Transcending Borders: A Graphic Translation Conversation with Andrea Rosenberg

The Spring 2020 issue of World Literature Today explored a variety of works in the increasingly popular genre of graphic nonfiction. Now, as the year comes to a close, use of graphic media in literary storytelling is still on the rise. With the increase in graphic novel/nonfiction sales comes an increase in the number of languages in which these stories are told. As many of these works feature diverse, regionally specific, and historically underrepresented narratives, their translation into other languages has the ability to transcend not only the borders of their internal comic strips but geological and ideological divides as well. The unique characteristics of graphic works, however, demand special consideration from their translators, who must take into account visual, contextual, and space-related constraints. In order to get a behind-the-scenes view of the process, I engaged in a Q&A with translator Andrea Rosenberg, who offers insight into the art of translating in the ever-expanding graphic literature genre and shares her thoughts on the great potential the graphic medium has to offer the literary world.

Brenna O’Hara: How would you describe your role as a literary translator?

Andrea Rosenberg: I love working as a translator because I’ve always enjoyed using language creatively and using foreign languages, but despite early stints in which I fancied myself a writer, I was never driven by my own vision that I wanted to get down on paper. . . . In some ways it is a service role, but there’s a lot of agency in it too: I’m exercising my own creativity, probably being overly reliant on my own favorite words and other crutches, and so on. I really enjoy translating a variety of texts, everything from academic monographs to graphic novels. It keeps me sharper and is more stimulating. I think most translators enjoy learning, since that’s an inherent part of the craft, and the more different kinds of texts I work on, the more I learn.

O’Hara: How do you feel the process of translating graphic works differs from the process of translating purely textual works?

Rosenberg: Translating graphic narrative is a lot of fun for many reasons, not least of which is that they’re such quick projects in comparison to some of the 450-page books I’ve done. I don’t at all mean that to sound dismissive, as if they’re somehow insubstantial. The magic of it is that you don’t have time to get sick of the book, which usually does happen for me with long texts. That never happens with graphic narratives. They take weeks to translate rather than months, which means they remain fresh and exciting throughout.

And of course the material itself is quite different. Usually there’s not a lot of narration, so the emphasis is on crystalline bits of dialogue. The puzzle has to do not with wrangling endless sentences into submission in English, but instead with trying to get all the nuances of a small number of Spanish or Portuguese words into just a few English words. And I really enjoy the challenge of reading the images—as a word-oriented person, I have to remind myself to do it sometimes instead of relying on the words.

I once started translating a graphic novel when I’d just been sent the script without the images (which weren’t ready yet), hoping that my translation would be close enough that my effort wouldn’t be useless. It was fascinating to discover when the pages finally arrived how many things I had interpreted completely wrong because I hadn’t had the images to work with. I have been reading graphic narratives since high school, when I first discovered Maus, but I’m a dilettante, not a habitual reader of them, so deciphering story from image is a skill I think I’m still developing.

Graphic nonfiction in particular is thrilling because it’s a way of putting knowledge into this really digestible form. It humanizes stories that might otherwise seem too big or abstract.

Graphic nonfiction in particular is thrilling because it’s a way of putting knowledge into this really digestible form. It humanizes stories that might otherwise seem too big or abstract—or too small-ball and irrelevant. Marcelo D’Salete’s Run for It! and Angola Janga help bring Brazilian slavery to light/life for an American audience that is largely ignorant of it, and Paco Roca’s The Winter of the Cartoonist takes the tale of five exploited, overextended artists and invests the reader in their ultimately failed fight to be able to create on their own terms. Roca’s story would probably be just a mildly interesting paragraph or two in most accounts, but in focusing on the characters and their interactions, the story expands and is reinvigorated.

O’Hara: What considerations must be taken into account for graphic translations?

Rosenberg: I’d say the biggest issue is space: letterers are generally working with the same speech bubbles that appear in the original, so you need to make sure that your translation fits in them. This can get complicated sometimes, and I’ve definitely had to drop bits of a phrase to be able to fit the most important ideas in. People often claim that English is more economical than Spanish, but that’s only sometimes true. For example, the verb form in Spanish often reveals the subject without the need for explicitly naming that subject. In English that can mean having to add a word (even if it’s just a little one like “she”). In a tiny space like a speech bubble, that can be significant.

The space constraints also mean that if there are cultural elements in a text that are likely to be unfamiliar to an English-speaking audience, it can be hard to fit in an explanation. In a prose text, I feel no qualms about inserting what’s known as a gloss, a bit of verbiage that clarifies the cultural element. That can simply mean adding something like “the village of” or “the city of” before a place-name if the reader needs to know how big the place is, or it can involve more substantial interventions. In any case, that’s hard to do in a graphic narrative because you can’t just expand a sentence indefinitely. You might have to find a workaround instead.

In addition, because so much of a graphic narrative is human (or humanesque!) speech, I put a premium on naturalness of language. In literature it’s more possible to get away with a stilted tone, but in a graphic narrative, I think, the dialogue has to be utterly convincing. Combining that with the space constraints can make it quite complicated . . .

O’Hara: Have you ever had to sacrifice elements of the translation to preserve elements of the illustration?

Rosenberg: This is definitely another big issue, making sure your translation responds to the illustrations. I do feel lucky that especially Spanish and to a lesser extent Portuguese are fairly close to English in a lot of ways, and we use a lot of the same metaphors and ways of describing things. So in The Winter of the Cartoonist I didn’t have to work very hard to preserve the joke about reading the future in one’s coffee grounds and discovering that it looks black. It works in English too. If it hadn’t, though, I would have had to rack my brains to come up with another joke about a coffee cup to match the illustration, whereas in a literary translation you can usually swap out a joke for a completely different one without anyone noticing. I can’t think of an instance where things haven’t worked out so far, but I’m sure it will happen, much to my dismay.

O’Hara: How closely do you collaborate with the author and/or illustrator in graphic translation endeavors?

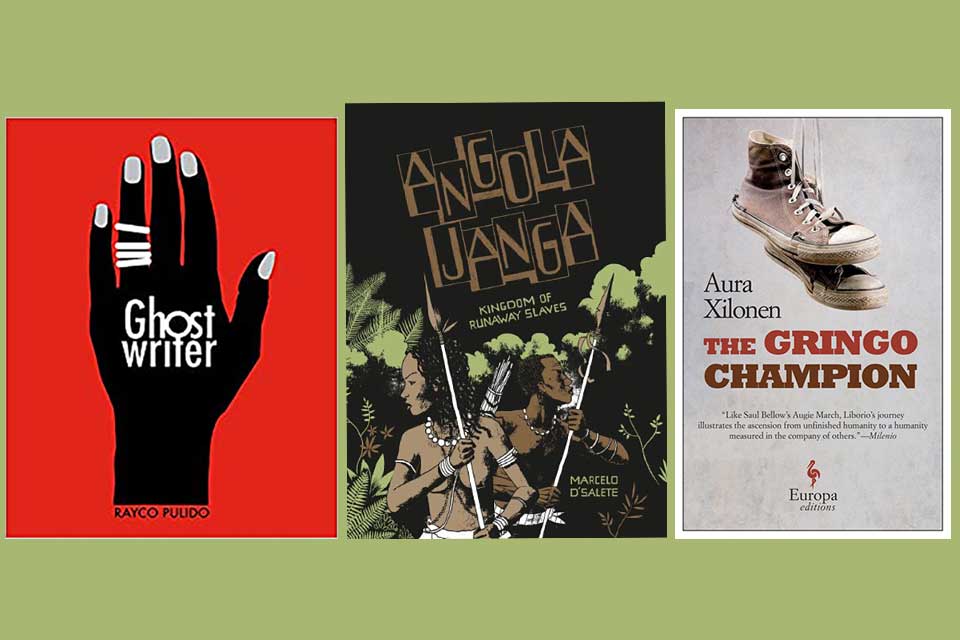

Rosenberg: So far I haven’t worked with authors very extensively. I consulted with D’Salete on some factual issues for Angola Janga when working on the appendixes, and I also had some questions for Rayco Pulido when I was translating Ghostwriter. But I haven’t done any close collaboration so far. Maybe that will turn out to be necessary on that distant day when I find I can’t make my text work with the illustrations.

O’Hara: What is a translating challenge you’ve encountered?

Rosenberg: My most challenging book to date was a Mexican novel that involved a lot of invented language: Aura Xilonen’s The Gringo Champion. Trying to develop a persuasive argot was very difficult, and I found myself pilfering words from the most random places, from the name of a bar in Denver to a term my freshman RA in college used to use.

O’Hara: In your opinion, what does the graphic medium have to offer nonfiction works?

Rosenberg: The accessibility and vitality of the graphic narrative make it a spectacular vehicle for storytelling that has traditionally been dry. I think about all the history classes I took where I couldn’t really feel the connections between events, how one might have caused anger and thus retaliation, or anguish and thus some other response, for example, and so history seems like this scatterplot of almost random, or only mechanically linked, occurrences.

A friend once told me about a Portuguese king who was infamous for his love of roast chicken, which he stored in his pockets and would pull out at random moments during audiences at court. Those details remind us that all those musty figures were human too, with not just the massive flaws (and, sure, occasionally incredible virtues) we’re accustomed to thinking about but also the weird human foibles we all have. And while you don’t need the graphic medium for those details (I was told that story verbally while wandering around the ruins of a Portuguese castle), can’t you just picture the frames of that king on his throne pulling a drumstick out of his pocket?

The accessibility and vitality of the graphic narrative make it a spectacular vehicle for storytelling that has traditionally been dry.

O’Hara: Do you have any advice for aspiring literary translators?

Rosenberg: Networking seems like the most key skill you need for literary translation, professionally speaking, until you get a bit of a foothold. I’m a terrible networker, but I was lucky to meet some good people along the way. In terms of craft, I can only recommend reading everything and translating everything, getting practice at evaluating texts for how well your voice fits them and how worth translating they are. I find that my yardstick’s a bit off in Spanish and Portuguese; I’m more tolerant of texts I might not even bother with in English. So it’s been essential to learn to be more discerning.

O’Hara: Do you have any reading recommendations for graphic works or works recently translated into English?

Rosenberg: I am sad to say that in 2020 I have read almost nothing but the news. A sad state of affairs all around. May that change soon!

December 2020

Andrea Rosenberg is an award-winning translator who currently resides in Carrboro, North Carolina. Her translations from Spanish and Portuguese have won two Eisner Awards and include novels and graphic narratives by Manuel Vilas, Tomás González, Inês Pedrosa, Aura Xilonen, Paco Roca, Marcelo D’Salete, Juan Gómez Bárcena, and David Jiménez. She holds an MFA in literary translation and an MA in Spanish from the University of Iowa, and she has been the recipient of awards and grants from the Fulbright Program, the American Literary Translators Association, and the Banff International Literary Translation Centre.

Andrea Rosenberg is an award-winning translator who currently resides in Carrboro, North Carolina. Her translations from Spanish and Portuguese have won two Eisner Awards and include novels and graphic narratives by Manuel Vilas, Tomás González, Inês Pedrosa, Aura Xilonen, Paco Roca, Marcelo D’Salete, Juan Gómez Bárcena, and David Jiménez. She holds an MFA in literary translation and an MA in Spanish from the University of Iowa, and she has been the recipient of awards and grants from the Fulbright Program, the American Literary Translators Association, and the Banff International Literary Translation Centre.