Four Poems

Translator’s note: Idea Vilariño (1920–2009) is an essential figure in South American poetry, one of only three women poets featured in Copper Canyon’s 2014 anthology Pinholes of the Night: Essential Poems from Latin America. Vilariño prided herself in her independence; on being a poet, not a poetess; and spent her life as a teacher and professor of literature. She was one of the few women members of the Generation of ’45 group of Uruguayan writers, whose legacy still casts a long shadow over contemporary writers and which included such writers as Mario Benedetti and, as an ex-officio Argentine member, Jorge Luis Borges.

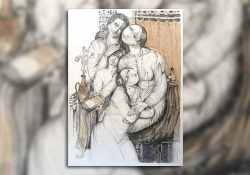

The Cervantes Prize–winning novelist Juan Carlos Onetti was the most senior member of that group. Vilariño and Onetti carried on a love affair that is one of the most famous in South American literature, a match for Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, or, to leave the world of literature, Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart. Vilariño was very beautiful, resembling a young Lauren Bacall. Onetti was eleven years her senior and, in photos at least, ugly as a frog in heavy, thick-lensed glasses. In response to their love, Vilariño wrote her best-known book, Poemas de amor / Love Poems.

Poemas de amor is dedicated to Onetti, and he is the amor (love) referred to in the poems. The first edition, published in 1957, predates Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton but has much in common with their work. It is a short but intense book, full of poems about sexuality and what it means to be a woman, written in a strong, often angry voice. In 1974 Onetti was imprisoned by the Uruguayan military dictatorship for six months, which provoked an international campaign to free him, with famous writers such as Gabriel García Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa writing letters on his behalf. He then went into exile, as did nearly all the members of the Generation of ’45, leaving Idea Vilariño, stripped by the dictatorship of her teaching post, alone and isolated in Montevideo.

Vilariño wrote many other books, but she continued to revise and expand Poems de amor, her own Leaves of Grass, through editions that grew in length through the decades until a final edition in 2006, three years before her death and years after Onetti’s death in exile in Spain, far from Vilariño. In the end, for Vilariño, Poemas de amor came to be more than a book about single and singular love. It stands as a testament to both the necessity and the impossibility of love in this world, especially for a passionate, independent woman determined to speak with her own voice. – Jesse Lee Kercheval

The Whole Spring

The whole spring

with pigeons and stalks and hurricanes

with buckets of warm water

with a voluminous butterfly

fluttering plush

with a garden a forest a grove

populated by humidity and rotting leaves

and fragrances and mists and whiffs of air

and fierce roots and why not

the whole spring was emptied out

breathing sinking

panting in my bed.

You Didn’t Know

My poor love

you believed

that it was so

you didn’t know.

It was richer than that

it was poorer than that

it was life and you

with your eyes closed

you saw your nightmares

and you called that

life.

Song

I would like to die

now

of love

so you could know

how and how much I loved you.

I would like to die

of love

so you can know.

Neither

Now you’re gone. I smell

your place in bed

your heat that still remains

and at the same time bitter

alienated I know

I am still alone and that

it will be only my body

the sweet the possessed

and never you

that will gather up my life.

Translations from the Spanish

By Jesse Lee Kercheval