Poetry with “Something at Stake”: Benjamin Myers on Past and Present

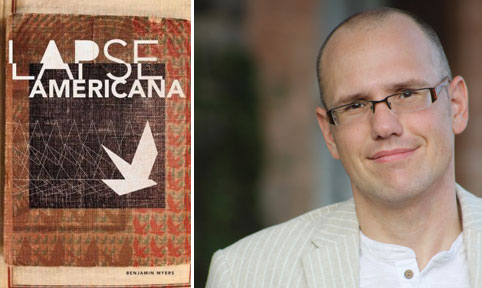

April means tax stresses and spring, whether for you spring involves heavy snowfall or seasonal allergies. But in the U.S. April is also national poetry month. For Oklahoma poet Benjamin Myers, poetry can inhabit the past and present simultaneously; it can rescue and engage; it can even teach you to be yourself. Myers’s second book of poetry, Lapse Americana, was released last month, and it works by way of contrast, placing its feet both in the Pax Americana and in the “lapses” of the new century. If you agree with Myers that fine poetry is “well-felt”—if fine poetry is verse in which, “regardless of the facts, the emotions ring true”—you’ll appreciate his reflections below on his new work, on memory, and, among other things, on contemporary history.

Sara Wilson: What issues or questions from your first collection, Elegy for Trains, do you continue to comment on in Lapse Americana?

Benjamin Myers: Both books are very much about memory, though Lapse Americana approaches the theme more by means of contrast: remembering and forgetting. While I admire poets like Frank O’Hara who can be totally in the moment, my poems are often an attempt to inhabit the past and the present simultaneously. They are also, inevitably, demonstrations of the limitations of that attempt. Those limitations, I hope, give the poems their poignancy.

SW: Fathers are prominent in both collections. In Lapse, some poems are narrated by fathers; some are about famed fathers in literature, as in “Anchises.” Why fathers?

BM: My first book was really an elegy for my father, and this second book is dedicated to him (mainly because he was such a fan of the New York Quarterly and would be delighted that it is publishing my book). He was a poet and my first real poetry teacher. I’m a father now myself and often find myself wondering what he would say or do as I raise my own children. So I suppose the father motif in Lapse Americana is another way of getting at that theme of time past and time present.

Beyond that, I often write about being a father because, quite frankly, it is the toughest and most rewarding job I have ever had, and I feel a need to document that in my poems.

SW: You engage with a wide variety of poetic forms, including prose poems. How would you define your poetics?

BM: I’m not interested in prescriptions of what poetry should or must do but rather in finding out all the things that poetry can do, the possibilities of poetry. Sometimes I use traditional forms; sometimes I use free verse, which at this point in literary development is really just another formal choice among others, carrying its own range of traditional associations and allusions. My simple working criterion is that the form fit the tone or mood of the poem.

Beyond the question of verse forms, I find myself torn between the process-oriented poetics of much postmodern American poetry and the lapidary approach of Yeats and the high modernists. I try to make that a useful tension.

SW: Your verse contains armadillos, city dumps, grass fires: at times it smacks of the Midwest. How do you dodge the problem of reductionist Midwestern imagery like the dustbowl, Route 66, Tornado Alley, etc.? Perhaps a better question would ask how you work with conventional ways of describing this region of the country.

BM: I think that all good poetry is, in a sense, “local” poetry, because the only way of getting at the universal is through the particular. Philip Levine’s greatest poems are about Detroit in very particular ways, and, even though I have never set foot in Detroit, those poems engage me and move me in powerful ways. I think the trick is to avoid sentimentalizing or romanticizing the “homeland” from which you write, to avoid cliché at all costs. I know “authenticity” is a problematic term for some poets and critics, but I think we all know it when we see it.

SW: People have compared you to Woody Guthrie and Walt Whitman. The number of references to “I” and American voices found in Elegy for Trains as well as Lapse Americana certainly seem to validate the Whitman comparison, and many of your poems feel like ballads, an effect that seems to warrant the comparison to Guthrie. Who are your influences?

BM: Whitman, of course, is an influence on me and just about everybody else, but my more immediate influences tend more to the subdued and subtle. Jane Kenyon is a very important poet for me due to her ability to use very plain language and description to suggest great depths of feeling and mystery. The great poet of the Tang Dynasty, Du Fu, has had a profound influence on me for the same reason: when he writes, “The bamboos rattle in the cold / the sound invades my sleep” (trans. David Young), he has opened up a whole world of weariness, anxiety, and a sense of cosmic indifference through very simple language.

William Stafford has had a big impact on my writing, probably because I came to him at a time I perhaps needed rescue from the tradition of “difficulty” and complexity in poets like Eliot. I still love Eliot, of course, but Stafford, Kenyon, B. H. Fairchild, Andrew Hudgins, and others have taught me how to be myself in my poems.

SW: Death features prominently in Lapse; in various poems it is connected with limitation as well as promise. Can death as it is found in your work be linked to a notion of poetry as a democratic project?

BM: Well, I suppose death is a very democratic institution. Mortality, of course, is the great commonality in the human experience and has thus been central to poetry since Gilgamesh and Homer. I’m only half joking when I tell my students that all poetry is about one of three things: death, sex, or God (or for John Donne, all three at once). Death, and our perception of it, is obviously connected to our perception of time, and it is really time that fascinates me.

SW: What does the title Lapse Americana contain?

BM: It contains lapses in memory, lapses in faith, lapses in courage, maybe lapses in character. But to posit that there has been a lapse into forgetting or doubt presupposes a constant norm of remembering and of faith. So, it’s not as dark a book as the title might suggest. I also meant the title to reflect on contemporary history, the difficulties America faces at this point in our history. I found it interesting to look back at the past from the standpoint of this very changed America. I can never really get far beyond the gravitational pull of the elegy.

SW: In a review you wrote last July, you mention that in your late twenties, you made a vow “to only write ‘real’ poetry, poetry with blood and guts.” Blood and guts are both literally featured in Lapse, but how would you describe your development as a poet since that vow?

BM: I’ve tried to stick with that vow, not in the sense of writing “raw” or angry poetry but in the sense of writing poems in which there is something at stake, emotionally. Purely intellectual poems may be interesting for a moment, but it is the poetry that touches us that we come back to again and again. Of every poem I write, I ask myself if it is three things: vivid, engaging, and poignant. I may hit those goals to varying degrees in various poems, but those are my standards, because that is the kind of poem that sticks with me as a reader.

Benjamin Myers’s latest book is Lapse Americana (New York Quarterly Books, 2013). He won the Oklahoma Book Award for Poetry for his first book, Elegy for Trains (Village Books Press 2010). His poems may be read in many fine journals, including Poetry Northwest, 32 Poems, Tar River Poetry, Nimrod, Devil’s Lake, the New York Quarterly, and many more. He frequently reviews poetry and books on poetics for WLT. With a Ph.D. from Washington University in St. Louis, Myers teaches at Oklahoma Baptist University, where he is the Crouch-Mathis Associate Professor of Literature.