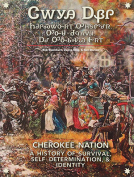

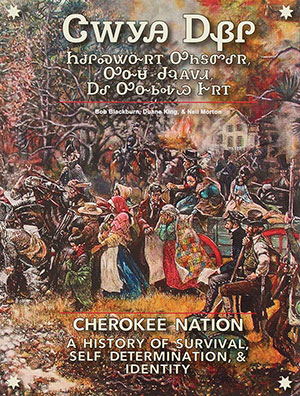

Cherokee Nation: A History of Survival, Self Determination, and Identity by Bob Blackburn, Duane King & Neil Morton

Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Cherokee Nation. 2018. 278 pages.

Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Cherokee Nation. 2018. 278 pages.

The team behind Cherokee Nation is a veritable powerhouse. Bob Blackburn, executive director of the Oklahoma Historical Society, has roots in the Cherokee Nation. The late Duane King was a nationally known expert on Cherokee history, founding editor of the Journal of Cherokee Studies, and former director of the Cherokee Heritage Center. Neil Morton is the longtime director of education for the Cherokee Nation. In addition, design, graphics, and the use of the Cherokee syllabary throughout the book were the work of noted Cherokee artist Roy Boney, who is the director of the Cherokee Nation language program.

This comprehensive history of the tribal nation is the first to undertake the task since Billy Jones and Odie Faulk’s Cherokees in 1984. Since then, major changes have occurred in the Cherokee Nation, all of which are covered here.

The book traces Cherokee history from prior to contact with Europeans to the present moment. The work is panoramic and kaleidoscopic, taking in the full sweep of the history of the Cherokee Nation. In fact, the authors strive to tell the complete story, yet, at 278 pages, at times it seems like a rush through a very eventful history. This, however, is a quibble. Make no mistake: this is an important and timely book.

At the time of first contact with Hernando de Soto in 1540, the Cherokee covered parts of what are today parts of eight states. The Cherokee sided with the British during the Revolutionary War and suffered the destruction of their town by the colonial army. What follows is a story of prolonged dispossession, culminating in removal from their remaining homelands and the genocidal Trail of Tears to a new home in Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma).

The final dispossession of Removal was followed by a reconstruction of their government and the gradual healing of the divisions that fractured the nation until after the American Civil War. No sooner had the war ended than dispossession at the hands of the federal government resumed, reaching its final conclusion with the dissolution of their sovereign government in 1906.

This, however, is not a story of unremitting tragedy. After 1906 the Cherokees worked unceasingly to restore their sovereignty until self-government was restored in 1971. This is a story of resiliency and success. Since the Jones and Faulk book, the Cherokee Nation elected Wilma Mankiller as the tribal nation’s first female principal chief. She brought financial stability to the nation. The advent of casino gaming brought expanded opportunities and economic success. Informative sidebars slow the story to give profiles of significant figures from Beloved Woman Nancy Ward to W. W. Keeler, the first principal chief after the resumption of the government.

Boney richly illustrates the volume with historical photographs and paintings and rich contemporary works by Cherokee artists, including stunning cover art by Daniel HorseChief. One wishes he had included more of his own work besides the single portrait of a Cherokee codetalker. (He also produced the helpful maps throughout the text that make history visible.)

In sum, Cherokee Nation is an important tale well told.

Jace Weaver

University of Georgia