“Fictions are concentrated in the library nurtured by AI”: A Conversation with Jorge Volpi

Since the moment we became readers, we have always thought that to interpret the most profound ideas of a literary work—from the multiple creations of scientific theories to the perpetual scenarios of fiction, passing through other parallel universes such as philosophy or music—we should have an infinite number of pages in a novel whose center could always move, in a pendulous way or, perhaps, indeterminately. However, Jorge Volpi’s La invención de todas las cosas (The invention of all things: A history of fiction) allows us to pause in detailed accounts of human scholarship and then multiply the doctrines narrated since we live far beyond the pages of a book.

In this novel, we can build and deconstruct a fantastic reality full of great scientific discoveries, enormous enemies of freedom, and feverish erotic or religious markets. We learn about beings, organisms, species, and progeny that inherit the favorable variations of their parents, lives directed by morality or theological guidelines that always appeal to the need for survival.

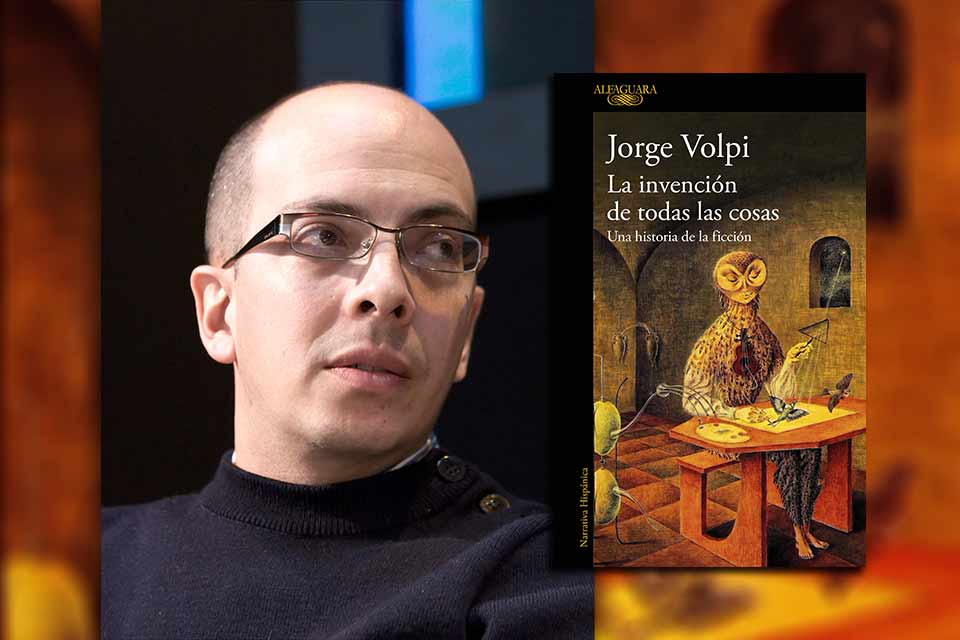

“All I am is literature,” says Kafka in the epigraph, while Remedios Varo’s painting Creation of the Birds illustrates the cover as an admirable visual prototype. Within, multiple chapters include reflections describing Giotto’s Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple, Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, Francisco de Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, Pablo Picasso’s Woman with a Mustard Jar, Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, René Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe, and a varied succession inherited from the visual, including Pere Borrell del Caso’s Escaping Criticism. Leading us among the high-sounding consequences of existence, using words and pictures, Volpi gives us an indelible image of origins to arrive, after multiple twists of history, to the evolution of experience, of the vision of a world where the superego, ego, and id question the values and free the imagination from its immense prejudices.

Claudia Cavallin: I want to introduce your novel with the shocking theory of the Big Bang. There is an unstoppable explosion that allows us to continue expanding any limit of that space filled with tiny particles. You mention Copernicus’s challenge, which inspired those of Bruno, Galileo, Brahe, or Hawking. Thinking of a book as the representation of an unlimited universe: When did you make that explosive connection with your mind that encouraged you to write The Invention of All Things?

Jorge Volpi: If I look for the remote origin of The Invention of All Things, I will find it in my amazement at Carl Sagan’s Cosmos at the age of twelve. Later, in reading Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Gold Braid, by Douglas Hofstadter. Then, in my immersion in fiction, I think the theme of all my books is, deep down, the tension between truth and lies, reality and fantasy, which led me first to write Leer la mente (Read minds) and now this new book.

Cavallin: An immersion that can make us wake up like a monstrous Kafkaesque bug or always leads us to think about who we are: a dream of others, as in Borges’s stories, or whether we exist or lack the certainty of existence. Your book emphasizes that fiction comes “from the Latin verb fingere, which does not mean to pretend or deceive, but to carve or model.” What would be—metaphorically speaking—the figure of the world that you are carving for us? What do I have in my hands now from reading your book?

Volpi: To be consistent with the theory of the book itself, The Invention of All Things is, first of all, fiction. The deceit that it is possible to write a history of fiction (and, incidentally, a theory of fiction), which extends from the moment when there was no consciousness in the universe to create fiction until the appearance of life on a small planet in a peripheral galaxy, and from there throughout the entire history of humanity, even reaching our images of the future—of the end of life and the inevitable end of the universe.

Cavallin: Before reaching the end, between the pages of your book, myths, religion, philosophy, astrology, art, writing, comics, and video games are connected, all the things humans have created to make sense of our world. If we want to live in that universe—the one, Borges points out, that others call The Library—is it necessary to remain silent to understand it? Is it essential to stop, continue weaving, or unweave what we create to analyze that wonderful space in which we live?

Volpi: We are fictional and narrative beings. No matter how much we seek silence—or the emptiness of the Buddhists—our brain architecture leads us to a welter of fiction and stories from which we cannot escape.

Our brain architecture leads us to a welter of fiction and stories from which we cannot escape.

Cavallin: Let’s go back to another story in your book. In “Sobre cómo desatar una epidemia: El nuevo testamento y las confesiones” (On unleashing an epidemic: The new testament and confessions), you mention that “Jesus is a great oral storyteller.” His parables are also paradoxical fictions designed to unleash empathy. Here, words can be read as political stories, denouncing “the unequal distribution of power.” Moving to our current world, to dissemination on networks, to “orality” on the internet, how is current inequality structured from the spaces shared on social networks?

Volpi: Our fictions result from this double tendency of our animal nature: we are the most violent and, at the same time, the most cooperative primates. Inevitably, most of our fictions reinforce one side or the other. And that is why fiction has served, especially since we became sedentary, to justify and establish the division of power (always inequitable) that has existed in our societies. In our time, which is still fiercely neoliberal, a good part of our fiction accentuates and justifies these immense inequalities. Social networks are their greatest disseminator, mainly because, for the first time in history, anyone can replicate these fictions from the comfort of their pocket computers (which we continue to call phones), looking for the broadest possible audience.

We are the most violent and, at the same time, the most cooperative primates.

Cavallin: When you mention the wonder of art, you point out that Michelangelo’s painting The Creation of Adam (1511), where the hand of the creator and his creature do not touch, represents that instant of creation in which the imagination and the imagined try to connect. Is our imagination, including those “caricatures of ourselves that amaze and horrify us,” necessary to carry out a catharsis? Do we exist strangely, without touching each other, to strengthen our purification in the face of all passions?

Volpi: I believe that reality exists, but our only way to approach it is through fiction. Reality includes, of course, the others whom we can never touch but only imagine. That void between one and the other is both disconcerting and atrocious: that is why our love fictions seek to assume that it does not exist.

Cavallin: Love fiction, those that create a map of affections. In “Sobre cómo acariciar el absoluto. Kant, Hegel, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche” (How to caress the absolute: Kant, Hegel, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche), you mention truth, ethics, morality, and humanity. The concept of individuation is sometimes necessary. How do you achieve that emotional balance through music? And, in doing so, what should we never stop listening to to preserve the musical moderation of the absolute?

Volpi: Music is perhaps the most mysterious of our fictions—and the one I am most passionate about—because we can almost never transform it into coherent concepts or stories. Almost purely emotional, fiction enraptures us and separates us from ourselves. As Cioran explains in All Gall Is Divided, “Defenseless against music, I must submit to its despotism and, depending on its whim, be god or garbage.” Music turns us into garbage, emotional slaves at its service. I don’t know if this makes us more balanced or the opposite, but it is still one of the greatest human inventions.

Cavallin: I want to close this universe of sensibility with contemporary art, especially Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe, which I see while we talk. In your words, contemporary art became just another area of fantasy literature, “a story that only exists in the brains of artists and spectators.” There is a duplicated existence in the duplication of letters in Samsa and Kafka. In the stubbornness to break the ambiguity. In the conjectural nouns of “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius.” In the holograms of the future. Where is art headed? Will we all arrive at that Macondo or MacOndo which, perhaps, awaits us just around the corner?

Volpi: It is difficult to say where artistic fiction will go in the future. We have the impression—but perhaps it has been so at many other times—that we have reached the limit and are doing nothing but repeating ourselves. That may be why there is astonishment and fear in the face of artificial intelligence: there, despite everything, is something that we have not seen until now. Without direct control, all our fictions are concentrated and scrambled in the vast human library from which AI feeds. Will anything new be found there? We’ll see.

Translation from the Spanish

Jorge Volpi is a Mexican author of novels and essays. He studied law and literature in Mexico before earning a PhD in Spanish philology at the University of Salamanca in Spain. His passion for physics inspires him to present modern science’s history narratively. Volpi has received grants from the Guggenheim Foundation and has been a member of the National System of Creators in Mexico.