Hong Kong Food Runes

Infiltrating Hong Kong’s noodle stalls, Lian-Hee Wee investigates the quick, mysterious writing used by waiters on order slips.

Nobody knows I’m a fraud. No one here knows where I live, but they assume I live nearby—every evening with my punters’ guide, a black notebook, and a dozen bottles of beer. Like an unassuming creeper, I leisurely slot myself into taking food orders for customers when the noodle-stall keeper does not have enough hands, until eventually I’m asked to simply open the till for change.

The kitchen lights are dimmed by the steam and smoke, just as eyesight is faded by sweat from the brow. The several daai paai dong1 stall owners here and their employees are not totally illiterate. The quasiliteracy, however, compels them to live along the margins of the law—licensing being predicated on bureaucratic forms and notices too difficult to process. Frustration must therefore be assuaged by stolen puffs at cigarettes when health officials are not in sight. Steam, smoke, heat, and poverty-induced or light-deprived murkiness all conspire to militate against efficacy in the communication of customer orders.

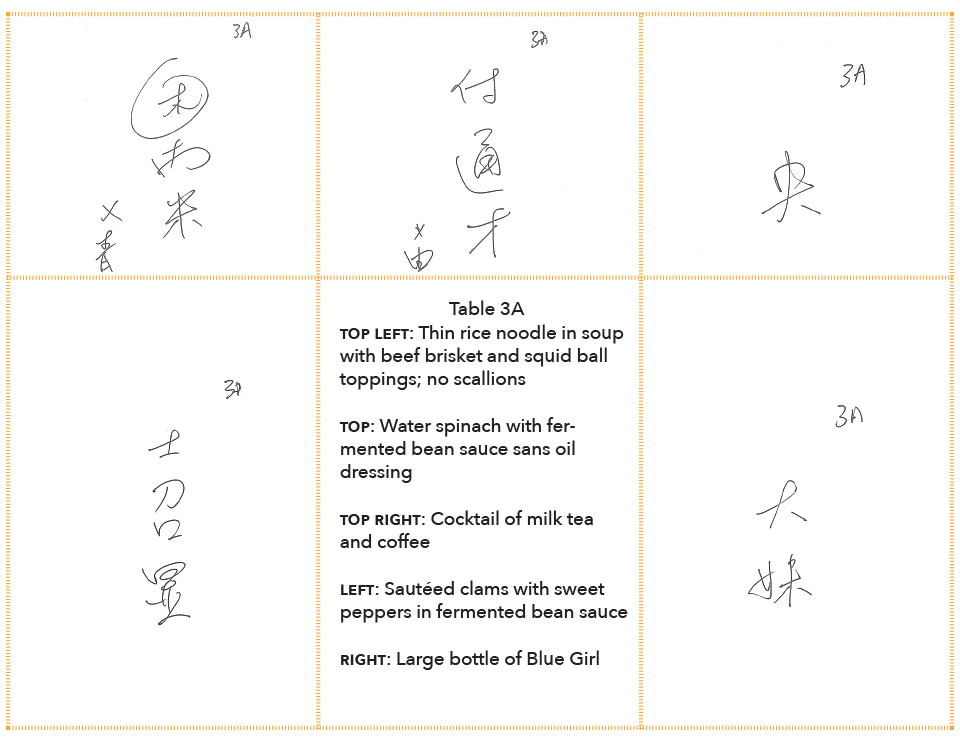

An uppity lady and her companion have irrationally decided to come here. She rattles off under tissue-paper-muffled breath, “Thin rice noodle in soup with beef brisket and squid ball toppings, no scallions. A side of water spinach with fermented bean sauce, no oil dressing. A hot cocktail of milk tea and coffee!” She plants herself at what we have designated among ourselves as Table 3, intended to seat four people. I shall indicate hers as Table 3A, so that two others may sit there as a separate party when all the tables are occupied. Giving me about three seconds to write her order down, her companion suggests, with but a tiny hint of patience alongside pleasant condescension, that I go to the adjacent stall to get him sautéed clams with sweet peppers in fermented bean sauce and a large bottle of Blue Girl.2 On my order slips, each measuring 2 by 3 inches, the orders look like this:

Each slip is slotted in between my fingers according to where each dish will be prepared. These pieces of paper accumulate as I meander past other tables squealing for their orders too to be scribbled. Customers do not care if you work for one stall or another, nor are they bothered by how the used dishes from different stalls need to be sorted and returned. Daai paai dong wait staff, and various cashiers, do have to care, do have to be alert.

Logistics vary slightly between the daai paai dong, the caa caan teng, and the other eateries that define the Hong Kong gastronomic experience. But the runic writing on the order slips remains the same, as I discovered during my several infiltrations into different establishments—even to some in New York City and San Francisco Chinatowns. The runic writing is as mysterious to many Hongkongers as they are familiar to them. This quick script is no secret; we’ve all watched waiters scribble across their wafer-thin pads, but what waiter’s got the time to explain the squiggles? In Hong Kong, any time is mealtime, and mealtime at its peak typically entails six people, possibly strangers, at a table three feet in diameter. In a space measuring one hundred square feet, expect twenty to twenty-five customers at any given time if you hope to cover your rent. Why, just yesterday, my friend, a chef at a small eatery of the above dimensions was paying HK$35,000/month for rent—this notwithstanding that each customer’s bill averages only HK$50.3 With utilities, salaries, ingredients, and other sundry costs, that tiny shop must take in HK$8,000 a day to survive—i.e., 1,600 daily orders.

Even a small noodle stall will have at least five types of noodles, twenty toppings, various options for sauce, and other add-ons that allow anyone to choose from some 1.6 million combinations.

“Mud doe gum tsui bin, bin yau yan bei min?”4 is a Cantonese proverb, nearly a creed, making jerks out of those whose egos are in want. At the local eateries, this is manifested through the illusion of customized orders for a paltry price. Even a small noodle stall will have at least five types of noodles, twenty toppings, various options for sauce, and other add-ons that allow anyone to choose from some 1.6 million combinations. And this just for one person’s noodle meal, not counting drinks. The complexity of choice is what’s captured in the little slips. The runic writing is Hong Kong’s Kitchen Shorthand. It is terse; easy for kitchen staff to read; yet clear enough to distinguish between a myriad of possibilities.

No, there aren’t a million different symbols. There are principles underlying these runes. In the first slip above, the 木 is a Chinese character meaning wood, which is nearly homophonous with “ink,” itself encircled so that it stands for ink ball (→squid ball). 米 is the character for “(uncooked) rice,” which is what is used to make thin rice noodles. The strange cap above it is the first few strokes of 南, homophone for brisket. The ✗ in the bottom is a negator, and 青 means “green” (→scallions). The other slips contain similar cryptography that speaks of the ingenuity of maximizing minimum literacy. 央 in the third slip is an extraction from the second character of 鴛鴦 “Mandarin ducks,” which are romantically believed to come in monogamous pairs. The eroticism of stirring one fluid into another to make a blend out of two beverages injects an unspoken humor to mitigate the dread of this onerous work. By combinations of simple homophonous characters, and by extractions of distinctive ideographic shapes, a semiliterate waiter can speedily write what remains remarkably legible to the similarly semiliterate kitchen. In my case, shuttling between stalls in a daai paai dong, I must be able to produce unambiguous order chits for what likely amounts, without exaggeration, to potentially about 10 million items. So what is real literacy anyways?

By combinations of simple homophonous characters, and by extractions of distinctive ideographic shapes, a semiliterate waiter can speedily write what remains remarkably legible to the similarly semiliterate kitchen.

A mother chides her child, “I dun noe how to read this, dun ask! You want to work as waiter in daai paai dong meh?” She says this to the boy who enquires about the scribbling on my pad. I smile and turn to other duties. Within earshot I hear in a lower, earnest tone, “If you dun study harder, may be you wan be like him?” A nonchalant look hangs on the faces of the waitstaff around me, apparently in resigned agreement. When there are brief moments of pause, with tending to but a handful of occupied tables, some of us chat as we steel ourselves for the next tidal wave of customers. We talk about the weather, interesting people, annoying people, and how hard it is to survive. Hardly anyone delves into the personal. What did you do in the past? What do you hope for tomorrow, for the future? To the former, the answer is often “same as this,” as if it is a lowly caste birthright that nullifies dreamy ambitions or happy childhoods past. A criminal past is not impossible, but unlikely. Poverty, not laziness, is what fuels their continued difficulties, which explains why the answers to the second question rarely extend beyond “Tomorrow, you mean? Oh, tomorrow is race day. I go bet on horses.”

Tomorrow, kitchen stenography will go the way of the Futhorc runes—forgotten with much else of old Hong Kong foodways.

Author’s note: Dedicated to the people whose lives I infiltrated from 2000 to 2008 for this study. They must remain anonymous. Thanks to Jason S. Polley and Kum-Hoon Ng for many helpful comments.

1 Literally, a big row of stalls in Cantonese, a hawker center.

2 A local “imported” beer.

3 Data from an actual shop in Kowloon, Oct. 8, 2018. HK$35,000 converts to approximately US$4,500.

4 Word gloss: Everything also easy-going, where have person (to) give (you) face?