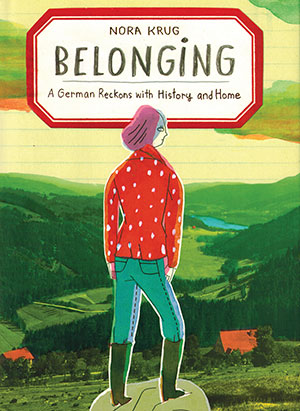

Belonging: A German Reckons with History and Home by Nora Krug

New York. Scribner. 2018. 288 pages.

New York. Scribner. 2018. 288 pages.

Revisiting and then capturing the past, especially a historical past, always requires an exercise in imagination. Moreover, when the imagination has been informed by the combination of a heinous historical event, family lore or lies, the burdens of guilt, and the limits of exoneration, the task is almost impossible. It is just this impossibility that Nora Krug takes on in Belonging, her difficult, provocative, and ultimately moving graphic memoir.

Born in Karlsruhe, Germany, in 1977, well after the war, Krug now lives and teaches in New York City. Nostalgia for home is common in expatriates, and Krug is no different. The image with which she opens the book is a drawing and explanation of a Hansaplast, the German bandage with which her mother patched her scraped knees. It is the best of bandages, covering the injury and guaranteed not to come off until the wound is healed, but it hurts like hell to get it off to examine the scar. There is little subtlety in this apt metaphor for Krug’s search into the history of her family and its potential Nazi past. In the course of this jam-packed scrapbook of a memoir, she rips off bandages, uncovers some truths, and raises many questions, some of which, necessarily, go unanswered.

It is an amazing quest, and a brave one, to go from a comfortable perch in New York, married to a half-Jewish man, to seek out the Nazis in the closet. But an encounter with a concentration camp survivor early in Krug’s time in New York stirred the need to understand her homeland, her family, and her Heimat, the complex German concept of home and familiarity that runs throughout this book and is the title of the German version.

With a dazzling array of visuals and text styles, Krug traces the lives of her paternal and maternal families through photographs, drawings, documents, and pieced-together family remembrances. Her style is eclectic, combining comic-book techniques along with painterly gouaches and illustration. In one instance, she illustrates the imagined responses of her maternal grandfather to the question of where he was on Kristallnacht during the burning of a synagogue directly across the street from his office. His four possible answers are illustrated in an “a” through “d” set of panels and range from his being somewhere else to being an observer to being in some way complicit and approving. She doesn’t know, can never know, the whole truth, and the awfulness of that uncertainty drives her to try to uncover more information.

In her quest for an unholy grail, Krug creates not only a truly affecting memoir but also a rather remarkable lesson for a world that will soon be without any firsthand witnesses to the Holocaust. Survivors are dying out while historians are still uncovering new information and keeping the research alive. But such singular journeys and testimonies as Krug’s will keep readers, and especially younger readers in the case of a multifaceted graphic memoir, engaged with history, both individual and societal. This is the kind of work that truly questions the ways in which leaders and movements may or may not coerce or co-opt their constituents, some unwitting and some not so innocent.

The most effective memorials are the ones that resonate with contemporary readers. That is exactly what Belonging does. This is an important work that brings history to life via one family in a personal way, perhaps the only way in which future generations will be able to relate to the Holocaust.

Rita D. Jacobs

New York City