On the Brink of Silence

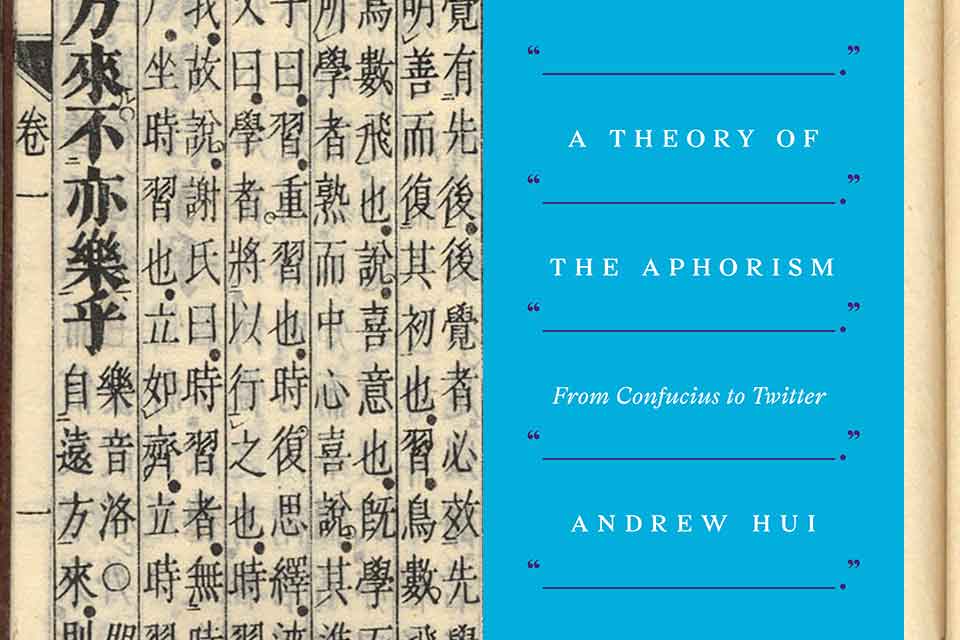

In A Theory of the Aphorism: From Confucius to Twitter (Princeton University Press, 2019), Andrew Hui makes a lot out of a little. In this short book he is “interested in aphorisms as philosophical fragments and systems, and their hermeneutic inexhaustibility” (213). He honors aphorisms that evoke “the ever iterative process of infinite becoming” (20). Aphorism epicures will find aphorisms about aphorisms, like Nietzsche’s “The aphorism, the apothegm . . . the forms of eternity” (154). If you have a hankering for infinity, eternity, or inexhaustibility, this is a book for you. Read it if you can.

But first, a few caveats. Hui presumes that interruption, digression, and repetition are “the rhetorical modes that best represent the human condition” (132), and so he interrupts, digresses, and repeats. And repeats. And repeats. Readers prone to nosebleeds should beware his hyperboles.

From the start Hui announces that his theory does not apply to all, or even most, aphorisms but rather to aphorisms that take a stab at philosophy. “The theory that this book advances is that aphorisms are before, against, and after philosophy” (2), which should account for all time zones. The standard band of theorists—Benjamin, Blanchot, Deleuze, Derrida, Foucault—make cameo appearances. Hui’s theory is, he says, “a” theory, not “the” theory; others are possible. How does his hold up?

Hui chose seven aphorists to make his case: Confucius, Heraclitus, the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas, Erasmus, Bacon, Pascal, and Nietzsche. No lightweights in this ring. Each of the seven aphorists represents a distinct era; the eldest have distinct traditions. To compare these seven, Hui read Chinese, Greek, Latin, English, French, and German, maybe Coptic, too. His epilogue sums up with Sanskrit and Pali; at the end as the beginning, Chinese.

Hui cites the best editions. For Confucius and Jesus, who wrote nothing, he cites their best secretaries. Each of his seven is male, but Hui also praises Simone Weil’s “luminous, aphoristic Gravity and Grace” (144) and reminds readers that the Marquise de Rambouillet, Marquise de Sablière, and Marquise de Sablé wrote aphorisms alongside La Rochefoucauld (128). Brilliant though they are, the aphorists of Paris and Versailles sparkle outside Hui’s theory.

Readers might miss celebrated aphorists. Solomon, Cato, Gracián, Goethe, Emerson, Wilde, et alia, get barely a nod or nothing at all. Other aphorists and collections of aphorisms are tucked in a concluding bibliographic essay. Hui doesn’t need them; his philosophic selection restricts him very little. Philosophers have long been productive of aphorisms, or suspicious of them, building up quite a corpus, pro, con, and exemplary. Hui’s seven gave him a base large enough to get him wherever he wanted to go. Why Confucius? He gave Hui more aphorisms than Lao Tze and less trouble than the Buddha would. With his pick of the pre-Socratics, he seems to follow Democritus (he pursues “atomized” literature [18]) but chose Heraclitus, sage of “dark sayings.” Jesus and Pascal speak for Christianity, Nietzsche for eternity. There is one conspicuous absence: Kierkegaard, whose Philosophical Fragments, Diary, and Either/Or would fill another chapter.

For Hui, philosophy knows no limits. His definition of aphorism—“a short saying that requires interpretation” (5)—has few qualifiers, thus more freedom. The crux of the definition is “short,” of course; we’ve known since we were sophomores that every text requires interpretation. Aphorisms require more interpretation than most: Hui believes some have “infinite horizons and inexhaustible depths” (21). He cites a few, short as a single word (see below).

Hui expands his range another way: he diverts to first and second cousins of aphorisms: maxims, adages, dicta, proverbs, epigrams, gnomes, sententiae, parables, pensées, anecdotes, apothegms, precepts, quotations, fragments, and metaphors. His epilogue echoes Twitter’s tweets.

Hui’s choice of seven has a surprising chapter: he chose the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas to speak for Jesus. That Gospel interests historians of religion because it barely survives; a single damaged copy was found in the Nag Hammadi desert in 1945. Long forgotten, it is almost new. Perhaps its time has come. The Gospel appeals to learned Christians because it expands the Christian world. It appeals to Hui because it conveniently collects 114 of Jesus’s aphorisms, or (to be skeptical) 114 aphorisms attributed to Jesus, one after the other. Who would not want to know them? What do they teach? Why suppress aphorisms?

Aphoristic scripture tempts Hui into theology. A few chapters later comes aphoristic science, and with it another large expansion.

Anything called an aphorism is good enough for Hui. Francis Bacon, one of England’s greatest aphorists, stuffed his Essays with them. Surprisingly, perhaps to tack to philosophy, Hui studies the “aphorisms” of Bacon’s Novum organum rather than those of the Essays. The definition of “aphorism” thereby enlarges enormously because, “In general, Bacon makes no distinction between aphorisms and axioms” (204n39). Neither does Hui, conceding that aphorisms of the Novum organum are not short, nor are they “aphorisms in the conventional sense” (111; see also 10). When Bacon refers to “aphorisms” as the “pyth and heart of Sciences,” he means axioms, as Marlowe did in his Faustus and Coleridge did in Aids to Reflection, not wit, spiritual guidance, or winged words, nothing but plain truth. Hui makes do.

With lightning speed, Hui moves between aphorisms and fragments. For Hui, “fragment” bundles three different things: lost works, unfinished ones, and excerpts; a fragment can be a sentence, a paragraph, or a tall pile of Nachlass.

“It is crucial,” Hui writes, “to draw a tight nexus between aphorisms, fragments, and classical scholarship” (13). Why?

In eternal recurrence, Hui’s book will peak with Nietzsche, Hui’s nexus incarnate.

Because aphorisms, fragments, and classical scholarship are spacious, in fact “infinite.” Hui will not be bound, not by a theory or a definition, even his own. With his choice of seven aphorists, Hui guaranteed his book did not need to confirm a theory. All it had to do was put this group together and let them mix.

Hui is scrupulous citing sources. He introduces each aphorist favorably. Confucius, the eldest, comes first; the rest follow chronologically. Regardless of their eras, they lead Hui to the same point: “there are infinite ways of reading a finite saying” (41). Erasmus added erudition. Pascal added anxiety.

In eternal recurrence, Hui’s book will peak with Nietzsche, Hui’s nexus incarnate: a polyglot philosopher, philologist, and aphorist. Like Nietzsche, Hui admires aphorisms that withstand the abuses of history. “Philosophies come and go, theologies rise and fall, but the aphorism abides” (82). Hui’s favorite aphorism is from Nietzsche: “What good is a book that does not even carry us beyond all books?” (176, quoting Gay Science, §248). Possible answer: good enough if it leads to better books.

It is not every day that you read a scholar able to connect Chinese to Greek classics, who cites Renaissance and Wilhelmine philology, and who disdains sniping and sneering. Fans of dense brevity will appreciate that A Theory of the Aphorism is packed tight as a walnut. It quotes Callimachus, “Big book, big evil” (102). It is replete with small things. A scholar of microforms, Hui compacts the aphorism into something even smaller, a metaphor: a seed (92–96).

It is not every day that you read a scholar able to connect Chinese to Greek classics, who cites Renaissance and Wilhelmine philology, and who disdains sniping and sneering.

The book ends with a Zen word: “zengo, a verse into a word. One word contains within it an infinitude of meaning. Finite aphorism, infinite signification” (187). Hui’s final words are four examples: Stillness, Silence, Emptiness, and Circle (188).

Hui’s book is fare for all aphoristic appetites. Insatiable readers will recognize Hui as one of their own.

Champaign, Illinois