Contemporary Faces of the River Merchant’s Wife

T. S. Eliot, in 1928, famously called Ezra Pound “the inventor of Chinese poetry for our time.”1 Eliot was referring to Pound’s renditions of fourteen Chinese poems in Cathay (1915). This remark may for some seem arrogant and orientalist, a term Edward Said would half a century later coin to critique the West’s at times self-serving constructions of the East. That said, many consider Cathay to be responsible for first sparking an interest in classical Chinese poetry in the West. Eliot Weinberger, for example, believes that “Cathay had set off a small landslide of Chinese poetry translation.”2 Ten decades on, this fascination shows no sign of abating, as is indicated in a 2016 article entitled “Tribunals of Erudition and Taste: or, Why Translations of Premodern Chinese Poetry Are Having a Moment Right Now,”3 in which Cathay is discussed.

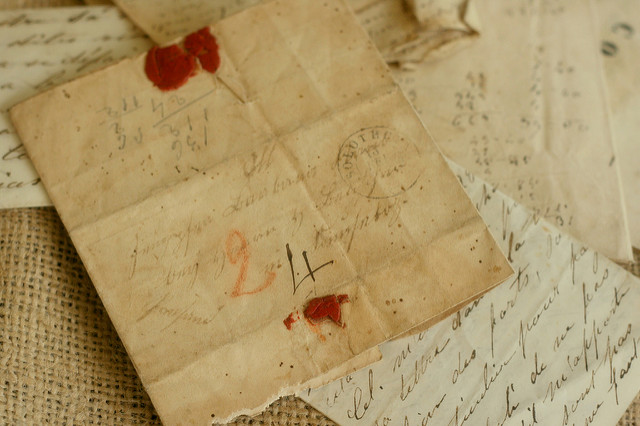

The circumstances of the publication of Cathay have been recounted many times. Pound, who knew little Chinese, if any, wrote the English versions of selected poems by the renowned Tang poet Li Bai by consulting transcribed notes made by the late Ernest Fenollosa, who had in turn been helped by Japanese scholars. One of the poems from this slim collection that has received much attention is Pound’s version of Li Bai’s first poem in “Changgan Xing” (长干行), retitled as “The Merchant River’s Wife: A Letter.” Despite the availability of other more “accurate” translations,4 Pound’s work has played an important role in the popularisation of the poem in the West.

Adaptations of and homages to Li Bai’s poem, filtered through Pound’s interpretation, can be found in English-language texts set in diverse settings, attesting to the poem’s cultural commensurability and Pound’s lingering influence in introducing the Chinese poem to a wider readership.

Although set centuries ago in a city in eastern China, Li Bai’s poem expressing the love and longings of the faithful and determined wife of a travelling trader has continued to resonate in contemporary times. Adaptations of and homages to Li Bai’s poem, filtered through Pound’s interpretation, can be found in English-language texts set in diverse settings, attesting to the poem’s cultural commensurability and Pound’s lingering influence in introducing the Chinese poem to a wider readership. In the following, I will investigate three examples of such English-language adaptations.

* * *

The female poet Luca L.’s “Letter to Ru Yi, the River-Merchant’s Wife” is a response poem written from the husband’s perspective. As such, it reverses the gender roles in the Chinese source text and Pound’s version, in which a male poet “cross-dresses” as a woman by donning the voice of a yearning wife.

Letter to Ru Yi, the River-Merchant’s Wife

by Luca L.

A response to Ezra Pound’s “The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter,” in turn based on the first of Li Po’s “Two Letters from Chang-Kan”

In the evening the boats and people leave.

The river stills. I see the moon in it

and think of you – like you

it keeps one face hidden.

(When you read this you will protest this,

that much I know of you.)

We spent two summers together, one in indifference,

the other approaching love. Even then

you vanished in moments, becoming dark again;

sometimes I flashed in anger at your elusiveness.

When I left you, the insects were humming in the sorghum

and you were squinting at me through dense bars of sun.

That morning you tied a charm around my neck,

wood-coloured and smelling of incense, your gaze

as fixed and full as on our first playdate,

the adults plotting the stars behind us. We could not

see their map, so we focused on the flowers and plums,

the things we could hold in our hands.

Now I go upriver and you clean house.

Sometimes I glimpse that starry map,

and wonder how it looks

from your place at the end of the river.

The string around my neck broke yesterday;

I’ve replaced it with a new one.

I expect I shall be back by June,

but you can never tell with these currents.

(Issue 22, Cha)

L.’s poem is tender and gives the silenced husband in the original poem an opportunity to also express his love for his spouse. This is reminiscent of A.D. Hope’s “His Coy Mistress to Mr Marvell,” a cross-temporal response to Andrew Marvell’s carpe diem poem “To His Coy Mistress.” Hope’s poem, narrated from the perspective of the “coy mistress,” imagines the unnamed woman in Marvell’s work to be sassy and able to see through nonsense. She is not so easily wooed and won over by a poet skillful with words. Hope, a male writer impersonating a female voice, provides an entertaining and feminist rebuttal to Marvell’s classic poem.

The gender politics in L’s poem is even more complex. Li Bai’s poem may have been composed following “a tradition for early Chinese poets to write about the complaints or longings of traveling merchants’ wives.”5 This form of gender-crossing may also be interpreted as an example of the exclusion of women from educated social and political societies in pre-modern China. According to Paul F. Rouzer in Articulated Ladies: Gender and the Male Community in Early Chinese Texts (2001), the world of the male literati rarely admitted women, and even though some women did enter some texts, this was either through “male adoption of female behaviour,” like in Li Bai’s poem, or by learning to imitate male language and express male concerns. In L.’s poem, we see a female poet from the twenty-first century writing as a merchant addressing his wife and revealing his vulnerability—a reversal that, given the history of the representation of gender and desire in early Chinese texts, is particularly interesting.

* * *

While Luca L.’s poem is presumably set at the same time as Li Bai’s original, in Alistair Noon’s “The Expat’s Partner: An Email” the Tang poem is updated to the contemporary world.

The Expat’s Partner: An Email

A hundred miles from swells and tides,

planks flotsam a building site.

Trees practise for spring with first buds,

though snow survives in dumper truck ruts.

Shadows of girders lattice the light.

The beaked pick at dark tufts.

At twenty we snogged in a low-lit squat bar,

cracked glass guitars and dirge vocals a serenade,

one-mark pilsner our aphrodisiac.

We came back for the next decade.

This year you flew to a contract with change,

to a shift no longer in sync with mine.

Jets sobbed above my head.

They banked into sunshine, my feet

almost floated from the ground.

Across these months we’ve coordinated calls,

your dawns my dusks,

tapped out alphabets along deep-sea cables,

like voices down halls,

clinked no bottles on chafed sofas.

Tell me the arrival time, the connecting flight,

I’ll wait with my hands on the trolley brake.

(Issue 2, Cha)

Noon’s poem, subtitled an “email,” is a conscious update of Pound’s “letter.”6 In this wonderfully poetic “email,” a lover is writing to an absent partner, the “expat” of the title—again, a reference to a more modern phenomenon: globalisation and the convenience of international travel.

In the first stanza, the persona appears to be describing a late-winter scene from a slightly ambiguous perspective. It is clear, however, that spring is anticipated: “Trees practise for spring with first buds, / though snow survives in dumper truck ruts. / Shadows of girders lattice the light. / The beaked pick at dark tufts.” The reader later realises these early lines also foreshadow the return of the partner—the poet uses the traditional trope of associating spring with returning love. While the trees practise for spring, is the persona also practising for the lover’s homecoming?

In the second stanza, the persona recollects moments from their early relationship. We are shown nostalgic flashbacks of a bohemian romance, possibly in Germany: “At twenty we snogged in a low-lit squat bar, / cracked glass guitars and dirge vocals a serenade, / one-mark pilsner our aphrodisiac.” This young love proves to have legs, however: “We came back for the next decade.” This line has a nice double meaning: the lovers are not only starting their second decade together, but have they also come back to the locale where their love germinated?

Soon, we see a fully mature relationship, and the formerly bohemian atmosphere has changed to a pragmatic one. The partner is about to become an expat by pursuing a career abroad: “This year you flew to a contract with change, / to a shift no longer in sync with mine.” To the persona, this new arrangement does not seem to be an easy one. There is a sense of losing touch: “Jets sobbed above my head. / They banked into sunshine, / my feet almost floated from the ground.” With the absence of the lover, the persona seems to suffer from not only uncertainty but also rootlessness. Or perhaps the speaker is being lifted towards the faraway lover, attracted by the magnetic pull of their affection.

The reader is never certain whether these feelings are reciprocal or whether the lover will really return. An email, like a letter, remains one-sided unless answered.

Later, we are shown glimpses from this long-distance relationship, the routine of absence: “Across these months we’ve coordinated calls, / your dawns my dusks, / tapped out alphabets along deep-sea cables.” But the communication of the separated is imperfect; they speak to each other “like voices down halls.” And there is of course the inevitable loneliness and longing. The couple have not shared any real moments of intimacy, have “clinked no bottles on chafed sofas.”

And yet in the final stanza, there is the possibility of the reunion that was foreshadowed in the opening lines. With the assurance, practicality, and unquestioning devotion of love, the persona finishes the email with the following: “Tell me the arrival time, the connecting flight, / I’ll wait with my hands on the trolley brake.” In Li Bai’s poem, the wife agrees to meet her merchant husband two hundred miles from their hometown.7 The promise of the protagonist in Noon’s poem to wait for the returning lover at the airport is less extravagant and speaks to the changed world where mechanical machines fly in the air—unimaginable in Li Bai’s days. In both the Chinese original and Noon’s adaptation, there is confidence in the stability of the relationship and a promise taken for granted in this conclusion. But the reader is never certain whether these feelings are reciprocal or whether the lover will really return. An email, like a letter, remains one-sided unless answered. Is the persona actually making concrete plans to pick up his or her partner? Or are the final lines a plea for the lover’s return?

* * *

Finally, I would like to look at a poem that responds to and updates the Merchant River’s Wife in a more oblique way, even though traces of the source text are still recognizable.

Ghost Husband

Uncountable miles away your cells undergo

respiration in the air of a land I do not know.

Strange tones, alien vowels ring

in your ears like wood striking bronze.

New words permeate your dreams but I hear only

fragments like “garlic sauce” or “rice paper.”

You inhabit another cityscape now: pagodas,

inscrutable black marks on neon signs. Roasted scorpion.

The music of its pretty women tapping their heels

along crowded sidewalks echoes just beyond my hearing.

Can they read in your face what I would read

were I not uncountable miles away?

Mornings I take your bottle of hot sauce, twist off the cap

and shake uncertain drops onto cooked eggs.

Pungent and sour, the scent rises.

I smell what you smell, taste what you taste.

Uncountable miles away you gaze upon a great

wall of stone and bricks, tamped earth and wood.

I stare out the kitchen window.

The neighbor’s rickety fence blocks my view.

One day soon you’ll leave behind the spicy soup,

spend some necessary time over the Pacific.

Your atoms and molecules will reappear before my eyes,

an apparition out of the western sky after

our sun sets into the same Saturday morning

you woke up to when my Friday eyes were closed

in afternoon dreams uncountable miles away.

(Issue 23, Cha)

The persona in “Ghost Husband” imagines a reunion to happen only in “afternoon dreams”—all in all, a more sober, less romanticized contemporary update on the vagaries of long-distance relationships.

Renée M. Schell’s poem, “gender appropriate” this time, describes the separation of a couple in the present. The husband is away in an Asian city, which to the persona’s mind is saturated with “strange tones” and “alien vowels.” We know the husband resides in Asia, as the poem provides these clues: “garlic sauce,” “rice paper,” “pagodas,” “spicy soup.” The time difference—“our sun sets into the same Saturday morning / you woke up to when my Friday eyes were closed”—also indicates that the persona lives in an American time zone, “over the Pacific,” contrasted with the one observed by the husband. “Uncountable miles away,” repeated four times in the poem, emphasizes the immense distance between husband and wife. The distance is so great and so abstract that the wife uses “ghost” to modify her husband, as though he is now on an entirely different plane of existence.8 In Li Bai’s poem, the wife can imagine only very little of the daily realities of her husband’s temporary home—perhaps a suggestion of the restricted experiences of Chinese women at the time, whose lives were often limited to domestic matters. In Schell’s poem, the wife tries to comprehend the foreign land currently hosting her husband—“a land I do not know”—and she is able to make a number of conjectures regarding the differences in language (“strange tones, alien vowels”), food (“Roasted scorpion,” “spicy food”), and cityscape (“pagodas,” “inscrutable black marks on neon signs”).9 Added into Schell’s poem is a pang of jealousy felt by the wife, expressed not so subtly in “The music of its pretty women tapping their heels.” Indeed it is realistic for the waiting wife to wonder if her husband, now “uncountable miles away,” might be attracted to those well-dressed and “pretty” women of the East. Instead of promising to meet her husband, as in Li Bai’s poem and its updates discussed above, the persona in “Ghost Husband” imagines a reunion to happen only in “afternoon dreams”—all in all, a more sober, less romanticized contemporary update on the vagaries of long-distance relationships.

* * *

In his introduction to Derrida’s ideas of deconstruction and photography, the painter Gerhard Richter suggests that translation means that “something is presented, interpreted, explained, and even understood in terms of something else.”10 Seen in this way, the three contemporary poems discussed can be called transgender, transtemporal, and transcultural translations of Li Bai’s poem, read through the prism of Pound’s rendering.

Hong Kong Baptist University

Footnotes

[1] Introduction to Pound’s New Selected Poems and Translations.

[2] Introduction to The New Directions Anthology of Classical Chinese Poetry.

[3] Lucas Klein, Los Angeles Review of Books, July 14, 2016.

[4] Other translations of the poem can be found here.

[5] Jun Tang, “Ezra Pound’s ‘The River Merchant’s Wife’: Representations of a Decontextualized ‘Chineseness,’” 2011.

[6] The influence of Pound’s translation in Noon’s poem is obvious. Noon writes, in a private correspondence, “Haul out your Ezra Pound Selected Poems, turn to Cathay, his translations from the Chinese, and you’ll find a poem called ‘The River Merchant’s Wife: A Letter,’ deriving originally from Li Bai.”

[7] Jun Tang, “Ezra Pound’s ‘The River Merchant’s Wife,’” 2011.

[8] The use of “ghost” here may also be a play on words, as a common Cantonese slang term for Caucasian foreigners is gwai (ghost). Gwai can be used as an adjective, for example, a white man is called gwai lo (ghost man) and a white woman is called gwai por (ghost woman).

[9] Hong Kong, for example, is known for its neon signs.

[10] Gerhard Richter’s introduction is found in Jacques Derrida’s Copy, Archive, Signature: A Conversation on Photography.