Poet, Translator, Mirror: A Conversation with Miho Kinnas

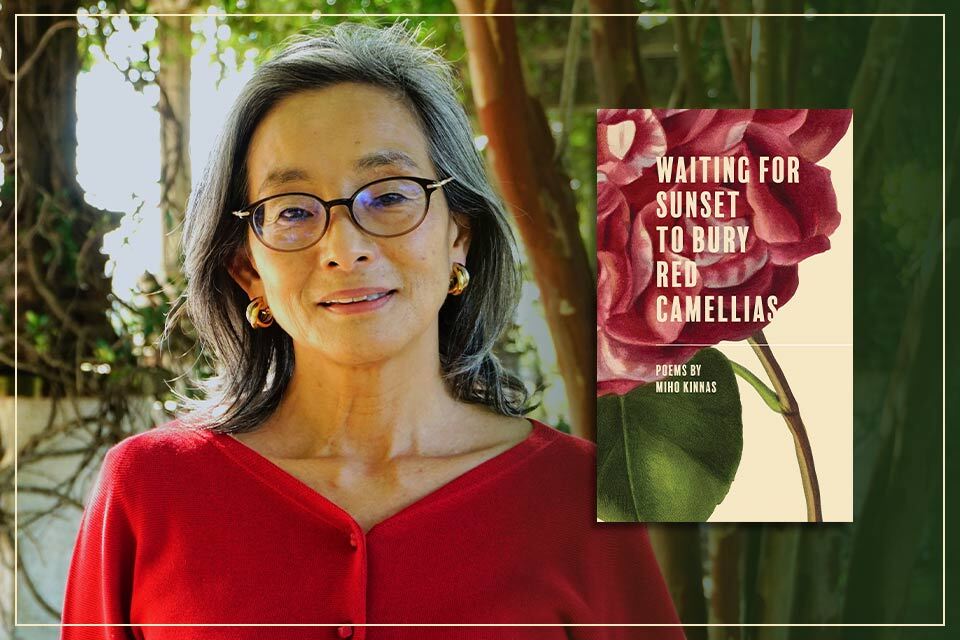

Two-time Pushcart Prize nominee Miho Kinnas recently published Waiting for Sunset to Bury Red Camellias, her third book of poetry. Her two other collections, Today, Fish Only (2015) and Move Over, Bird (2019), were both published by Math Paper Press, which is based in Singapore. Her poem “Three Shrimp Boats on the Horizon” was selected for Best American Poetry 2023. We Eclipse into the Other Side (Pinyon), which she and E. Ethelbert Miller wrote collaboratively, also came out this year as a limited-edition chapbook. Marcus Amaker, the first poet laureate of Charleston, South Carolina, calls her work “equally playful, mysterious, abstract, and intimate”; he is proud to be the publisher of Kinnas’s newest collection through Free Verse Press, which he founded.

Two-time Pushcart Prize nominee Miho Kinnas recently published Waiting for Sunset to Bury Red Camellias, her third book of poetry. Her two other collections, Today, Fish Only (2015) and Move Over, Bird (2019), were both published by Math Paper Press, which is based in Singapore. Her poem “Three Shrimp Boats on the Horizon” was selected for Best American Poetry 2023. We Eclipse into the Other Side (Pinyon), which she and E. Ethelbert Miller wrote collaboratively, also came out this year as a limited-edition chapbook. Marcus Amaker, the first poet laureate of Charleston, South Carolina, calls her work “equally playful, mysterious, abstract, and intimate”; he is proud to be the publisher of Kinnas’s newest collection through Free Verse Press, which he founded.

Born in Tokyo, Kinnas has lived in Shanghai, Hong Kong, and the US. She earned an MFA in creative writing from the City University of Hong Kong and leads haiku/renku and translation workshops locally and internationally. Her poems, translations, and reviews have appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, including The Tanka Society of America, Alluvium: Literary Shanghai, Local Life, Asian Literary Journal, and American Book Review. She currently lives in Hilton Head, South Carolina, where she is active in the local community as a member of the South Carolina Arts Commission, the Island Writers’ Network, and as an organizer of a pop-up bookstore called An Island Bookshelf.

The following conversation occurred over Zoom and email in November 2023.

Renee Shea: This is proving to be a banner year for you. Waiting for Sunset to Bury Red Camellias has just been published, and one of the poems in the book appears in The Best American Poetry 2023. Earlier this year you published a chapbook. How are you feeling?

Renee Shea: This is proving to be a banner year for you. Waiting for Sunset to Bury Red Camellias has just been published, and one of the poems in the book appears in The Best American Poetry 2023. Earlier this year you published a chapbook. How are you feeling?

Miho Kinnas: I think I’m feeling the Best American Poetry effect! We had a book launch with some big-name people, like Tom Seibel, who did such a beautiful reading—and I was on the panel. My workshops are also beginning to fill very quickly, and I’m asked to blurb and review books. But I’m still processing.

Shea: When do you have time to write? As a member of the Hilton Head Masters Swimming Group, you get up at (or before) dawn to swim, and your list of community and cultural activities is daunting, yet you must have a process that’s working, despite these additional demands on your time.

Kinnas: My writing habit has been changing, depending upon what I’m doing otherwise. When there are so many events that I am reading, attending, organizing—then the time is short. Sometimes I am writing in spurts, sometimes not at all. But as far as poetry goes, it begins with the aha! moment: as long as I have that moment I can hold onto it. I think most poets need that precious epiphany, but if I write that down in my notebook and feel happy about it, it will often stay there forever. I need to keep it alive in my head and erase all the noises around the object of my moment. I should forget about the details of actual circumstances. I turn the concrete object into an abstraction at this point—it is not the thing itself anymore but becomes a representation of it—like a drawing of it. I am then free to make it cross the “border.” As the second step, I keep moving it forward / upward / downward / inside out . . .

For example, in the poem “Three Shrimp Boats on the Horizon,” the initial image consisted of a white daytime moon, seagulls, kites, cirrus clouds, and horizon. I began to deconstruct it into the elements of air and water (lights, refraction, humidity, sounds, etc.). Then these elements started to merge with my New Year “wishes.” In Japan, going to a shrine to make a wish is a common custom on New Year’s Day, and we often fly kites on that day. My mind’s ear hears the shrine bell, and the initial image crosses the border of reality and enters another sphere. That’s the “real” moment of the poem. From there, I kept moving until I came to the realization of how rare such beauty and happiness are in the actual world. And like a game of Rock, Paper, Scissors, I (or anyone) can lose it at any moment. When the “wishes” came into my poem, I dropped everything else I was doing, sat down at my computer, and finished the draft.

Three Shrimp Boats on the Horizon

Moon. White. Seagulls.

Kites. Cirrus. Horizon.

Air. Water. Wishes.

Turn. Wait. Listen.

Shades. Mirrors. Distance.

Depth. Tones. Whisper.

Prussian. Blues. Strings.

Cries. Lost. Crystal.

Rock. Paper. Scissors.

Shea: So, here you are: a well-regarded poet, translator, and teacher. But you have a BBA from Georgia State University in information systems and business (1985), and you worked in the banking/financial industry for many years. I remember hearing you explain that you wanted to be a translator, and you were advised that to translate poetry, you should learn about poetry from the inside out—that is, you should write poetry. Then (or eventually) you earned an MFA in poetry. Would you talk about what might be considered an unlikely journey?

Kinnas: Actually, there is a strong relationship between computer systems and how I think. I’m the daughter of a publisher (father) and editor (mother), so my house was filled with books. I was and still am a bookworm! I went to a university in Japan to study comparative cultures to follow my interest in the economics and history of different countries. That’s where I met my husband; we got married and his career took us to the US, where I ended up finishing my education at Georgia State University. At that time we had no money, and I had to get a job. I decided to change my major from comparative cultures to accounting or computer science; I decided to do IT plus finance. Also, because my English was not strong enough, working with computer languages and numbers was a good option for me. For the next twenty years or so I never had difficulty finding a job, whether in the US—I worked for Bell South Services [in Atlanta] for a time—or in Tokyo, Shanghai, or Hong Kong. Becoming bilingual took me a while, but being able to deal with things Japanese in English always found me a job. So that was a very good decision.

Actually, there is a strong relationship between computer systems and how I think. My poems are often organized as a relational database in my head.

My first job back in Japan was working with a relational database-management system called Ingres as the Japanese representative and systems engineer of an Alameda [California]-based software company. I trained the programmers at customer sites. The database is called “relational” because every piece of data was defined in relation to other data. These relationships involve associations and allusions that are like the elements and craft of poetry. It may sound strange, but my poetry is not language-driven. As I mentioned earlier, I begin my poems with an object and often the image or quality of it—but not a word. My poems are often organized as a relational database in my head. I suspect I am not a word-driven poet because I am constantly working in two languages without translating back and forth.

When my daughter was in first grade, I was in Hong Kong, where so many jobs involved overseas travel. So I thought maybe I could stay at home and become a translator. I took online courses at Writers.com, met several good teachers, and am still in touch with them. One, Allegra Wong, told me, “Miho, if you want to translate poetry, you have to become a poet.” I had not read American poets in English, and she recommended that I read the Vintage Book of Contemporary American Poetry. She told me to just pick someone I like and read; I chose Elizabeth Bishop—and that was pretty much the beginning.

Shea: I read in another interview that you said, “Poetry is at the center of my heart, and I live accordingly.” Was that the moment you realized that?

Kinnas: Yes. I continued translating but found writing my own poems more interesting. When my daughter graduated from high school, I started the MFA program at the City University of Hong Kong and completed it in 2014 while living in Shanghai.

Shea: What’s the synergy for you between translating the poetry of others and writing your own poetry?

Kinnas: Translating poetry is interpretation. It’s a close reading; probably the closest reader of anything must be the translator. Translation is also a collaboration with the writer of the original work. Haruki Murakami says translation is kindness. Being generous and kind to someone else’s work means doing one’s best to understand the work and present the best reflection of it in the destination language. So, at a certain point, writing and translation become one thing. What the direct influence is on my writing, I don’t know, but it adds a layer inside me. That’s something I absorb by being able to read and write in more than one language, perhaps. That’s a definite advantage. It is like having a mirror in my mind so I can see things from at least two directions. And I have access to excellent Japanese books that have never been translated into another language.

Translating is like having a mirror in my mind so I can see things from at least two directions.

What I wish to happen to the poems I translate from Japanese to English is to be retranslated into another language. It is wonderful that translators are receiving more attention these days, but so much writing is concentrated into the English language that there will be less motivation to keep other languages viable. And many languages are dying—like birds going extinct. I was very happy when a poet who picked up my book in Malaysia translated my poem into Arabic and published it in a newspaper in Yemen.

Shea: Before we get to your new book, I’d like to talk about the collaboration between you and the poet E. Ethelbert Miller. You two have written a chapbook, We Eclipse into the Other Side: Twoness Poems. As I understand it, you’ve only met once (in 2021) and began writing poems via email. Each of you writes one or two lines, then the other responds with another line, and so on until one of you feels the poem is finished. Different readers have described the process as a conversation, a jam session, a collage, improvisation, even a call-and-response. Yet writing poetry is traditionally such a solo act. How did you make this work?

Kinnas: Writing with Ethelbert is more like playing music together. It is as if we take turns and accompany each other. It is different from taking a solo in a session. Accompaniment is a better way to put it when describing our collaboration

But poets quite often write together. As I’ve said, translation is a collaboration, so to me it was a very natural process. I have collaborated with others, including Lenard D. Moore, a prolific and distinguished writer of haiku/tanka and the first African American to be elected as president of the Haiku Society of America. The style of collaboration with Lenard was familiar to me as it was similar to traditional Japanese-linked poetry.

Ethelbert and I are very different poets. He is a lyrical poet and often has a narrative line. I am more about associations, trying to find borders and jumping over them. Nothing prepared me to write with Ethelbert. Yet if you just keep writing, something rewarding always happens. In this case it’s very fast, almost a reflex, so it’s different from the usual process. You can’t go back and erase! It’s a dynamic way of writing and such a creative, learning process.

Shea: Your new book is dedicated to the Japanese poet Ikuko Tanaka (1937–2021). I assume you knew her personally, and you’ve translated her work. How has she influenced you—as poet and person?

Kinnas: She is a sister of the wife of my high school teacher. He and his wife are still very good friends of mine. I liked Tanaka’s poetry because it is set in the period of Japan I did not experience. I had lived in big cities all my life until I moved to Hilton Head. She wrote about life in a farming village, about nature, yet it is not nature poetry. Although we are both Japanese women, she had a very different life, so maybe that attracted me to her poetry. Her language spoke to me very easily: it just poured into my heart. Translating, then, was so natural. My friend Shelley Bryant, who is a professional translator from Chinese to English, helped me finish it up. I did not ask one question of the poet because I had my own understanding.

I went to visit her after I finished translating, and we spent three nights in the old farmhouse in the countryside of Okayama Prefecture where she lived and kept the house in summer; it’s too cold in winter, she said. Her sister once told me that when she woke up there was ice inside the window of their bedroom. Her mother was a talented tanka poet and briefly was part of the social circle of Yanagihara Byakuren (1885–1967), a well-known tanka poet of the modern era in Japan. However, her parents could see the war was inevitable, anticipated the worsening economy, and married her into a farming family.

Shea: It seems that your poetry has given American readers a renewed interest in haiku and tanka; one of the longest poem sequences in this new book is called “Haiku and Tanka.” Yet a number of American poets write in these forms, including Jane Hirshfield. How do you see Waiting for Sunset to Bury Red Camellias, your third collection of poetry, moving that interest forward?

Kinnas: Jane Hirshfield was a Zen Buddhist, so she knew the forms through her training. But a lot of Beat Poets wrote haiku, and I really like Kerouac’s work. He called his version “American Sentences.” When I teach workshops based on Japanese short poetic forms, I want to introduce a variety of haiku in Japanese, English, and many other languages. Lorca, for example, wrote haiku in Spanish. From the time of Basho in the seventeenth century until today, there are so many different types of haiku.

I normally start with either Kerouac or Richard Wright, who are opposites. Kerouac did not worry about syllables or anything; he went for the moment. Wright wrote thousands of haiku toward the end of his life when he was very ill and lonely. Interestingly, he kept the 5-7-5 format pretty diligently.

People come to my workshops because they want to know more about haiku, so they get that information. But what I really want them to think about is not the 5-7-5 structure, written only about nature or a season. With so many writers doing different things, we have that freedom to learn from what other people do with haiku without calling themselves a “haiku poet.” I also ask people to link each other’s poems or write ekphrastic haiku—not simply to describe a picture but to show an oblique relationship with the picture. That association is what most interests me in poetry, and it needs to be a surprising association. Haiku is such a good vehicle to use: it’s so short, and you have to make it really compact, to hone in on what it is you want to say.

Shea: Many of your poems, and not only haiku or tanka, are either quite short or not more than a page. I think of “Spirit,” a striking poem that is like a still-life painting:

With a huge freezer, a widow

moves into an apartment. To open

she transfers the bowls and plates

off the freezer. To find

the lemon cake her husband loved.

A bag of peas burns her fingertips.

After closing the lid, she moves

the plates and bowls back.

The material objects themselves are so concrete, so ordinary, yet tenderly evocative of deep emotion. As you were writing this one, for instance, did you move the words around, arranging and rearranging like the objects themselves?

Kinnas: My words are concrete, but my poems are quite abstract. I try not to use many adjectives or adverbs. I want my poems to be filled with images—even smell or sound to be shown as an image. To me, haiku is filled with an image of concrete things, but you have to find a way that even this little pebble becomes something else, a different dimension. Also, most of my poems are “nonfiction,” as this one is; I was watching my mother-in-law after she lost her husband.

Shea: In Red Camellias, even more than in your other books, the physical form of the poems on the page is fascinating and feels integral. In an email exchange, Marcus called your use of white space “masterful.” In fact, he commented that it wasn’t just the poetry itself but his graphic-design eye that drew him to the collection. Elaine Equi, the guest editor of The Best American Poetry of 2023, noted that “Three Shrimp Boats on the Horizon” can be read horizontally, vertically, even diagonally, resulting in “building blocks with which we can construct our own meaning.” How does the form on the page influence meaning in your poetry? I’m not certain, for instance, whether to think about “Haiku and Tanka”—which is several pages—as one long poem or a sequence of poems.

Kinnas: In “Haiku and Tanka,” I intended to spread them [the poems of these two forms] around. They’re family poems, love poems, historical poems, but I did not like any logical sectioning. I don’t write in themes, but every poem sounds very much like me, so I just keep reading and connecting until I find a flow. It’s hard to explain.

Shea: What about “A Breath in the Wind”? The words in the left vertical column are reversed in the right column, with the word “music” in the center of both?

Kinnas: I was doing a yoga class where the teacher used a gong and a lot of chanting with very simple movement. I was pretty down that day, and the class really lifted me. So that’s the experience: I was kind of floating, and the music in the middle was exactly how it felt. I just kept playing with it.

I was kind of floating, and the music in the middle was exactly how it felt.

Shea: You’re describing such a specific context in many of these poems. Yet in a blurb for Red Camellias, the poet and teaching artist Arlene Naganawa wrote, “The reader is always invited into the poems as a participant and guest.” What do you hope readers will take away from your poetry?

Kinnas: Sometimes I feel that with narrative poetry, you just listen and understand immediately, but my poetry is not that. I am asking people to come in and have their own thoughts. I have my thoughts in my head, but I do not want to present that. I want each reader to come to my poetry to feel something. Everyone lives in a different situation and background, so even if I write something concrete, some who live in different parts of the country or speak in a different language—they will have a different experience. And I want them to make it their own.

Three Poems by Ikuko Tanaka (1937–2021)

translated by Miho Kinnas & Shelly Bryant

Preserved Morning

That morning is preserved in the kitchen of the old house

I was in middle school shortly after the defeat of our country

It was a snowy morning and food and clothes were scarce

My mother was cooking rice in the kamado vessel

She was crying in front of the bursting flame

I didn’t know why

My father was pacing a little distance away

Later that day, my father returned from the mountain with a pheasant

When I touched the dark green feather it was still warm

I watched how my father plucked the bird

Meat was so rare we even crushed bones and rolled it into balls

My mother dug out a daikon radish from the snow field

and placed charcoal on the shichirin stove

I still didn’t know what the argument in the morning was about

but my stomach went on and was filled

Though the memory of the war fades it doesn’t disappear

Every time I let my body sneak into the preserved morning

the fire starts in the cracked kamado vessel

I sense both the woman who cried and the man who paced

scurry away

The sensation, however, is entirely mine

Falling into the Body

The magnolia is in bloom

but snow keeps falling into my body

Photographs always capture those who depart

On the edge of the yard of the remote place

Six of us stood in a line as our father

was drafted at the age of thirty-one

The picture of the family dressed-up in haste

I see we wore ordinary expressions — we didn’t see anything alarming

Grandparents, parents, my sister and I

Only I have survived since

The magnolia is in bloom again

but snow keeps falling into my body

In the wind of a worrisome season

The sound of my shoes pressing the new snow

Pear blooms, peach blossoms, rice ears bend

Half moons and full moons flow down the valley water

Carefully studying the family in the photograph

I now see the magnolia tree swaying behind us

We didn’t know but it was waving a good-bye

We were not meant to see

In the Wind of Bleached Memory

One day, after the wind, my father was on the battlefield

One day, after the wind, my father was a returned soldier

He came home to the dirt yard of the narrow land in the mountains

His body was thin and his face tinted yellow

I peeked at him from behind my mother, I was told

He, in my memory, was always sick

An egg, he ate, threw up and lost in diarrhea

A piece of fish, he ate, threw up and lost in diarrhea

His body diminished

One day as he hurt his spine in the forest

One day he lost consciousness under the falling tree

He didn’t talk about the battlefield

When the rough wind blew

he saluted with a stern expression

shouted, stammered and I heard the slapping of the cheeks in the dark

On another day whatever the wind blew

he raised his hand high with a chess piece between the fingers

then thwacked it down and that made him smile

He fished a trout he kept in the pond and that made him smile

And then, with Huntington’s disease, he grew thinner and his hands trembled

And then, he was stung by an October bee and died at the age of fifty-eight

One day, in the wind of the bleached memory

I was a middle school student

“Democracy” was brand new

“America” was brand new

I stood by the window and my father said to me

“Girls are better off not reading newspapers”

I wondered what he was still fighting against

His voice was very low

It has been sixty years

The voice and meaning fade away

I stand in the dirt yard — nothing has changed there —

I stand by the window where I faced my father

In the space between the feeble light and the warmth of blood

I place the printed word “Peace”

In the light, in one sliver of light,

the image of my father doesn’t come together

because it doesn’t — I think

I will carry with me the space by the opaque window

of the abandoned house

The eyes of the battlefield seemed gentle

They might have been lonely just as

the wind, the light and the shadow are

Translations from the Japanese

Editorial note: From The Song of Rowanberry (Ono Tozaburo Prize, 2007), by Ikuko Tanaka. Published by permission of Miho Kinnas.