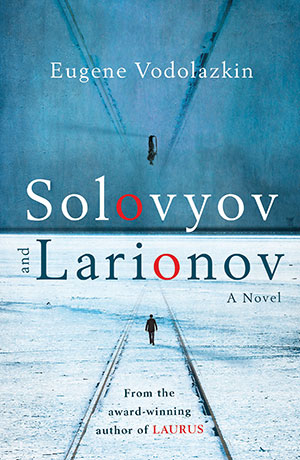

Solovyov and Larionov by Eugene Vodolazkin

London. Oneworld. 2018. 404 pages.

London. Oneworld. 2018. 404 pages.

Russian novels have a common reputation for being hefty books, but despite the page count and the sweeping subjects that justify the size of hefty masterpieces like War and Peace, Crime and Punishment, Doctor Zhivago, or The Gulag Archipelago, these books are surprisingly intimate in exploring the main characters, with authors scrutinizing the details of their souls and feelings, like quantum physicists seeking to find the truth of the entire universe in its tiniest particles.

In Eugene Vodolazkin’s Solovyov and Larionov, Solovyov is the subject under minute examination. A young historian at the beginning of his career, he finds his subject in General Larionov, who led White Russian troops against the Bolshevik revolutionary army, but who, after his defeat in the Crimea, evacuated what men he had left, put the rest in disguises, and waited to meet his enemies in his own uniform. Larionov was one of the most effective generals of the White Army, a legend on the battlefield, and the Reds were never known for their forgiving nature.

What happened after that is unknown, except that the general not only survived the years of Lenin and Stalin and died in 1976 unmolested by the Soviet government, he even retired in his upper-class family’s home, though compelled by the local council to share it with various other comrades—some of whom were executed for political reasons. Did he make some kind of deal that has been lost in the state records? Did he betray his men and their cause? Was he a deep agent working on behalf of the Bolsheviks? This mystery of why Larionov was allowed to go on living obsesses Solovyov, at the very least as a means to establishing a scholarly reputation, and sets him on a search for the unpublished memoirs of the general.

Summarizing the plot like this makes the quest for the truth of Larionov seem like the driving force of the book, but instead it is more of a clothesline along which the events of Solovyov’s life are displayed. Born by a remote railroad stop of six buildings grandly named “Kilometer 715,” Solovyov knows few people growing up, and the train infrequently stops there. He walks a long way to school and salves his loneliness with books in the regional library. He even develops a crush on the librarian, who is very much not the kind of woman who collects crushes, from schoolboys or anyone else, but the drabness of Solovyov’s existence is brightened by the magic in the books. Later, he awkwardly discovers sex with a local girl who, some years later, becomes the object of another search, and then, when he goes off to university in 1991, has a relationship with a fellow student in the city, who helps him recover some of the missing parts of Larionov’s manuscript.

The novel is more than a beautifully written coming-of-age story. The story of Solovyov’s growth is interspersed with his research into Larionov’s life, and the variations in the written history demonstrate the elusiveness of historical biography. Detailed lists of the numbers of weapons like sabers and cannons lend a feeling of exactitude to some of Solovyov’s research, but then he discovers that stories attributed to an otherwise reliable source may actually have originated from a different general, somehow becoming folklore. The historical record becomes as fluid as any other life story passed on by word of mouth. That certain things happened can sometimes be verified. Others can only be verified by the fact that they have been repeated endlessly in multiple sources. The motivations behind various actions, however, may be shaded in each retelling, until ultimately these rememberings become whatever the interpreter wishes them to become. Larionov is a legend, but what is legendary is not confined to history. Each of us works hard, even if unintentionally, to make a legend of our own lives.

All this sounds very serious—and it is—but Solovyov and Larionov often has a comic tone that keeps it from being just a philosophical bildungsroman. The depiction of the academic world in which Solovyov finds himself will be familiar to anyone who has ridden the scholarly merry-go-round. The oddball professors roam the university halls, mutter their implausible interpretations of the historical record, and bitterly condemn other colleagues’ work. The feuds, as the old joke goes, are so bitter because there is nothing significant at risk. Solovyov’s mentor offers advice on academic gamesmanship. A panel session drones on with self-important pronouncements, long after it should close, with the audience impatiently longing for drinks and dinner. The landscape of academia is somewhat routine in its absurdity, and oh so easy to satirize, but Vodolazkin manages to convey the comedy of academia without turning satire into slapstick. The seeming silliness of scholarly pursuits is counterpointed with the serious intent of Solovyov’s research and with the emotional and intellectual satisfactions of discovery and insight that all genuine scholars feed upon. Vodolazkin himself is an expert on Old Russian literature and knows this landscape well but, even more to his credit, portrays the thinking processes that go into historical study brilliantly.

There is, in many translated books, the scent, if not outright stench, of translation—crude attempts to approximate in one language the culture and thought processes of the other. It is therefore particularly delightful to read a novel that does not remind you on each page to make allowances for slightly awkward wording and quaint phrasing. Vodolazkin is particularly lucky. There is no need to make any allowances. Lisa C. Hayden’s translation is all but invisible. The writing comes across as extremely adept yet relaxed. Often, it can only be described as beautiful. It allows the reader to stay in the story, in the characters’ heads, and in the flow of ideas without the nagging distractions of strained equivalencies. From the first page, I knew this was going to be a very well-written book, and then, because it did not seem translated, had to remind myself that indeed it was. I cannot read Russian and have no idea if the original manuscript is as well written as the translation, but Solovyov and Larionov as I read it is one of the finest novels I have read in years.

J. Madison Davis is the author of eight mystery novels, including The Murder of Frau Schütz, an Edgar nominee, and Law and Order: Dead Line. He has also published seven nonfiction books and dozens of short stories and articles, including his crime and mystery column in WLT since 2004.

J. Madison Davis is the author of eight mystery novels, including The Murder of Frau Schütz, an Edgar nominee, and Law and Order: Dead Line. He has also published seven nonfiction books and dozens of short stories and articles, including his crime and mystery column in WLT since 2004.