Love and Sexuality in the Fallen World of Ma Jian

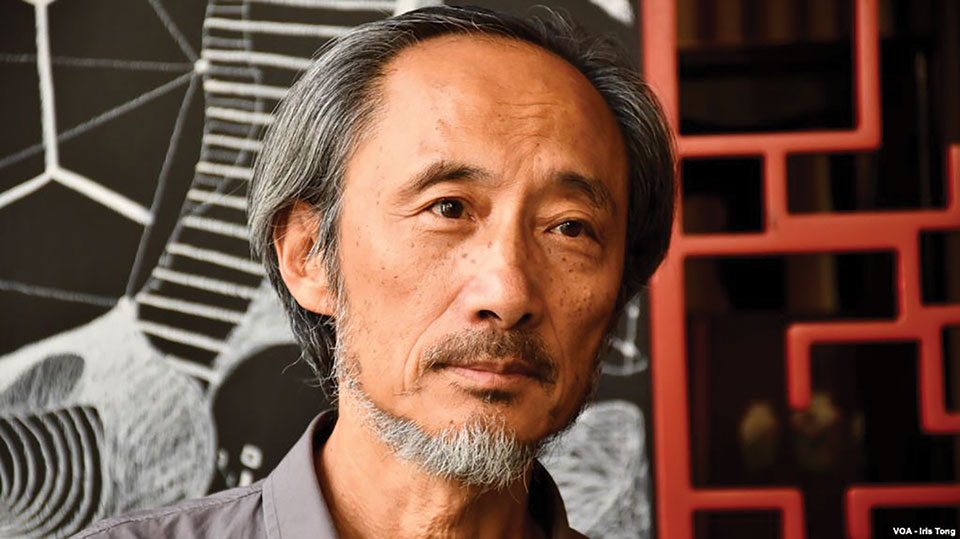

Reviewing Ma Jian’s three-decades-long career, Elizabeth Fifer traces the banned and exiled Chinese writer’s deepening critique.

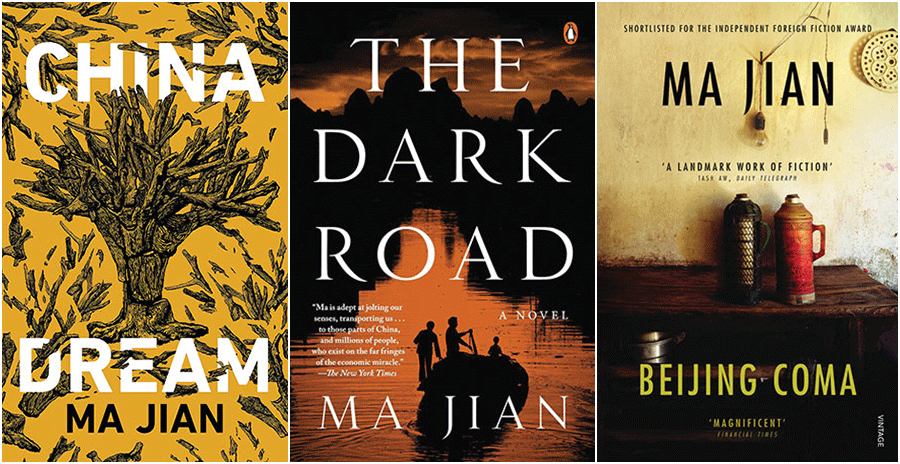

A newly translated work of fiction by Ma Jian, China Dream (2018), provides an opportunity for celebration and a reconsideration of his distinguished career. He is one of the most respected and discussed of all contemporary Chinese authors. His work is known worldwide, except in China. His devastating wit and experimental style are used to deconstruct both the history and the political reality of everyday life in China. Now living in exile, he has written fiction on subjects as diverse as Tibetan culture (Stick Out Your Tongue, Eng. 1987), urban life (The Noodle Maker, Eng. 2004), the repercussions of the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 (Beijing Coma, Eng. 2008), and China’s one-child policy (The Dark Road, Eng. 2013). Red Dust (Eng. 2001), about his three-year trek across China, gives readers a sharp and thoughtful memoir of rural life. His gifted translator is Flora Drew.

After Stick Out Your Tongue, his collection of brilliant and unflinching short stories, appeared, all of Ma’s work was banned from future publication in China and all copies of the book confiscated. One newscast called it “vulgar and obscene”; it was accused of defaming the Tibetan people. The government labeled Ma a “pornographer.” Black-market copies circulated, and the book was widely read.

The exaggerated charge of pornography arises from the centrality of love and sexuality in Ma’s work. He arrived in Tibet a recently divorced man who had lost custody of his daughter. The anger and loneliness in the stories spring from a sense of personal loss and political injustice. The characters Miyama in “The Woman and the Blue Sky” and Sangsang Tashi in “The Final Initiation” vividly illustrate Ma working at the intersection of love and sexual violence.

Both stories concern the abuse of innocent women, forbidden love, and rape. The structures of tradition and religion fail. Sangsang Tashi falls in love with a fellow monk. Forced to marry two brothers, Miyama dies in childbirth. Before Sangsang Tashi can enter her final illumination, the head lama rapes her and she dies in an icy river.

The naked bodies of the two abused women, one dismembered to feed the vultures in a sky burial, the other food for fish, are eloquent. The brothers scatter Miyama’s flesh dispassionately. The lamas will verify even a corpse as the manifestation of the Living Buddha.

After the feverish nightmare of the Tibetan stories, Ma uses his black humor and critical eye to dissect contemporary Chinese life in The Noodle Maker. It is framed as a discussion over dinner between two old friends, a professional writer and a professional blood donor. One uses his imagination to survive; the other sells his blood. One lives for ideals, the other for profit. The blood donor brings the dinner. Stories follow like strands of noodles fashioned from the dough of the professional writer’s brain. As Mao instructed, the writer goes down among the masses for his subject. The blood donor interrogates each character, such as the lovesick, suicidal actress, the street writer who pens letters of protest and longing, the talking dog who describes how his kind would run the world.

Committees can debate reforms, but when a streetlight goes out, a woman is sure to be raped.

The waves of change transform China, forcing people into “reeducation,” self-criticism, and spying. Successive campaigns and party memoranda create a shifting political landscape. In an unsettled atmosphere of suspicion and fear, people struggle to keep up with current trends. Committees can debate reforms, but when a streetlight goes out, a woman is sure to be raped. A picture on a soap wrapper of a blonde woman in a swimsuit teeters between the pornographic and the healthy until Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door Policy approves it.

The professional writer calls his “the wasted generation,” left in a spiritual vacuum, without the means to understand foreign culture or appreciate its worth. He asks, “How can a society numbed by dictatorship find its way in the modern world?” The blood donor says people have become indifferent to the suffering of others, that they lack pity, compassion, or respect. The dog explains, “Everything is decided by your superiors—what job you do, who you marry, how many children you have. You have no belief in your ability to control your future.”

Human weakness—and excessive regulatory oversight—prevents commitment between the sexes. The letter writer begins every proposal of marriage with a declaration of love, sends expressions of passion, receives opposition from the girl’s father and work unit, attempts to transfer residency permits, negotiates a brief affair with a third party, encourages a reconciliation, and organizes the final breakup. He himself longs for a woman of flesh and bone. The word love is permitted, but love itself is scarce. Laughter draws the attention of the police. If women are assaulted, either the size of their breasts or their tight skirts are to blame. In the wake of a riot following a gang rape, people walk in groups of four.

When empathy disappears, sexual freedom becomes a tool for subjugation. The actress sees the vagina as “a depraved dance floor” and the sexual act itself as “horrifically obscene.” The blood donor says, “We delude ourselves into thinking love will make us happy.” The dog complains that humans should not be allowed to love, that all they really want is to eat, have sex, and go shopping. The emotions of the novel swing from hysteria to melancholy, from the surreal to the most mundane aspects of survival in an absurd world.

By going even further, by placing the narrative inside the brain of Da Wei, a student gravely wounded in the Tiananmen Square massacre, Beijing Coma defines the posthuman situation. The damage to his hippocampus, which connects the brain to memories and emotions, has left him in a vegetative state, unable to move, touch, or see. As the patient lies comatose for a decade, Ma uses flashbacks to allow the reader access to the student uprising as Da Wei experienced it. While in his coma, Da Wei hears the everyday happenings around him, layering the present onto the past.

This account of the student uprising merges revolutionary fervor with romantic love and sexual passion. Da Wei has three loves during his twenty years of health. Inside his coma he relives them. “My brain releases into my bloodstream the mixture of phenylethylamine and serotonin that is known as love.” When Da Wei hears the list of demands for freedom of thought, speech, and an end to one-party dictatorship, he says to his friends, “I’d be happy if they just granted us the right to have relationships while we’re at university.” To fight is to love. Inside the tents of Tiananmen Square, couples embrace and discuss policy. A rock star sets up a stage.

Students criticize Mao for their unhappy childhoods. “Ma destroyed the traditional family system so we’d all have to depend on the Party, ” one says. Another adds, “As soon as we were born, our parents handed us over to the Party and let it control our lives.” However, once the guns fall silent and the crackdown begins, the parents will have to care for the victims.

After the revolution, the Mothers of Tiananmen Square organized the work of mopping up the blood.

Ma dedicates this book to his mother. After the revolution, the Mothers of Tiananmen Square organized the work of mopping up the blood. Da Wei’s mother protects and cares for her son in the years following his injury, welcoming visits from friends and lovers, keeping his wooden body clean and nourished. Some survivors marry or flee abroad to study and work in England or America. Some go insane, some die in prison or by suicide. The police visit often, complaining that Da Wei has not awoken so they can question and imprison him. His mother sells one of Da Wei’s kidneys to fund his care. She tells him he’d be better off dead but keeps nursing him. The novel is as much a paean to motherly love as it is to the love and friendship among the rebels who fought and died for a dream—that others could live without fear.

When The Dark Road opens, the subject has turned from fighting for freedom of thought to fighting for freedom of conception. Peasants are rioting against the police and running for their lives from family-planning squads. The novel is told from Meili’s point of view. She, her husband, Kongzi, and their daughter, Nannan (Ma gives her his daughter’s name), leave their village just as the squads are dragging off women to be sterilized. Since Meili is illegally pregnant with their second child, they have become family-planning fugitives. Meili fears a forced abortion. Kongzi insists on a male heir to carry on the Kong family name that stretches back seventy-six generations to Confucius. Nannan wants to grow up in “a country that doesn’t kill babies.” Because of male preference, girl babies are particularly at risk. Vaginas belong to husbands, wombs to the state. A sign on a wall reads, “After a first child, IUD; after the second, sterilization. Pregnant with a third or fourth? Then the fetus will be killed, killed, killed!” Police stop an attempt to organize a Fertility Freedom Party and send the leaders to jail.

Ma seamlessly connects the One Child Policy to the growing problem of pollution, from factories at home to e-waste from abroad. As the migrants’ boats flow north, they breathe in toxic fumes from garbage-strewn channels. Officers spot the heavily pregnant Meili from shore and take her to an abortion clinic. The family’s journey ends in Heaven, a town so deadly its inhabitants are sterile. One neighbor declares, “This is a country where everyone is poisoning each other. It’s a game—whoever dies first, loses.” The new wealth made from recycling waste brings no satisfaction. Kongzi must return to Confucius, his ancestor, for wisdom. The Analects, which encourage respect for learning, honoring parents, caring for children, and leading a virtuous life, have never been so timely. After this book was published, the government denied Ma permission to travel to China.

Ma seamlessly connects the One Child Policy to the growing problem of pollution, from factories at home to e-waste from abroad.

Unlike his other novels, China Dream’s central character is an unsympathetic official, Ma Daode, director of the new China Dream Bureau. Fat, toadlike, corrupt, predatory, and lascivious, he would be an ugly caricature except for another Ma Daode of the past bottled up inside his mind struggling to emerge. That Ma Daode was a sent-down boy of fifteen when he lived with the peasants in their village, joined the Red Is East faction of the Red Guards, rejected his parents, and went on a murderous rampage during the “violent struggle” period of the Cultural Revolution. He sees his present role as brainwashing everyone’s memory, replacing it with the China Dream, soon to be a Global China Dream, a nirvana of collective thought via a microchip implanted in the brain.

He hosts a China Dream Golden Wedding Anniversary Banquet and carries on numerous affairs by text as well as in person. His texts are dirty jokes, the sex abusive and strictly transactional, with plastic-faced automatons. All the while, during sleeping and waking nightmares, Ma Daode relives his role in the brutal excesses of the Red Guard factions, seeing visions of men he murdered and the death of his first love. He resorts to a memory-cleansing potion from the land of the dead, but certain memories can never be repressed or forgotten. In Ma’s latest and most pitiless satire, he estimates the human cost of the Cultural Revolution. The price of forgetting the past is forgetting how to love.

The price of forgetting the past is forgetting how to love.

Taken together, the attitude toward love and sexuality in Ma Jian’s fiction varies from lyric to mocking. At first his graphic accounts of sexual abuse are balanced by tenderness. With each succeeding novel, love diminishes and sex grows more mechanical. As the bitterness of his critique deepens, his hope for change dims, and the possibility of love fades.

Center Valley, Pennsylvania

Three Questions for Ma Jian

What recent book has captured your interest?

This last year, I have been reaching not for new books but for ones I’ve read many times before: works of Dostoevsky, Kafka, Camus, and the philosophers of ancient China.

What outside the realm of literature has drawn your attention of late?

The protests in Hungary, France, and Venezuela; the chaos of Brexit; President Trump and his wall; the horrifying internment of a million Uighur Muslims in China’s Xinjiang Province.

What current writing projects do you have underway or have planned for the near future?

I am working on two books: one fiction, one not. I hope to finish them soon in the writer’s shed that I’m building for myself at the end of our garden.

February 2019

Translated by Flora Drew