Patience, Perspective, and the Power of Story: An Interview with Toni Ann Johnson

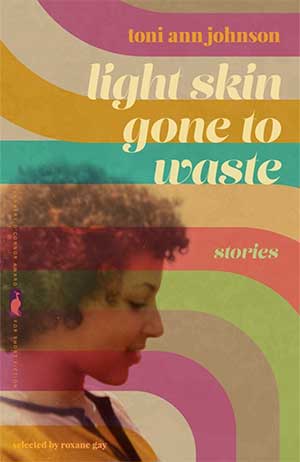

Storyteller Toni Ann Johnson uses her skills as an actor, playwright, and fiction writer to tell powerful stories of race, reconciliation, and the effects of lingering racism. She is award-winning on stage and screen, most recently with her story collection Light Skin Gone to Waste (University of Georgia Press, 2022), selected for the 2021 Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction. When I spoke to Johnson in Los Angeles and later by email, we explored the role stories can play in our understanding of truths, including matters many would rather forget.

Storyteller Toni Ann Johnson uses her skills as an actor, playwright, and fiction writer to tell powerful stories of race, reconciliation, and the effects of lingering racism. She is award-winning on stage and screen, most recently with her story collection Light Skin Gone to Waste (University of Georgia Press, 2022), selected for the 2021 Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction. When I spoke to Johnson in Los Angeles and later by email, we explored the role stories can play in our understanding of truths, including matters many would rather forget.

Scott LaMascus: If you were joining the late Flannery O’Connor on her porch in Milledgeville, Georgia, what do you hope she would praise about your stories that were honored with the award named for her?

Toni Ann Johnson: I wouldn’t expect Ms. O’Connor to praise my stories. Her racism would likely have prevented her from appreciating their subject matter. In her letters, she wrote:

About the Negroes, the kind I don’t like is the philosophizing prophesying pontificating kind, the James Baldwin kind. Very ignorant but never silent. Baldwin can tell us what it feels like to be a Negro in Harlem but he tries to tell us everything else too.

O’Connor was put off by James Baldwin’s writing because it dared to stray beyond the confines of being Black in Harlem. So I imagine she’d eschew Light Skin Gone to Waste, which is about Black people who refuse to live according to narrow, bigoted ideas about what they should be or do or have. In her letters (made available to scholars in 2014), she said she was repulsed by the sight of Blacks and whites sitting together. It’s unlikely I’d be welcome on Flannery O’Connor’s porch.

LaMascus: What might you ask O’Connor? What might you tell her?

Johnson: I admire and celebrate Ms. O’Connor’s immense talent and achievements as a writer and as a woman in a patriarchal culture, and I’m profoundly grateful for the prize that bears her name; however, she’s not someone I’d seek to be in conversation with. I reject her inability to see Black humanity. I spent my childhood engaging in the futile effort to prove my humanity to those who refused to acknowledge it. I have no further interest in that endeavor.

In this hypothetical visit (which I would not subject myself to), I might ask Ms. O’Connor if her views had evolved. I’d tell her I was inspired by the quality of her prose, intrigued and entertained by some of her characters, and admired the way she structured her short stories, but that I stopped reading her work because her characterizations of Black people wounded me. I’d tell her that the fact that a Black editor was able to choose a Black writer for a prize in her name was, in my opinion, a kind of redress for the racist ideas she promoted in her depictions of Black people.

I spent my childhood engaging in the futile effort to prove my humanity to those who refused to acknowledge it.

LaMascus: You have talked about the long gestation of these stories and your decision to submit them to O’Connor Prize judge Roxane Gay for consideration, about the work of cutting down an unpublished novel, shortening the manuscript to fit contest restrictions. As an author, what goes into that kind of perseverance, flexibility, and grit to see a work into print over all obstacles?

Johnson: Grit is the right word for it. The novel version of Light Skin Gone to Waste was twice the length of the published version. I conceived the book as a story collection. The first few stories I wrote got the attention of a literary agent who took on the project. When I delivered a first draft, the agent decided that rethinking the collection as a novel would make it more appealing to publishers. I didn’t understand the vision and didn’t want to revise it as a novel, but I wanted to sell the book. Turning what was a collection into the agent’s vision of a novel took multiple drafts and five arduous years. When, after all that, the book failed to sell, I was devastated and angry with myself for not trusting my own instincts.

Johnson: Grit is the right word for it. The novel version of Light Skin Gone to Waste was twice the length of the published version. I conceived the book as a story collection. The first few stories I wrote got the attention of a literary agent who took on the project. When I delivered a first draft, the agent decided that rethinking the collection as a novel would make it more appealing to publishers. I didn’t understand the vision and didn’t want to revise it as a novel, but I wanted to sell the book. Turning what was a collection into the agent’s vision of a novel took multiple drafts and five arduous years. When, after all that, the book failed to sell, I was devastated and angry with myself for not trusting my own instincts.

I knew the reason the book hadn’t sold as a novel was because it was not a novel. It was episodic by design. I returned to my original vision for the book. I was going to submit a version that included the novella Homegoing as the last story, but the word count limit forced me to cut it. (Homegoing was already set to be published by Accents Publishing in May 2021, the same month I submitted to the Flannery O’Connor Award.)

I submitted what I had, feeling that it probably wouldn’t win, but I hoped Roxane Gay might like my writing enough to be open to reading another manuscript for her imprint at Grove Atlantic. I was surprised to learn that a collection I worried wasn’t quite complete could win. I was also gratified that all the energy I put into the work during the five years of development was not, after all, for nothing.

LaMascus: What advice about the rigors of publication would you give to other writers?

Your grit develops as you fail, and lose, and refuse to quit.

Johnson: I would say: Have more patience than you think makes sense. You have to hang in there and not give up. You must keep writing, improving your work, and submitting. You can’t let yourself be defeated by rejection. On my first book, I gave up the agent search after only a few agents passed. Writers need grit. Your grit develops as you fail, and lose, and refuse to quit.

The launch of my screenwriting career might be considered easy because it happened after a play I wrote and acted in landed in the hands of an entertainment attorney who subsequently shared it with agent Dave Wirtshafter, who read it, liked it, and signed me. From that point on, studio executives and producers were willing to work with me because of Wirtshafter’s reputation and because I had a specialty: writing about race and race relations.

It was a confluence of good fortune, but I was truly struggling by the time my break into the entertainment industry came when I was thirty. I’d been studying acting from the time I was twelve, and I began writing plays at nineteen. I’d written many things that went nowhere. What might have appeared to be a lucky break was the result of years of preparation, dues paying, and financial difficulty as well as a lot of mental determination.

LaMascus: Why have you pursued not one but several genres in your storytelling: short story, playwriting, screenwriting? Was that a purposeful choice? Do different stories call for different frameworks?

Johnson: As an acting student I was constantly reading plays, so that was a format I grew familiar with. When I started looking for acting work, I didn’t look identifiably Black to the theater world, and I realized I needed to develop material for myself. That’s how one of my early plays, Gramercy Park Is Closed to the Public, developed. A film producer submitted the play to the Sundance Screenwriter’s Lab and I was accepted.

Shortly thereafter, Wirtshafter launched my screenwriting career with that play, arranged a staged reading with me in the lead and Della Reese playing one of the main roles, and I began taking meetings for open writing assignments. I did that for over a decade. After ten-plus years of executing other people’s ideas, I got tired of writing for hire and wanted to get back to my own voice—the voice I had found as a playwright. But I didn’t want to study playwriting as I had in New York, so I focused on fiction, which led to my getting an MFA in creative writing. When I began studying the art of fiction, I loved it and knew I could spend the rest of my life getting better at it.

LaMascus: You have been extremely productive in storytelling—on stage, on screens large and small, and in print—across changes in how audiences, publishing, and media operate. How are these changes shaping your emerging work?

LaMascus: You have been extremely productive in storytelling—on stage, on screens large and small, and in print—across changes in how audiences, publishing, and media operate. How are these changes shaping your emerging work?

Johnson: I’ve been focused on fiction—out of the film and TV world—for a while. Because I’m not writing for hire, the changes in audiences and media don’t affect what I’m writing. I write about the characters, themes, ideas, and circumstances that interest me. I don’t chase trends.

LaMascus: Your latest book tells the story of racial and cultural reconciliations in a New York neighborhood. It speaks to our times of decreased social mobility and increased social disparity. The plots and characters seem to strike at the very heart of the lie that the U.S. has no class system. Your characters live with the implications of class in interesting ways—as social climbers, those born with status, or those who protect the privileges of status. What do you hope Americans learn about class from these stories and characters?

Johnson: I’m astonished by the idea that there are people in this country who think we have no class system. Poor people and people of color of any socioeconomic background have always been aware of class structure in America. I think most white people, too, whether poor, middle class, or wealthy, are aware of class in this country. The hierarchy may be tacit; however, it’s understood that Black people are implicitly at the bottom or near the bottom.

What my book expresses with regard to class is that some Black people can be and have been more educated and more affluent than some white people. There has been a class stratification among Black people in this country that preceded the Civil War. In the 1960s and 1970s the dominant culture did not seem aware of this. By and large, the culture was oblivious to the Black elite and the Black middle class and seemed to believe that all Black people were low-income and had low intellectual aspirations. Even into the 1980s, when The Cosby Show aired, the prevailing perspective was that Black high achievement and affluence was a fantasy, not a reality within the Black population.

It never was a fantasy. Black professionals existed. Before white universities accepted Black people, there were Black universities educating doctors, lawyers, teachers, architects, artists, and other professionals. There has been a Black elite for hundreds of years.

In my book, I focused on a specific time, midcentury, when the majority of white people in my town had little exposure to affluent, educated Blacks and, in fact, did not believe in their existence. They had trouble seeing me because they had no frame of reference for me. I would have welcomed the opportunity to grow up knowing families similar to mine.

I wrote the stories to show readers a Black family they’ve likely not seen before. My family, on which the Arringtons are based, was not of the Black elite. My parents came from middle-class families. My father felt rejected by the Black elite as a young adult who didn’t come from wealthy professional parents, and, ultimately, he chose to separate from the Black community in favor of a White one.

LaMascus: Which author has most influenced you most?

Johnson: James Baldwin. Kiese Laymon wrote that you have to read books at least twice to have really read them. I’ve read all of Baldwin’s novels and stories and most of his nonfiction books at least twice. I’ve read Another Country and Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone a few times. The characters and their world are familiar to me. I feel at home inside those books. I related to them. I admire Baldwin’s voice and am awed by the way he layers in his analysis of social problems. I reread a lot of his work in 2020, and it was astounding and sad how relevant it remains. Everything Baldwin writes about American racism is still extant today.

LaMascus: Congratulations on your teaching role at Antioch University. Antioch’s mission statement emphasizes social justice. How does your writing figure into Antioch’s emphasis on “advancing social, economic, and environmental justice”?

Johnson: I often write about race relations. I’ve done so in movies such as Ruby Bridges (about integration) and Crown Heights (about tensions between disparate communities). I also examine race relations in my stories and novels. I try to express the full humanity of characters of all races. The goal is to foster understanding of one another’s perspective, to increase empathy, and to move toward harmony and social justice.

The goal is to foster understanding of one another’s perspective, to increase empathy, and to move toward harmony and social justice.

LaMascus: What overarching message or goal are you seeking to accomplish in your work?

Johnson: It feels limiting to define one’s work in those terms. But if I look at the body of what I’ve written, it seems that I’ve been examining race and class with the kind of complexity that I observe. I’m always looking for contradictions to what’s expected or assumed about the characters I write.

I grew up in a racist culture that, as I experienced it, looked for easy ways to define people. I’m drawn to the complicated, the unusual, and the unexpected, and so I’ve tended to write about the humanity of people who have stepped outside the parameters erected by the society they live in.

Editorial note: Published in partnership with Oklahoma Humanities magazine (okhumanities.org).

Toni Ann Johnson is the author of the novella Homegoing and the novel Remedy for a Broken Angel, which earned an NAACP Image Award nomination for Outstanding Literary Work by a Debut Author. She is a two-time winner of the Humanitas Prize for her screenplays Ruby Bridges (for Disney) and Crown Heights (for Showtime). Her essays and short fiction have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Hunger Mountain, Callaloo, and other publications. Johnson holds an MFA in creative writing from Antioch University Los Angeles and a BFA from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts.