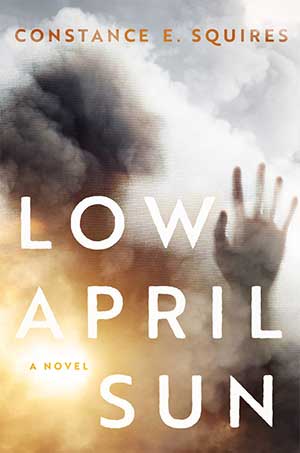

Nobody’s Innocent, or Everybody Is: Constance E. Squires’s Low April Sun

Those who have not suffered trauma directly tend to think of it as an event. It is not. Trauma is an atmosphere; trauma terraforms, creates a new world in which one must relearn how to function, how to proceed, and, ultimately, how to grasp the quality of healing this new world offers. This truth applies no matter if the trauma is individual or collective. Such is the content and focus of Constance Squire’s new novel, Low April Sun (University of Oklahoma Press, 2025).

The 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City is the novel’s inciting incident. As the narrative unfolds, the impact of this tragic event on four characters is explored: Edie, a recovering alcoholic; Keith, her husband, a gambling addict yet to hit rock bottom but seemingly hellbent on getting there; Delaney, Edie’s half-sister and Keith’s then-girlfriend, missing since the bombing, presumed dead but not officially listed as such since no remains were ever recovered; and August, a self-harm addict, caught in an amber of his own ritualized penitence, convinced a single different decision might have altered events on that terrible April day in 1995.

The 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City is the novel’s inciting incident. As the narrative unfolds, the impact of this tragic event on four characters is explored: Edie, a recovering alcoholic; Keith, her husband, a gambling addict yet to hit rock bottom but seemingly hellbent on getting there; Delaney, Edie’s half-sister and Keith’s then-girlfriend, missing since the bombing, presumed dead but not officially listed as such since no remains were ever recovered; and August, a self-harm addict, caught in an amber of his own ritualized penitence, convinced a single different decision might have altered events on that terrible April day in 1995.

The various coping mechanisms of Edie, Keith, and August offer an exploration of the self-reflexive role of guilt and punishment. Their choices are flawed, misguided, sometimes dangerously dysfunctional, but Squires treats those choices, and the characters making them, with the light, understanding touch of grace. Yes, our efforts to heal often tangle us up in snares of our own making. But we have to do something. Low April Sun acknowledges and honors this compulsion with an unflinching, steady gaze.

Squires treats those choices, and the characters making them, with the light, understanding touch of grace.

While Squires adopts the Murrah bombing as a jumping-off point, as context for her characters’ growth, the novel is not interested primarily in exploring the question: “How can such horrific events happen?” (although some exploration, given that same context, is unavoidable), tackling instead the much more important question (since such horrific events inevitably and invariably do happen, again and again): “What do we do now?” Squires’s deft handling of dual timelines—1995 and 2015—allow us to see how Edie, Keith, and August address that question, until a Facebook friend request from someone who may or may not be Delany appears. Scabs are pulled off, all-new questions must be asked, and the shape and form of healing must reimagine itself.

Because Squires understands the complexities of her subject matter, she steers clear of answers. The central question of “what do we do now?” is never tidied up; she avoids hollow platitudes and neat, trite, and ultimately unuseful aphorism. The closest we come to a definite statement on that central question comes in a midnovel conversation between Edie and August:

She pointed at a spot behind me. “We found the SUV she [Delany] drove over there. And her jacket,” she pointed to the middle of the memorial, “was recovered over there. I always knew she died here. Knew it. But now? I don’t know. Maybe those people who told us they couldn’t count her among the dead were right not to. Maybe she’s not a victim.”

“But you are.”

“What?”

“You are.”

She looked confused. “I never thought of it that way.”

From a craft perspective, the writing in Low April Sun is masterful. Perfectly paced character development. Dual timelines distinctly separate but seamlessly blended. The string of plot connections ideally placed—including a brilliantly positioned Delaney chapter that whets the reader’s appetite for answers and accelerates the narrative pace—to create an unfolding suspense that never feels constrained or tainted with a Dickensian arbitrary convenience. Squires treats her characters with a grace we all want to be ours. Yes, her characters are flawed, but they are also us. We recognize ourselves, our limitations, our foibles, our demand for impossible answers, our pain and suffering in them, and because we do—and because the narrative in Squires’s hands demands we do—we blend with them, point our gaze where theirs is, see what they see, hope what they hope, despair when that shared vision becomes all too recognizably opaque.

Squires’s characters are flawed, but they are also us.

But the novel suggests that opacity comes from asking the wrong question. The title of the novel refers to the setting of a moment of clarity for Edie, when the question of “why” morphs into the relevance of “who,” along with all the obligations and responsibilities that come with that word. It is no longer a question of the tragedy or the trauma, but of how we define ourselves in relation to tragedy or trauma. Low April Sun is, beyond all else, an important book because it reaffirms the importance of “who,” the essential signification of the word. For you. For me. For everyone. For somewhere in that word lies truth. And in that truth lies, in turn, the healing we seek.

Oklahoma City