Queer-Feminist Writing from 1970s Turkey: A Conversation with Maureen Freely on Sevgi Soysal

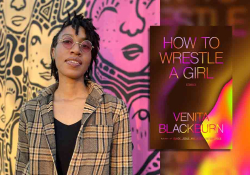

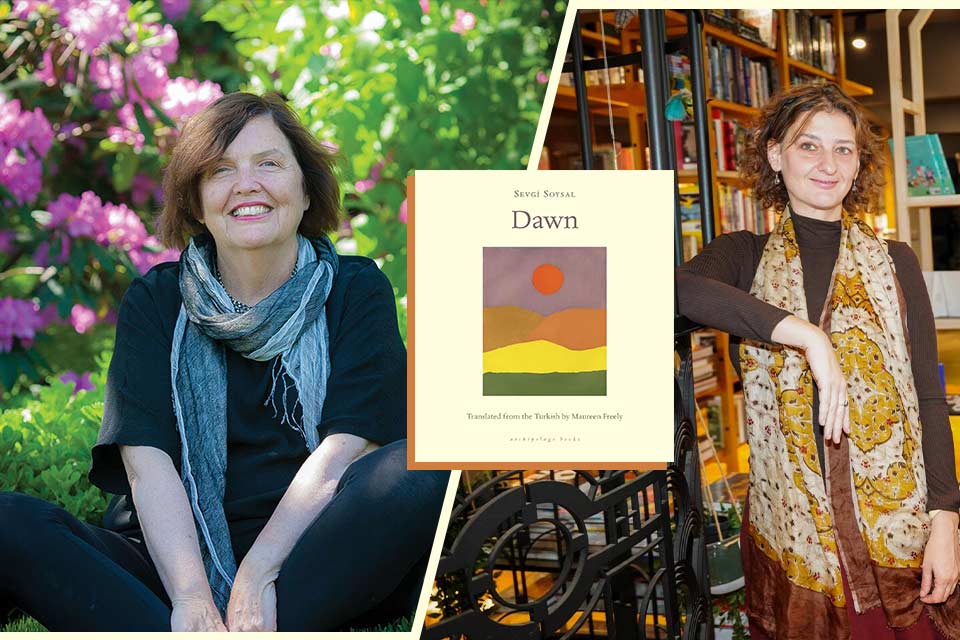

Maureen Freely is an author, translator, and professor of English and comparative literary studies at the University of Warwick. Among her many translations is Dawn, by Sevgi Soysal, which transpires over one night spent in prison. A novel from the 1970s, Archipelago published the first English version, in Freely’s translation, in 2022.

In this virtual conversation as part of the Turkish Literature in Translation Reading Group, Freely shares her ideas about contemporary Turkish politics and literature along with the translation challenges she faced when rendering Dawn into English. Sevgi Soysal’s daughter, Funda Soysal, joins the conversation from Istanbul.

Ipek Sahinler: I know that you’ve read Soysal’s Dawn multiple times over the decades and that each reading spoke to you differently. As its translator, how do you read this novel now, from the present moment, especially considering the very dark time Turkey is going through after the February 6 earthquake?

Maureen Freely: I was reading it, or parts of it, in preparation for our conversation today, and it brought me back to the despair you can’t help feeling at the composite portrait she paints of Adana at that time. She goes into so many different heads, and there she makes visible the system in which everybody is caught. Periodically, she returns to memories of the two prisons where she’d recently spent time, as well as her experiences in Adana as a kimsesiz (solitary) woman in Adana under police protection. That takes me right back to that despair. This is such a beautiful book, and the beauty comes out of the despair and depth of her understanding of the human beings who are caught in this horrible conflict.

One of the passages that really struck me this time was the passage in the very beginning where she’s talking about Oya, who is “afraid of the ugly.” Oya doesn’t know how to deal with it. She almost has a bourgeois idea of beauty. Toward the end of a horrible night at the police station, here’s an extraordinary conversation that Mustafa has with the Kurdish accountant who is obviously going to go down for quite some time, and he’s talking about “beauty” as well. And it’s a very, very different kind of beauty. It’s the beauty of truth and the beauty of pledging yourself to that truth. He’s also one of the most compassionate, loving people in the book. Because of his greater understanding, he has anger in him as well. The next day, he leaves with his head held high, knowing that he’s going inside for a long time. Lots of love, lots of anger. Carrying on from that, Oya realizes, as she leaves the police station, that she’s never going to be free unless everybody’s free.

If you don’t mind, I’d like to share the lines that pierced my heart again and brought me close to tears. It’s just at the very end. It’s so interesting that there are two repetitions of names. There’s Abdullah, given to three different bad guys at three different points in the novel, and then there are two Cevdets. The first is the child in prison with his mother. There’s also another Cevdet—the little boy Oya meets at the end. The passage goes: “Unless they can all live together in freedom, she will remain with them behind bars. If she doesn’t, she’ll only have tricked herself into believing that this eye is really winking and that she’s truly free until she’s locked up again by all the other Cevdets under the sun” (Dawn).

I think that’s what Sevgi Soysal must have learned through writing the book, because not very much has changed in the way that the system—which we would like to be resisting—operates. I mean, that’s the other thing I was very much feeling as I was translating it two years ago during the pandemic.

Sahinler: Can you talk a little bit about how you translated this loaded passage that contains complex grammar and compound sentences?

Freely: I had my baptism of fire with Orhan (Pamuk) in terms of long sentences! My humble aim, when I’m translating a great writer doing something extraordinary, is to try to figure out beneath the meaning of the words and to understand the strategies they’re using to bring together this artistic effect. When I say “artistic effect,” it almost sounds cold. What I actually mean is “the music of the soul.” Regarding Soysal, it is about how she takes me to the point where I’m feeling and thinking something at the same time, and where I’m also going into the depths of something altogether. Because I am a novelist myself, I’m involved in that kind of thinking as well. So, I just try to imagine what’s going on and then try to create a voice and find her voice. To me, novelists are very annoying. We talk about “voice” in a mystical way without analysis. I do try to analyze it, but I can only analyze it afterward—to look at what I’ve done wrong or what seems to be working.

My humble aim, when I’m translating a great writer doing something extraordinary, is to try to figure out beneath the meaning of the words and to understand the strategies they’re using to bring together this artistic effect.

Going back to Soysal, she switches tense and focus so often. If you look at the first page of Dawn, she builds this extraordinary image, which is also a metaphor. She’s describing all of Adana and its rich and poor. A police car then cuts in and things get very, very ugly. So, it was not just about translating that particular passage but about how to register those smoothly done but actually quite abrupt sentences, with intense switches in focus. This is one of the things that my publisher (Archipelago) was very understanding of, and we had a good conversation about it, because I didn't want to alter those shifts between present tense and past tense. They seemed to me to be a bit easier to do in Turkish than in English anyway, but they were there for a reason. I think that Sevgi pushes at that convention a little bit harder so that there are these abrupt shifts, and as the translator, I wanted to keep those.

Sahinler: You mentioned that you’re interested in the way the book charts this strengthening of political purpose, even as it explores the inner lives of characters on all sides of society and the state, often taking them to a breaking point. How do you think the novel explores political commitment, political doubt, and genuine political action?

Freely: First of all, Dawn is a really unusual book, for it goes into the hearts and minds of the so-called “enemy” or perpetrators. It also shows how they are caught in systems of thinking as well as hierarchies where they’re all afraid and all punished. Thus, even Muzaffer Bey, the ex-colonel who’s now in charge of Mediterranean industries, can be crushed by Turgut Bey, who is mentioned as a refined man who went to Robert College. I like that touch (chuckles)! But he can still just push down on the police chief because this guy can’t end a strike, underlining the idea that even a colonel can’t end a strike. So, I don’t think many of us, especially those of us who have been involved in any kind of political activism, have the imaginative generosity to go into the minds of the people “on the other side.”

Dawn is a really unusual book, for it goes into the hearts and minds of the so-called “enemy” or perpetrators.

The other thing that I so admired when I was translating it is that in Dawn, Soysal achieves, in a very limited space in twelve hours, really everything that Orhan Pamuk’s Snow tries to do. From dusk till dawn. Because every element of the puzzle is there: you have the Sunnis, the Alevis, and the Kurds, you have the Gray Wolves, you have the workers, you have the factory owners, you have the police chief, you have the Roma, you have the political prisoners. Even more notably, you have the prisoners from the general prison who represent all different types of tragedy. They’re all there. You must hold all that heartbreak together.

The other thing Soysal might be saying here is that one cannot carry on resisting and hoping for a better future unless they’re honest about the whole picture and their own part in it. Therefore, it won’t surprise you to hear that one of my favorite characters is Mustafa. Because he’s not very articulate, yet he is soul-searching and asking very big questions about himself silently while this is all going on. Also, he’s so much better at dealing with the police chief than anybody else because he’s been interrogated by the hard-core Istanbul interrogators, and this Adana police chief doesn't know what he’s doing.

Anyway, what did you think about this, Ipek? How do you understand resistance carrying on the hope through Dawn?

Sahinler: When I think about hope and resistance in Soysal, what always comes to my mind is this Turkish expression isyankar neşe, which literally translates as “rebellious joy.” But to me, a more accurate translation of this, thinking of Soysal, would be “queer joy.” This is mainly because she is a unique author who goes beyond feminism—though she has so far been referred to as a “Turkish feminist writer” and has been studied through feminist lenses. I’m saying “queer joy” because I read her as a queering writer who dares to question (hetero)normativity in 1960s Turkey, as well as idealized forms of masculinity, femininity, family, etc. She skillfully plays with these intertwining constructs, and how she manages to do this is by way of “queer joy” and laughter.

Freely: Definitely. She goes beyond everything, even beyond ideology.

Sahinler: Having said laughter, how was your experience in terms of translating Soysal’s idiosyncratic sense of humor?

Freely: This makes me think of Hannah Arendt on laughter, but I won’t go there right now. . . . Let me share some strategies I used to translate Dawn. I’d start with a part of the novel where I was unable to bring across the full humor. For instance, the sections about the Ankara Central Prison. In this part, the characters speak in very particular ways, which come across so powerfully in the Turkish version. It was challenging to translate those parts, and especially people who don’t have education. While it’s very easy to belittle them, it’s almost impossible not to locate them as a different disadvantaged group in a different place, and that just sounds horrible. So, I drew a line.

The rest of the humor is situational. You really need to understand the Turkish context. But if you can keep the music of the voice going, then some of these things can happen by themselves. So, when I speak to poets about untranslatable things, they’ll just say that whenever they come across something that is a concept, or a word used in a specific place but nowhere else, they’ll go to the other attributes of the word like how it sounds, how it passes across. So, sometimes you can do that. One of the things that made me laugh as I was reading the book this week was Hüseyin and Mustafa. They’re in the police cell, and Mustafa is getting more and more angry at his brother and particularly angry at his maxi coat! You can see that that’s something you can carry over, and then there’s an exchange, you know. Hüseyin is worried about his future as a lawyer in Adana, and he goes, “What do they say about me?” and Mustafa responds, “They say nothing about you.” Then he just says, “Can you give me a cigarette?” and Mustafa says, “It’s too smoky in here already.”

So, the laughter, or my laughter, is from what they’re saying to each other. This goes back to the expression you just used, isyankar neşe. Here, “rebellion” also means refusing to stand on the line that you’re supposed to stand on, which is what the whole book is about: refusing. We all know that there was certainly a strong rule in those days. You know, the personal had to stay out. But Soysal refused that and said, “No, I’m going to speak. I’m going to talk about the women who are involved in this story.” We see this attitude in Dawn. Think about Ali's house in the gecekondus (slums). They don’t know what to do with her because they cannot even classify her as a woman. You would think that, if she were a conventional writer, she would want us to be sympathizing with her and find some solidarity. But there isn’t any! It’s just because of how people are seeing each other.

Another funny part is where Ekrem comes in, the horrible neighbor—he’s not Alevi, not anything—doing some silly business with Germany and is full of himself, and that conversation is completely wonderful because Mustafa is just insulting him. So that’s an example where a lot of politics comes in mainly because of the naming of parties. I took the view that people are just going to have to live with it, they can get the gist. But these are just different parties; in terms of the novel, the insults are what matter.

Sahinler: What you just said is very meaningful to me because it reminded me of how Soysal’s “strategy of refusal” works on a lexical level. She frequently uses verbs such as bırakmak (to leave/release), gitmek (to go/leave), yürümek (to walk)—which are all consanguine. I particularly think of Tante Rosa, her 1968 novel, where the female heroine perpetually “refuses” and “leaves” things, individuals, and institutions that are anchored around predetermined names or identitarian categories. Whenever Rosa becomes a part of “this or that circle” (şu ya da bu çemberin bir parçası haline gelmek), she leaves. I believe this was the expression she used in the book.

Freely: Yes, we also see this in Soysal’s life. She was doing feminist programs in TRT (Turkish Radio Television Corporation) before there was feminism. She was always looking at things differently, but in a very spirited way. As I said, she had “true laughter”—one that shook the foundations of her own belief system. As we know, the best humor comes from shaking the cage in which you are. Also, there was feminism at that time, but second-wave feminism comes later. So, she was thinking about these things before people were thinking about them collectively. She was living by her own ideas.

The best humor comes from shaking the cage in which you are.

Sahinler: Dawn is often referred to as a “March 12th novel” (12 Mart romanı). Simply put, it is literature that tackles the psyche of the 1971 military coup and its aftermath in Turkey, often written in the service of a socialist cause. How do you think Dawn stands within the genre of March 12th novels?

Freely: I think it stands alone. The category of March 12th literature is not invented by any of the authors who are inside it. Dawn, alongside Soysal’s Yıldırım Bölge Kadınlar Koğuşu (Yildirim Bölge Women’s Ward)—which I also translated yet never got published—were my education into what was going on and what wasn’t in the papers and being told to the likes of me. But what is absent here—and you can probably give me other examples of people who are like Sevgi—is that sense about what we’re going to be, which is always a problem and still is a problem: “because our enemies are so bad, we’re not going to talk about ourselves. We’re not going to look about. And if we do, it’s going to be in the privacy of the Istanbul prison or in Ankara prison.” I think she goes way, way beyond that, and I think that’s one of the main reasons why Dawn has gone on to retain such importance. I can’t tell you how pleased I am by that, because when I first read it, I had no idea that it was going to carry on its long life. Some kinds of beauty last . . .

Sahinler: What were some of the translation issues, problems, or paradoxes that you had while translating Dawn? Can you share some examples?

Freely: Oh, they’re in the Ankara Central Prison passages! They were just any number of words. I had to go to people to ask for help, and then most of them were like, “Oh, I don’t know.” There were wonderful local words. As is often the case, the first page presents challenges, and I had to go back and back. Because first, it’s a really powerful first page, and second, it’s very difficult to get it to work in English. So, it wasn’t one word but every single word and sequences of it. It is because Turkish is so much more flexible. It is because Turkish is not positional, and you must put words in a certain order or otherwise they lose their meaning.

And one of the things I learned about Sevgi is that she writes quite directly until there’s a reason not to, and at the beginning, when setting the stage, there’s every reason not to. So, the passive voice comes in, and she is a great artist of passive voice. She uses it very selectively for a particular set of reasons, and there was that going on in the first paragraph, but not as much as the first paragraph of Yıldırım Bölge Kadınlar Koğuşu. The English reader would be like, “Who said it? Who did it? Where is it?” (chuckles). Because there is a play on a saying, and then all these handles of hatchets are getting “burned,” and everybody was “burned up” because English doesn’t have all the connotations of “burnt” in the same way. It was such a beautiful beginning in Turkish, and I almost gave up . . . (chuckles)

So, as I’ve said before, the first page of Dawn—and the first page of its last section, which is when the false dawn is happening—gives you the sense of having worked on something for a long time, then returning to it, that the longer you do that, the more you appreciate the art that’s gone into it. Because if it’s working, it just reads funny. But no, that’s not how it was made . . .

Sahinler: There is a line in Orhan Pamuk’s Nights of Plague: “you couldn’t really solve a problem in the Ottoman Empire without throwing someone into prison.” Do you think this is the case for the Republican period as well?

Freely: Yes. Prison is always there. I just finished translating another book by Suat Derviş called Prisoner of Ankara. It’s not just prison, but what happens when you get out and what doesn’t happen when you get out. I’ve never been in a prison or Turkish prison, and hope that this continues, but prison plays a central part in the history of Turkish writers and dissenters. So, yes—it’s there. I’m sure you also know many people who have been or still are in prison, who all carry so many silent wounds. I think we see prison in these books because it’s in the society and people’s lives. One of the few places you can tell the truth about this human experience is in fiction and poetry.

I think we see prison in these books because it’s in the society and people’s lives. One of the few places you can tell the truth about this human experience is in fiction and poetry.

Sahinler: About the difficulty of translating humor . . . was it more to do with the use of colloquial language?

Freely: A lot of the difficulty had to do with the colloquiality of the humor. Each character was speaking a very different kind of Turkish. You couldn’t even say “Anatolian rural Turkish” because that would be different in different parts of the country. One of the characters, for instance, was a state-registered prostitute. Another one was a Kurdish “drug mule,” pretty much run by her husband. Another one was someone who has worked in Germany whose rural accent was Germanified. When she attacks our heroine, she asks for a “kuss”; alongside these, they’re writing folk songs and playing very daring sex games.

So, it’s not just what they say but about how they are creating their own rebellious society without ever having the concepts to understand where they are. Again, my job as a translator is not to find the right word, necessarily, but to try to convey what I’m sensing about how the writer moves through space. That’s also what I do as a novelist. So, I probably use the same strategies without even being conscious of it. Let me give you an example. There is a particular word that she uses for her “squeeze.” It is kırık in Turkish. I think I finally translated it as “fella.” Before I had tried something else, and it was rejected. I guess I could have gone to you, Ipek. How would you translate kırık?

Sahinler: That’s a hard one. I’d say “broken,” but it also has a deep sexual connotation. Funda, what do you think?

Funda Soysal: In Turkish, we call “fault lines” kırık too.

Freely: Yes, but in this case, she is referring to her lover. It’s a great word. . . . The women in the prison are incredibly inventive with language. But I don’t think Oya knows what kırık is either. So, I’ll just continue to be mystified by that! While “fella” was not the right word, none of the other solutions were perfect either. If you can’t do one thing, you’ve got to do the rest of it much better. It’s a question of balance because that’s the main thing, to make sure she jumps off the page because she’s wild. You know, wildly joyous, and isyankâr (rebellious).

Sahinler: “Wildly joyous” is a beautiful way of putting it.

Freely: I have a question for Funda. Could you explain for people all of the work that you've done to bring this work back into homes?

Soysal: I don’t know about bringing it back. I think when an author dies as young as she did, at forty, a time of grace must pass until the sadness of the initial loss subsides for those left behind. When I was twenty-five, my aunt Mine Kazmaoğlu encouraged me to take over her literary legacy and İletişim publishing wanted to republish her entire oeuvre as a classic. Bülent Erkmen made the book covers with my mother’s portrait, as my aunt and us agreed that having her gaze over us was ever a good thing. Fifty thousand copies of Tante Rosa were printed since then in Turkey and she found an entirely new audience, who loved her for her works, just like I did. My father, Mümtaz Soysal (1929–2019), had kept every piece of paper left from her, and I discovered them in due time and shared them, only to discover that there were many people who were as curious about her as me, and together with İpek Şahbenderoğlu, we published three entirely new books. There are still her prison notebooks and letters with my father, some of which I already published, but first, the transcripts of her trials will be published, this fall. But what I want to say is thank you, Maureen, I am sure my mother is very happy to see Dawn, which she was very proud of, getting such renewed acclaim as it did with your translation to English.

She had herself also started with translations, and I liked looking into what she chose to translate and how that may have influenced her writing. She had translated stories by the German author Wolfgang Borchert, who also died very young and wrote about incarceration under the Nazi regime, so I always thought that this may have given her an edge to write about what happened in Turkey in the 1970s. She loved the Turkish language and used it so well and evocatively, perhaps like Rainer Maria Rilke, whom she also translated.

Freely: Yes, it is also crucial to note that she belongs to more than one language. And translation is a very good way of learning about your own language, its possibilities and beauties. Do you know who first gave me your mother’s books?

Translation is a very good way of learning about your own language, its possibilities and beauties.

Soysal: I heard you said this. My father, huh?

Freely: Yes, your father. I was working as a very bad secretary at Amnesty International. He was on the board as the international executive at that point. In those days Amnesty was an egalitarian place. So even if you were a really bad secretary, you got to meet people! And he was very kind.

Soysal: That must be after my mother passed away.

Freely: Yes, it was in 1977, just after she passed away. He had just lost Sevgi and gave me Yıldırım Bölge Kadınlar Koğuşu. But he also said, “Şafak is my favorite; that’s the one I love the most.”

Soysal: Really? This is interesting, because I recently heard him on tape and he talks about how he had read her very first book, Passionate Bangs (Tutkulu Perçem), and was very impressed with her back then. In any case, he left it in very good hands!

Freely: Yeah, that’s the story. . . . But I was very little when those two books changed my life. I still have Yıldırım Bölge Kadınlar Koğuşu in a box here. You know, it was before the internet thing, so maybe we can find a secure place for it one day.

Soysal: I also want to add a small thing on “beauty.” She has this one line in Dawn, where she says “güzellik gölgesizdir, sığınamazsın” (beauty is without a shadow, you cannot hide under it). I had thought a lot about that line before, trying to understand what she meant with it. I then read you translating it as “What use will beautiful sentences do me in here. Beauty knows no shadows. It has no place in here.” It is a different meaning than the one I had thought, so translation also gives meanings that one had not thought before . . .

Freely: Wow . . . I need to think about it. Gölgesiz (shadowless) is a word for me that works better in Turkish than in English.

Sahinler: With the notion of “beauty” (güzellik), there comes “ugliness” (çirkinlik). We just said how Oya was “afraid of the ugly.” What do you think about the interplay between beauty and ugliness in Soysal, Maureen?

Freely: For me, the most precious kind of beauty is the beauty that’s hard-won. Maybe it’s gölgesiz, because it’s the one that you don’t see until you have walked through all the shadows. But I’m still mystified by the “beauty that doesn’t have a shadow” and that you can’t hide underneath it. I have to think more about this notion. . . . Other than that, in Dawn, there is the idea that nobody is free until everybody is free. I’ve recently come across this idea in Suat Derviş, who I’m currently translating. There’s a female character who speaks like a derviş, a deity, talking in paradoxes. There’s this “other ethos” that comes through in so many of these novels that is never quite named. As you know, one of Hasan Ali Toptaş’s books is called Gölgesizler.

Sahinler: You’ve contributed tremendously to translating Turkish women writers into English and helped them be accessible worldwide. I want to thank you for that as a reader. How is your second Suat Derviş translation going?

Freely: It’s a very interesting one. It’s another melodrama, but it has different translation challenges, because she’s not the same kind of wordsmith. And thank you for saying that. I get a lot of offers because of my accidental privileged status after Orhan. But I only accept very few. . . . I just had the luckiest pandemic because all I did was translate Sevgi Soysal, Tezer Özlü, and Suat Derviş. They were the ones who helped me survive the pandemic when I was all alone in this house for eighteen months. And I also consider it my duty to suggest other Turkish titles. But I don’t want to hog all the wonderful books to myself, so we should be a community of translators. I think I’ve said it before to you, Ipek, but please suggest titles if you can think of any. Because without our work, these important voices will continue being lost. So, I’m depending on you guys.

I just had the luckiest pandemic because all I did was translate Sevgi Soysal, Tezer Özlü, and Suat Derviş. They were the ones who helped me survive the pandemic when I was all alone in this house for eighteen months.

Sahinler: Can you unpack what you’ve just said about your “privileged status” related to having translated Orhan Pamuk? How do you feel about that?

Freely: You know, I was on the receiving end of a lot of “Orhan hostility,” so when I first started translating him, I kept saying: “Look, he’s opening the door. He’s not necessarily interested in anybody who follows on after him, but that doesn’t mean the door isn’t open.” So that’s how it happens. . . . When I was starting out, people would come to me and say: “We knew one Turkish author name, and now we know two with Elif Shafak. But is there such a thing as Turkish literature?” They don’t ask that kind of thing anymore because things have changed. Culture changes slowly, and as you know, translation is not a big money-making venture. One of the reasons I went into it is because I wanted the books to be in the libraries, to be in the classroom.

Sahinler: Thank you for our conversation, Maureen and Funda.

Freely: Thank you for doing this. We’ve come a long way, so let us carry on doing so.

February 2023

Editorial note: You can read a 2017 conversation with Maureen Freely, conducted by WLT’s managing and culture editor, Michelle Johnson. See also her “A Translator’s Tale” essay in the November 2006 issue devoted to Orhan Pamuk, plus “The Prison Imaginary in Turkish Literature” in WLT’s November 2009 issue.

Born in Ankara in 1975, Funda Soysal graduated from Robert College in Istanbul in 1992 and received her BA degree in history from Grinnell College, Iowa, in 1996. She received her MA in modern Turkish history from the Atatürk Institute at Boğaziçi University, and she began a PhD in history, with a dissertation on the 1895 financial crisis. Since 2003, she has been representing her mother’s literary heritage with İletişim Publishing in Turkey and with AnatoliaLit Agency internationally.