Two Poems for Pascha

Bema

In Greek it means step. In church

it separates me from the nave, where the quiet

sit and wait. Behind the screen

the altar boys, age twelve, arrange

a crucifix between them. Each boy

in his golden threads with his own Christ

treads among us, carrying a gallery of icons

too large for a boy to hold. Outside

it’s Easter. We pace around the church three times.

The boys are growing tired. I can approach

one now. I ask him if it’s hard to bear

the solid cross. He says it’s hollow.

May I touch it? No, not today. It’s Holy Day. Maybe

when no one is looking.

It’s midnight now.

We must proclaim that Christ has risen

from the dead. We kiss each other once

on each cheek, side to side, responding that,

Indeed, He has.

It’s rote. I don’t know what it means

yet. They’re sounds. I’m young. They’re old,

old sounds. No one goes back inside.

We’re hungry for celebration: Christ

has risen from the dead. Give us our bread,

and all that. But the present

is inside with the priest, preaching. Stay,

he says, as hoards walk down the marble steps.

Stay and listen to more sermon. I obey. I can see

through the cracks in the screen, the boys are changing

back into their own clothes. I imagine

I could try that robe left hanging

on a hook beside the cross, behind the altar font.

I take a step sideways and enter the circle

of the forbidden room. One move and I know

where secrets are: a marble bowl

of water, bread bloated on a platter,

a palm-size house that burns oil. No one

sees me. The priest keeps speaking.

His voice comes to me

through the crucifix on the wall. I touch

the robe and the blessed Book. I am too small

to understand. The priest goes on.

He knows every word. He

understands. He’s a good man. Saving souls

and all that. No one is there to know it. I pick up

the cross. It’s too big. I call out, God. I’m here.

My words linger like frankincense

in the unholy air.

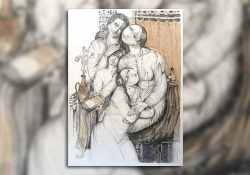

Incomplete Art

My father displayed his new painting with a note:

“I don’t know where I am going with her hands.”

And where should he go with her hands—

now a blur to signify the question of hands.

In the Sistine Chapel, among the angels, we waited

to be named by Adam’s outstretched hand.

Michelangelo painted the birth of man. Eve

took shelter behind God’s mute hand.

A formality of postures, I nod. I understand

the veined map of a body textured by hand.

One touch will hush, decompose the remorse

of where one might go, by the sleight of what hand.

One touch will crosshatch, unheart

hope, and die by the brawn of one hand.

Spoken for in the turpentine temples of love,

I was sculpted and cored by the stroke of a hand.

Eve said nothing, I said. Nothing I say

like law. Absence is an art of the hand.

The artist creates, but I’ve tired of ends.

In worship, wisdom has folded her hands.