In Between Coming and Leaving: Kiriti Sengupta’s Water Has Many Colors

Do you get jabbed by a question that seemingly appears ceaseless? Bob Dylan’s song “Watching the River Flow” hints at a matter bound to raise a query. The point is: where does the river flow to? Is it headed somewhere? Do we spare a minute or two from our busy schedules and ponder on such matters? Because all we can possibly aim for in our life unfurls as the antithesis to revering the moments we live for. But the problem remains the same, as one is not interested in borrowing T. S. Eliot’s words: “disturb the universe.” Otherwise, the riptide of a weary life is bound to throw one into the sea of troubles. Why troubles? Because humans feel that their lives are composed of them. More than what the crisis offers, some people simulate it more and more to convince themselves a further crisis awaits. Life’s howling edict impels one to “run” instead of “just live, only for a moment.” It is important to choose the alternative sometimes; at least that won’t do any harm. Kiriti Sengupta’s newest collection, Water Has Many Colors (Hawakal, 2022), is no rarity in such a context.

Feed the earth water

Feed the earth water

she flows in abundance.

Allow the planet to breathe:

the air is her consort.

Free her from plastics—

they choke progress.

She endures the mess

her wards make. (“Hibiscus”)

The above lines wake us to the ignorance the world has evoked and embraced. Sengupta asks one to be sensible toward Mother Earth since it allows us “to breathe.” Her lap serves as succor anent silence amid worldly barbarity. This assistance is due to the feminine and motherly warmth akin to that of a mother. Sengupta evinces androgyny—the trait embedded intrinsically in his verse to personify the compassion of Mother Earth. Deliberately choking the progress, as he says in the above lines, is direly menacing. It is an appeal to stand up against the looming peril and do the needful. This harm to ecology is akin to what Anton Chekhov reported in his play Uncle Vanya, where the character Dr. Astrov says: “The forests are disappearing, the rivers are running dry, the game is exterminated, the climate is spoiled, and the earth becomes poorer and uglier every day.”

Chekhov wrote this play more than a century ago. He had foreseen the impending doom much ahead of his age. And to live in that knowledge and ignore relentlessly is nothing short of recklessness to which the world writ large is exposed. Sengupta’s inherent trait in Water Has Many Colors remains overtly visible; his use of explicit images isn’t a cul-de-sac. Instead, the simplistic textures of his narrative get fused with the free-flowing environs.

Sengupta’s keen eye for simple images reveals a malaise with the world, which can gnaw at the unwary reader without prior notice.

Sengupta’s keen eye for simple images reveals a malaise with the world, which can gnaw at the unwary reader without prior notice. Arguably, many of these poems also carry a fin de siècle reflection of vocabulary and its ally in identity. In “Vernacular,” he offers:

Snivels are his lingo of wabbit.

Berceuses fail to dull him.

Pats on his posterior

offer no repose.

Here, Sengupta’s sense of conflict serves as a standard guide: not only through the outcomes of tension, both natural and unnatural, but also through an awareness of the identity that builds and retains us. Language is the basis of our edifice, the crux of our existence, and the fundament of our decisions. Identity is one of the most sacred things that go hand in hand with the language with which we are born or the one that grows on us like another being. Slumber is no more a necessity but a duty that berefts us of the option of “repose.” It is so because “Berceuses fail to dull,” therefore, the tranquil moment gets robbed by squandering our thought process. Language defines our choices and, in turn, our thoughts. We tend to ornate it to exhibit the luxury of thinking and our choices. But language is nothing but a vessel that is meant to choose sides. “We can’t find the source”—perhaps we don’t intend to. However, it is the source of our roots that define us. Sengupta wedges a notion familiar in Satyajit Ray’s Agantuk through the choices that we think we make rationally: “Nobody forgets their mother tongue if they don’t want to, and those who do, forget it within three months.”

Thoughts result in scribbling into empty spaces, whereas one’s vernacular imparts life into it. What essential components make up a choice, and how does language reconcile the energy gathered in the space throbbing before and after us? This is not a mystery but a conscious choice to forget, “which parents wish to recall.” By parents, perhaps Sengupta hints at every individual to whom their thoughts are child, and they should not suffer before it’s late by recalling what they had lost.

Travelers gather around the Baul.

What does he chant?

Melody unfurls . . .

Govinda manifests across

the bank of Ajay. (“Bucolic Bengal V”)

According to the Bauls, their objective is to achieve the Finite–Infinite–Elusive in the human body. Their aspiration is to be freed from the awareness of light and darkness, infinity, and life and death and to feel an unending sense of immortality above all. The chant can range from Visibilia ex invisibilibus (the Visible is born from the Invisible) to Om Vajrapani Hum (one can learn to access Vajrapani’s boundless and fiery energy). In both cases, “Melody unfurls” speaks of the realm that has not been plowed, reminding us of the neighbor we do not see or choose not to—

Near my home there is a mirror-city,

and my Neighbor dwells in it.

All around the village is fathomless water.

The water is boundless,

and there is no boat to take me across.

I yearn to see Him,

(but) how shall I get to that hamlet? (“Lalon Fakir”)

Lalon refers to the neighbor that resides within us in the above lyrics. Even though we live close by, we can’t see him. Yet, through the mirror, one can procure cognizance into one’s being. The quietude of everyday pastoral life, combined with the optimistic components of humanity, result in the poems of the “Bucolic Bengal” series, meant to be read slowly, and ambulated lightly beside.

Poetry doesn’t only function to emulate the cadence of some intellectual theorists or great artists, but images from everyday life can also form the crux of a poem.

Poetry doesn’t only function to emulate the cadence of some intellectual theorists or great artists, but images from everyday life can also form the crux of a poem. As Sengupta does in the prose poem “Intrinsic,” where film stars are questioned about their “first break,” nobody asks a lawyer, a doctor, an engineer, or a researcher the same. Also, “Multiplex,” a three-line poem, talks about the void resulting from the dissipation of single-screen theaters—

Bedbugs bite no more.

Popcorn and beverages

offer frequent intervals.

The friendly banter, the apprehensive kissing, lovebirds holding hands in trepidation, the jubilant cheers and disturbing whispers, murmurs, and their apparent intrusion—Uff! Hush! Either let us watch the film or leave—have ceased to exist. Now only “Popcorn and beverage” strive as the focal point, whereas the film is secondary and rarely paid attention to.

In “Nostalgia,” Sengupta talks about the first meeting he had with a professor named Samantak Das, who died by suicide a few months ago.

I met him once in Santiniketan.

Exchange of courtesies

beyond a hearty bonjour—

he waned through the misty lane

for his routine walk.

Social media deploys memories as “Newsfeed pours in recollections.” Remembering the “Exchange of courtesies” happened once, although readers might wonder whether it was a memorable meeting or just a fleeting moment. However, the prancing statement in “Nostalgia” ascertains Sengupta’s class as a poet: “Impromptu earns recalling / when consumption lingers.”

Memories are stored in boxes, and when recalled, even a fleeting moment can heave a weariness that can’t be rid of as the weighty one takes a toll in a manner “when consumption lingers.” By memory, I think about another poem in the book. Sengupta elicits how decadence, which is detrimental if not acknowledged, is a holistic memory in the garb of exhibitionism:

Aesthetes preach Tagore.

Officials display replica of

the Nobel Prize. (“Santiniketan”)

The above lines clearly show how authorities indifferently flaunt the replica and uphold the glory of a culture. The void remains not because the Nobel Prize got stolen but because of the “display” of the replica. Memory concerning a certain glory got replaced by dictums delivered by “aesthetes” over the years.

Water Has Many Colors comprises monostichs that are incredibly heavy with their profundity.

What if I am mute or loud? (“Prayer”)

Does prayer really work? Or are we afraid? Why do we pray in silence? Doesn’t rage have a part to play in worship? All these questions summate when one reads the line, and every time the interpretation changes. This is political in every single way. Our interpretations result from our choices while expounding the above line.

Breathing banks on black market. (“Covid-19”)

Our essential breathing was challenged by the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. People in power turned this fragile situation into an opportunity that rolled in their favor, thereby inducing a “black market.” This delirious situation was also discernible in Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, which he wrote at a time when humanity was ravaged by a plague. Strangely, there was a lockdown, and the year was 1607. The play tells the story of a crisis created by an unbridled fascist force. When the people fumed with anger, Coriolanus was banished from the crowd. Sicinius reminds the nobles of an essential truth that they seem to have forgotten: “What is the city but the people?” (Coriolanus, III.i).

Water Has Many Colors is delicately crafted and exquisite, both still and eddy from start to finish. Sengupta has not deliberately experimented with the form for exhibitionism, but the honest attempts are perceptible. After reading the collection of poems, one can hear the colors and see the sounds of a flowing river. Ranging from prose poems to monostich, Sengupta evokes the path he has treaded throughout his life. Life’s offerings galore are just uniquely different, as he puts forth:

Water has many colors,

smudging pebbles

along its path. (“Spectrum”)

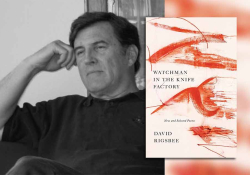

The illustrations by Rochisnu Sanyal complement the poems and do not flaunt any skill. Limiting oneself and satisfying the purpose accordingly is a challenging task. Mr. Sanyal does it brilliantly, keeping a signature of his own.