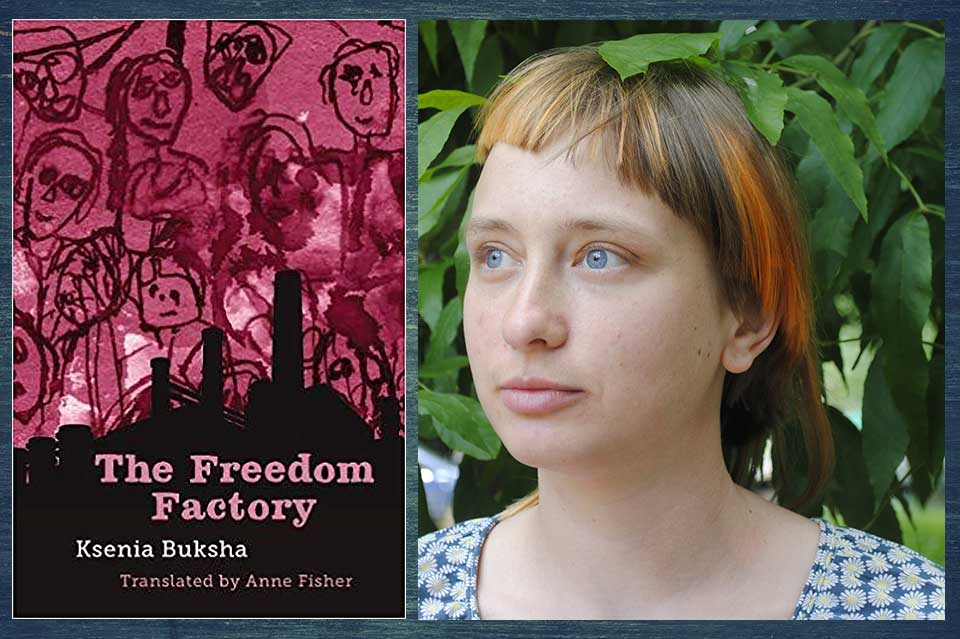

What We Translate When We Translate Literature: On Ksenia Buksha’s The Freedom Factory

With apologies to Raymond Carver, what do we translate when we translate literature? What are we doing? And how do we do it?

There are books upon books that answer this question. For Walter Benjamin, translation is a theological or even metaphysical act; for Susan Sontag, translation is an ethical act; and for Lawrence Venuti, it is an act of resistance, or at least remonstration. We have Cicero’s practical, yet mystifying prescription—render meaning by weight, not by volume—and we have Étienne Dolet’s blunt proscription: “those who endeavor to translate line by line or verse by verse are fools” (don’t tell Nabokov).

Translation is an aesthetic act in which the translator tries to replicate the artistry of the original, providing the reader of the translation with a similarly rich and powerful aesthetic experience.

I am still seeking my own translation mantra among the thickets of theory; the closest so far is Peter Cole’s arch “thou shalt not kill.” But I am also moved by Schlegel’s comment on faithfulness to your author: fidelity is “making the same or a similar impression, for impressions are the essence of the thing.” To me, this “impression” is another name for the reader’s aesthetic experience: translation is an aesthetic act in which the translator tries to replicate the artistry of the original, providing the reader of the translation with a similarly rich and powerful aesthetic experience. In other words, wherever the original writing is so beautiful—or moving, or funny—that it causes the reader to read a line aloud to the nearest warm body, or write a note in the margin, or dog-ear the page, or keep reading past a reasonable bedtime, the reader of the translation will ideally do the same.

This is easier said than done. We all know that beauty is subjective, as are readers. And translators. But it is a challenge and a joy to work with texts that provoke complex aesthetic responses, which is just what Ksenia Buksha’s novel The Freedom Factory does. It ranges from industrial shop-talk to absurdist verbalizing to dream sequences; it has found dialogue, parodies, and snatches of popular songs; inner monologues are interspersed with official Soviet voiceovers; and through it all we have Buksha’s telegraphic style, which makes you work just a little harder as a reader, and a lot harder as a translator bound to render Buksha’s hints, intimations, and references without overexplication or bloat.

Of all the things I enjoyed picking at, dancing with, and courting in this translation, one of the best was the beauty of Ksenia Buksha’s prose.

Of all the things I enjoyed picking at, dancing with, and courting in this translation, one of the best was the beauty of Ksenia Buksha’s prose. She’s a poet and artist as well as a fiction writer, and many of her lines spring out at you, driven by the coiled sonic structure inside. Here’s a passage from chapter 29 about the rough times the factory endures after 1991, when it almost closed down and the once-mighty river of workers pouring down the street into the factory gates has gone dry. Read it out loud, and see what you hear:

Иссякая, течёт по утрам ручеёк по улице Волынкиной. Следы остывают. Пустынно в парке у пруда. Пустынно на заводском дворе.

I was taken by the beginning of the line, иссякая течет по утрам ручеек: the swaying alternation of a (ah) and o (oh) vowels is arresting. That lovely, lilting sentence ends, to be followed by three short, sharp sentences that pick up the almost guttural letter ы (ih) in Волынкиной and pound it repeatedly: следы остывают, пустынно в парке, пустынно на дворе. Then there’s the repetition of the word пустынно, and the echoing of its initial plosive in other short, sharp words: в парке, у пруда. So there’s a lot going on here with patterns of vowels and consonants, and with the changes in those patterns, and it was important to at least approximate that.

First thing to do is just get the sense on the page, throw down that first glob of clay, get out a literal translation or “crib”:

In the mornings, a little stream flows along Volynkina Street, drying up as it goes. Its traces are growing cold. It’s empty in the park by the pond. It’s empty in the factory courtyard.

Okay, so far so good. That’s something. But now I need to shape it, create some sonic patterns. So I fiddled around, and came up with this:

Each morning, an eerie, dwindling rivulet creeps down Volynkina Street. The tracks of working stiffs’ feet are fading. The park by the pond is derelict. The factory courtyard is derelict.

Not too bad; it has a nice sound palette with the repeated long e’s and short i’s, has some nice alliteration going on. But I was still lukewarm about it, so I flagged it with a note about maybe being able to do a little bit better. I returned to it after letting it sit for a few months and saw that the rhythmic alternation of vowels worked fine without the word “eerie,” because even without it we’ve still got lots of long e sounds: each, morning, creeps, street. The eerie is appropriate, it fits, but it overexplains; and that is not how Ksenia writes. She shows you that it’s eerie, she makes it feel eerie, but she doesn’t tell you.

And then I decided that having to come up with the phrase “working stiff,” just to carry on the short i from “dwindling rivulet down Volynkina,” was too clunky, too forced. And then I ended up questioning “derelict” for пустынно here. We can have derelict buildings in English, but does “derelict” apply to spaces that are open and mostly empty anyway? I started to feel that replicating the repetition of ы was causing odd collocations and making me add length without getting the corresponding “aesthetic ROI.” I came up with something that dialed back on the soundplay in favor of Ksenia Buksha's other stylistic elements, like her compactness and striking imagery:

Each morning, a dwindling rivulet creeps down Volynkina Street. Its traces are fading. The pondside park is vacant. The factory courtyard’s a blank space.

I lose the exact repetition of пустынно: instead of the repeated “derelict” I use two different words, “vacant” and “blank space.” I do have assonance there, though. Plus, “vacant” and “blank space” call back sonically to the words “traces” and “fading,” so there is also an echoing between sentences like there is in the original. And overall, it’s tighter (38 syllables as opposed to 47) and it explains less. This is better.

Here’s another example of a passage from the novel that I found beautiful, and what I did to try to re-create it. This is from the wistful chapter 34, where a young director does his best to allow a retired engineer to keep being part of the factory.

Наступает ночь, чёрная и ветреная, как и прошлая ночь. Ветер воет в дымоходах и вентиляции, свистит в скважинах. Черный цвет заливает всё. У чёрного множество оттенков. Блестящий чёрный и прозрачный, густой и жидкий чёрный.

Here you have the repeated round o (ночь, чёрная, прошлая, ночь, воет, дымоходах, чёрный, всё, чёрного, множество, чёрный, густой, чёрный); we have the repeated word чёрный; we have assonance on the letters н and в; and we have a concentration of sibilants and plosives in the last sentence. There’s a lot packed into this; it’s aesthetically dense.

Here is a basic English translation, essentially a crib, of this passage:

It’s coming on night, black and windy like last night. The wind howls in stovepipes and vents, it whistles in cracks. Black color pours over everything. Black has a multitude of shades. Shining black and transparent, thick and thin black.

No noticeable repetition in this word-for-word trot. How do I bring this up to the aesthetic density—i.e., the beauty—of the original?

The key words in the translation are чёрная ночь, which mean “night” and “black,” and you can't miss the big fat round o’s in them. I really wanted to pull that out and play on it the way the original does. Unfortunately, “black” and “night” don’t share a vowel the way черная ночь does. So I chose one sound: the diphthong ai from “night.” I needed some alliteration, too, so I started with наступает ночь = “Night draws on,” choosing “draws on” for наступает to produce two n’s in my opening phrase the same way that наступает ночь has two н’s. Then I wrote down the vowel sounds from those words: EYE AH AH. Okay, there is my sound palette; now to choose words accordingly. Now on to the thesaurus page of dictionary.com to look at the synonym clouds, scanning all the columns for words with these sounds, EYE and AH. Not too hard: “cries” and “whines” instead of “howls” and “whistles.” Aha, but now what do I do with у чёрного множество оттенков? To replicate this effect of all those long, open o’s, I needed something with the meaning of множество (multitude, many) that also has the sound EYE from my own key word, “night.” This is where the brainstorming comes in: night is rife with, is comprised of, has diverse throngs . . . but I didn’t like any of them. Too wordy. So I recast the image, freed myself from the meaning, so I could use different lexical tools to create a similar effect. I chose the actual word “eye” and came up with this:

Night draws on, black and windy like last night. The wind cries in the stovepipe and vents, it whines at all the windows. Everything’s awash in the color black. Black offers the eye many shades. Brilliant black and transparent black, thick black and thin.

This has assonance on the diphthong ai/eye, it has alliteration on the letter w, it has the initial vowel of “awash” and “offers” linking two sentences, it has lots of plosive b’s, t’s, and k’s in the last sentence. That’s a level of aesthetic density I can live with.

And then it’s on to tackle the next beautiful sentence.

Translators will always be inadequate to the task of translation, but we will always translate anyway.

Translators will always be inadequate to the task of translation, but we will always translate anyway. It reminds me of Khodzha Z from The Freedom Factory, when he returns to the factory after a long absence and sees the love of his life, M. It’s impossible to speak to her, just as it’s impossible to translate; but speak—and translate—we must:

Oh my goodness gracious, it’s Khodzha! Z blinks. He’s blinded. Forget “to heck with her.” His mouth is dry. Her eyes are even greener. Z tries to speak: M. He takes off his glasses, wipes them. He rubs his bald spot. He stands up and tugs his jacket down. Easy now, need to say it just the right way. My dear M, they haven’t changed you a bit.

Crawfordsville, Indiana