between the real and the unreal, the prosaic and the poetic. “They emerged from their mortal frames / thinner / but didn’t hesitate to grow longer / and even surpassed / as we went ahead / Our shadows cherished / every bit of the lightlessness // until a sudden gush of glow bathed us” (“Illumination”). We too are bathed in the glory of light in the luminous words of poetry. The prose poem “Poetry, Cricket and Two Neighborhood Countries” uniquely combines poetry with the agony of the Partition, and this poem serves as a memoir to enkindle our passion for an undivided India. “Last week India fought against Bangladesh, it was an international cricket tournament. They were defeated . . . oh hell! We bad-mouthed . . . they were hell bent and spoke highly about their sportsman spirit” (Solitary Stillness). The willful spaces in some lines suggest a deep-rooted animosity between the two countries. Poetry as a philosophical pursuit lays stress on the temporal world as transient and ever-changing.

History comes out as a living entity in some of Sengupta’s poems; he envisions India as a country bearing the pain of the Partition, blood oozing out of its soul.

Sengupta also brings philosophy in his poetry, making us aware of the evanescent glory of existence. “And, the sky won’t allow the clouds / for long. They will rather find / another summer / to captivate and tantalize” (“Rolling Stone,” Solitary Stillness). A critic’s eye penetrates the world of poetry, its stylistic features and embellishments. The focus of the present essay is slightly different as it aims to find out the soul of the poet and his deep insight into the vibrant life. The road from The Earthen Flute to Solitary Stillness has been traveled with an intuitive spirit to explore, to come across frontiers of human experience. The words are skillfully coined, and the poet tends to avoid ornamental structures to make his poems a replica of real life. His words float spontaneously like water lilies, and we, the readers, get drenched in verses. It’s an expedition through the labyrinth of solitude, thereby making us aware of the paradigm of loneliness. “I no longer seek company. To my utter bewilderment if the ghost succeeds to appear, I’ve decided to offer it a chair first, and then I’ll plead, ‘Take a seat and relax. Let us share our stories . . .’” (“In Conversation with . . .”).

It’s a realization that it is much better to live in solitude instead of being confined in a golden cage. These words are echoed in the unforgettable lines of Virginia Woolf in The Waves: “How much better is silence; the coffee cup, the table. How much better to sit by myself like the solitary sea-bird that opens its wings on the stake. Let me sit here forever with bare things, this coffee cup, this knife, this fork, things in themselves, myself being myself.” The journey must go on; the poet must delve into the “heart of darkness” to liberate words in the “clear light of day.”

Sengupta’s poetic images will certainly enrich readers to strive to explore the hidden layers. At times the sugar-coated pill appears to be heavy to digest, as in his self-opinionated remarks about saffron, meditation, sacrificial beasts, and salvation. Well, truth is always bitter, be it in poetry or real life; in spite of the warning against speaking bitter truth, “satyam bruyat priyam bruyat na bruyat satyam apriyam” (speak the truth—speak coated truth—don’t speak bitter truth), literature opens up a mirror to bring out the pulp from the kernel.

Sengupta’s poems too can be looked upon as a quest for truth, at times replete with irony and sarcasm. He has done justice to his poetic expedition, and it’s an untiring effort to find the nectar with the extended hands of his poetic Muse.