The Consequences of Story: A Conversation with Manuel Muñoz

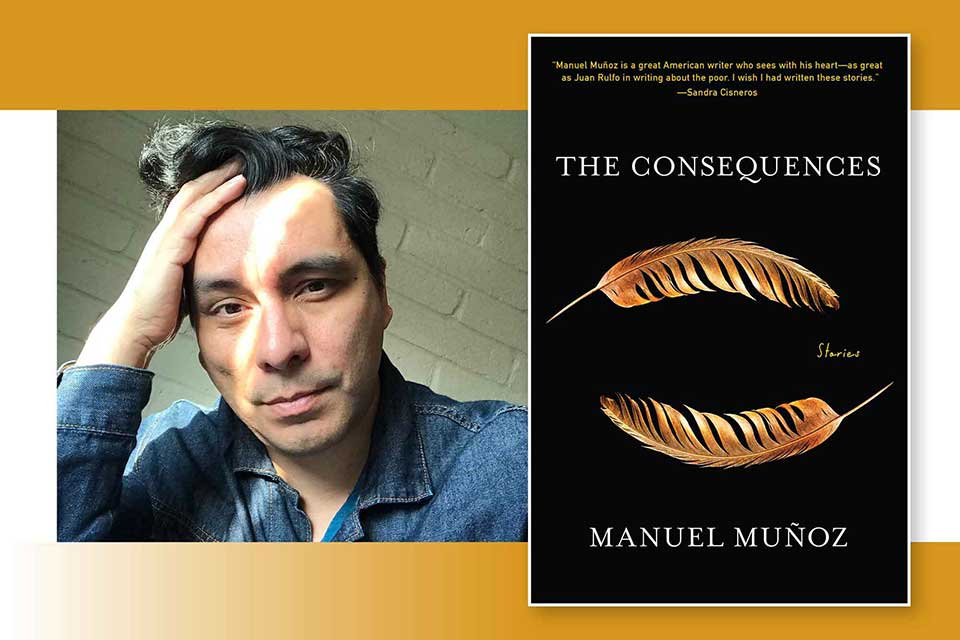

In The Consequences (Graywolf Press, 2022), his third collection of short fiction, Manuel Muñoz continues telling the stories of migrant workers, seekers, and dreamers in the Central Valley near Fresno, California, where he was born and raised. After high school he left Dinuba, his rural hometown, for Boston, where he received his BA from Harvard University and then pursued his interest in English and creative writing in the MFA program at Cornell University. After working in publishing on the East Coast, he accepted a position in the Creative Writing Program in the English Department at the University of Arizona in 2008, where he continues teaching and writing.

Muñoz received praise for his two previous collections, Zigzagger (Northwestern University Press, 2003) and The Faith Healer of Olive Avenue (Algonquin Books, 2007), which was shortlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award. His stories have won three O. Henry Awards. His debut novel, What You See in the Dark (Algonquin Books, 2011), is a mystery set in 1950s Bakersfield, California, with the filming of the movie Psycho as backdrop. In his frequently anthologized essay, “Leave Your Name at the Border,” he explores the anglicizing of Mexican names.

Muñoz’s mentor at Cornell, writer Helena María Viramontes, is often called his “literary godmother.” She describes him as having “a very radical talent with a sense of values that nobody can teach, a way of feeling injustice in his own bones and having the strength and morality to do something about it through literature. With The Consequences, he has hit a stride of confident, quiet authority.”

*

Renee Shea: Wikipedia, which usually identifies the names of parents, says only that you “were born into a family of Mexican farm workers.” You’ve remedied what might be seen as an oversight in your dedication to The Consequences with their first names: Esmeralda and Antonio. Shall we go further and provide full names?

Manuel Muñoz: Antonio Morales and Esmeralda DeLeon Morales. In fact, he is my stepfather, but that’s not who is he is to me. I’ve written an essay recently about why I just simply call him my father. My biological father—I won’t name him because he was not really in the picture—left my mother with five kids about a month after I was born. She met Antonio when I was about four or five years old, and that’s who I have always seen as my father.

Shea: The epigraph to this collection is five lines from a poem, “Fantasy and Science Fiction,” by Rita Dove, but I’m not sure how they speak to you about what you’re doing in these stories.

Muñoz: It’s a nod to how I have received stories from my parents, but, I, in turn, have not really shared any of my own. It’s well understood in my family that I’m out, but we don’t talk about it. All of the personal stories of mine about love or rejection or partnership aren’t shared or even asked about. That’s not what the Dove poem is actually about, but the lines struck me: the privacy and intimacy of encountering or experiencing story: “shutting a book . . . you can walk off the back porch / and into the sea—though it’s not the sort of story / you’d tell your mother.”

Shea: Yet you go back to Dinuba frequently, and from the story Helena recounted about your mother cutting holes in your jeans to remind you that there was another life out there for you, I’d say your family must be very proud of your education and achievements.

Muñoz: I do go back home quite a bit because everyone still lives there. When I got this job in 2008, the twelve- or thirteen-hour drive made it easier than crossing the country where I had been for eighteen years. And, yes, that story is true. As grade-school kids, we were in charge of spreading the freshly picked grapes out on paper for drying into raisins, so we were constantly kneeling in the dirt, and, of course, we hated it. There were already holes in my pants, but my mother made them bigger so that when I bent down, I’d feel the hot soil. It may sound cruel to some—tough love!—yet she saw the potential for our cycle of poverty staying in place. That was her way of saying there was a way out: the ticket was school. I’m still astounded that my parents let me take that risk of leaving the fold—all the way across the country.

Shea: I’d say the risk paid off, and maybe we have your mother to thank for The Consequences. It’s such a provocative, even unsettling, title. When did you realize that the one story (“The Consequences”) had a larger resonance to become the title of the entire collection?

Muñoz: I’ve been pretty open with friends and colleagues that this was a very tough book to write—it took me nine years, so I’m eleven years between books. I was very confused about the reaction and expectations to my work, particularly to the novel. I wasn’t sure where I was going in terms of the literary world, if it was still worth the time to keep producing. When I returned to writing short stories, it was not necessarily a source of comfort, but it was something I knew I did very well. “The Consequences” was maybe the fourth or fifth story I had written, not really with a book in mind, just simply writing without burdening myself with a book or project.

When I meditated about what the next story might be, I kept coming back to what people would say when I did a reading or had a conversation at a college—that I wrote about “aftermath,” about what happened after a big event. They often asked, “Why don’t you tell us about the event?” I didn’t quite have an answer, but I think that’s what got me to that word—consequences—because it suggests there’s a whole other story after an event, how people deal with a trauma or loss or even something joyful. “The Consequences” as a phrase became a touchstone for me. I realized this is one of the things that could help me move toward a collection.

Shea: In each of these stories, there seems to be a decision (not always one well considered), a kind of inflection point. Is that what you meant in an earlier interview when you said, “My characters tend to think rather than act”?

Muñoz: I’m also thinking of the difference between acting and reacting, even overthinking something. That’s where memory or regret might come into play. Other times, a character might act in the moment and recognize how momentous it is to do so. I’m thinking of “The Happiest Girl in the Whole USA.” It seems like it’s a spontaneous gesture to give the woman some money and shoes, but I want to say that this impulse to help somebody else has always been there in the character as much as she claims to hide it and be stern with herself and others.

Shea: The stories in Consequences share a setting; some characters move from one story to another; themes of visibility and invisibility, secrets and lies run throughout. How do you see this collection as a unified book of interconnected stories?

Muñoz: Right now, I’m using Edward P. Jones’s two short-story collections [Lost in the City and All Aunt Hagar’s Children]. I have my students read the paired stories drawing from each book, and sometimes they look for the same characters or situations, but then I ask them to think about the ways that seemingly disconnected stories can be part of the same world.

At least for me, knowing that so many of the stories take place in such a small town, it’s inevitable that people will know one another. I was doing this in my other collections—readers might notice that the person in the red pickup truck in one story shows up in another—but I never really allowed seemingly minor characters to have their own storylines. In these stories, I stayed true to my mantra to my students, “If you put somebody in a story, no matter how minor, then they’re important.” I tried to keep my attention on each story, but I kind of thought of them as templates: “You did a story this way; see if you can do it in a different way.” Teo, for example, came first in “The Consequences.” But it’s when I went back and reread the story that I kept asking, Who is he calling in that family? Who is the voice who finally answers the phone? That’s how the character of the sister shows up in the final story, “What Kind of Fool Am I?”—a different point of view. There’s something liberating about trusting the story once I finish it to be more than it is.

In Faith Healer, where a character is driving down the street and counts the houses along the way—I think the number is fifty-seven—he deliberately thinks about the multiplicity of stories, all of those people, all those relationships, whether they’re private or shared. I’ve expressed doubt about the writing, but when I sit back and think about the incredible permutations of story, it gives me a little more ánimo, as we say in Spanish, a little more get-go to keep writing. There’s more to say, more to observe, more people to write about.

In these stories, I stayed true to my mantra to my students, “If you put somebody in a story, no matter how minor, then they’re important.”

Shea: I want to talk a little more about timing. Your three earlier books came out fairly close to one another, about four years apart. Then it was about ten years until The Consequences. I’ve read that you overcame what you’ve called a “crisis of confidence” about your writing until an Italian publisher, Edizioni Black Coffee, reached out after an editor read the story “Susto” in a literary journal. I’m a little skeptical that this one positive gesture had such a magical touch. True?

Muñoz: It wasn’t just a response to one story: Sara Reggiani, the editor, wanted a whole book. She was astonished by the story and asked Stuart Bernstein [Muñoz’s agent] if she could read the rest—and she made an offer to publish it before I was done. At that point, the relationship with Algonquin was over, and I knew I had to start out again. I thought, Why not publish overseas? If they’re interested and recognize something in it, why not see how far you can go on the fumes of that excitement? It lit a fire. I was moved by it. She also asked, “Why haven’t I heard about this guy before?” That felt really good. By that point, I was five or six stories in—and I started thinking about this as a book, not just a collection. Then I began editing, arranging, considering pacing and where the stories would go against each other. That process affected the kinds of notes I wanted to hit with those last few stories that I had yet to write.

Shea: I’d like to talk about a specific passage: the opening paragraphs from “What Kind of Fool Am I?”—the final story in Consequences. A little bit of context is that this story returns to the character of Teo in “The Consequences” from the point of view of his sister.

Listen to the author read the opening paragraphs from “What Kind of Fool Am I?”; scroll down to the bottom of the interview to read the passage itself.

Shea: That last line is so great: “. . . his impatience ran him away.” You seem to understand that feeling because every one of these stories has at least one, maybe several characters, who are impatient in different ways.

How does someone, a character, take steps to make a story come to fruition, regardless of whether that story is even possible?

Muñoz: “Impatience” is a complicated word. “Impatience” starts to suggest the story you want to happen but won’t happen because you live in a place where it can’t happen. There’s a relationship between impatience and the consequences. How does someone, a character, take steps to make a story come to fruition, regardless of whether that story is even possible? The way I talk with my students about story construction starts with asking, What does the character want? The conflict is the wish for this thing to appear, but sometimes it’s a hard place for those dreams to come true.

Shea: Later the narrator says, “There was no place I could think of in town where I could be out and not be seen by someone.” This tension between being under scrutiny in your own community, yet invisible in the larger society, seems something you keep exploring or interrogating through any number of these stories. Is that right?

Muñoz: That paradox is incredibly fascinating. There’s the sense in a small town that there’s nothing to do, but the moment you do it, everybody witnesses it. Not only that, they may witness it from a distance or somehow misinterpret it.

Shea: Even within this story—which begins with that provocative declaration, “I lied to myself all my life” and focuses on Teo and his sister—there are other stories that remain untold but are potentially stories within the stories: the women at the five-and-dime, for instance. That possibility, or promise, is really quite wonderful.

Muñoz: It goes back to my parents—they’re fantastic storytellers. The thing about it is even when we’ve heard the same story many times, we know not to interrupt. They can be interrupted with reaction like disbelief or laughter, but even if I have a question, I realize that I don’t ask that question until I know they’re done. They taught me to listen—to be patient enough to listen—so that maybe later on, I can retell the story with that kind of hook because I know what it is that creates a question to the one who’s telling the story.

Shea: So many of these stories are about storytelling itself. In “Fieldwork,” you wrote about the elderly men: “. . . their bodies had given out. But their minds hadn’t. Their stories were not yet lost in their heads.” Is your intent to find and keep—and honor—them? In an interview in Contemporary Literature, you said, “If you don’t tell your story, someone else will.” I don’t mean to overstate it—but you seem to have a kind of sacred trust that you are telling stories of people who do not or cannot tell their own stories, and you are keeping them from getting lost.

When something is passed down in some way, that in itself is precious. It is sacred.

Muñoz: Thank you for phrasing the question that way because sometimes when I enter discussions about who’s telling the stories, I think there are some good hesitations and boundaries we have about who’s speaking. But when we’re too cautious with that idea, that’s the potential for the loss that something won’t be remembered or recorded. When something is passed down in some way, that in itself is precious. It is sacred. The writers that I appreciate the most incorporate that into their narrative.

I go back to Ed Jones. What is so marvelous about him is that he helps me understand my very simplistic idea of a story: sometimes there’s one character with one experience, but within his stories, there’s always a remembrance, there’s always this other incident that happened several years back—and they’re all intertwined. There’s often someone at the center who is listening and observing, but they’re receiving many, many stories, and they’re constantly in a position about whether they’ll share it with somebody else—or not.

“Fieldwork” is as close to autofiction as I get. It’s about my father, Antonio, when he had a stroke. Ultimately, it’s a story about a passive listener: the character of his son has nothing to do but listen; that’s his job. I wanted the mother’s last line to undermine him a little bit: “Men don’t know how to suffer.” That character’s my mother, and that’s her line. She has such a wonderful ability to toss off these lines with such depth and emotion and resonance that I can’t do anything but record them.

Shea: Labels are, as always, problematic, and reviewers often identify you as “gay and Chicano,” both true—yet maybe reductive? I love Sandra Cisneros’s letter to the editor in the New York Times in response to a review of The Faith Healer of Olive Avenue. She points out that the reviewer was trying to be “kind” when describing your work as “too rich to be classified under the limiting rubrics of ‘gay’ or ‘Chicano’ fiction.” She retorts: “Imagine if I were reviewing John Updike and said that his stories are far too rich to be classified under the limiting rubrics of ‘heterosexual,’ ‘upper-class,’ ‘white’ fiction; they have a softly glowing, melancholy beauty that transcends those categories and makes them universal.” First, were you offended by the reviewer’s classification? But more important, perhaps: are these labels still being used? I note their absence in the Los Angeles Times piece on The Consequences that appeared recently.

Muñoz: I wasn’t offended by that review [in the New York Times], mostly because I’ve seen those tags before. Sometimes I need to use them to identify who I am in my own spaces. But I appreciated Sandra’s letter because if that’s the only thing a reviewer or critic may go for, it sidesteps the need to even take on what the story is doing. A word like “universal” is meant kindly, but it’s avoiding the work. It’s not allowing the stories to be independent in their own world.

Reviews of The Consequences haven’t really come out, so I haven’t seen if people will go there. Will I be watchful? Yes, but I’m not sure if I’ll have much of a reaction if people do. I think there was a little bit of that with my novel because there were questions about what a gay Chicano writer was doing writing about Hitchcock. That’s a great question—but why don’t you answer it? Don’t just raise it: think about what that might mean.

Shea: When I asked Helena about these tags, she agreed that the labels themselves are likely to go by the wayside—with the caveat “even though the biases will not.” She commented that in her own work, anything about the working class, about poverty, is often classified as being “overtly political.” Do you agree?

Muñoz: She points to the more persistent problem: the labels might get minimized, though the assumption that a story about the working class is narrow by definition is the harder barrier. That might be why I’ve been so attentive to form and try to demonstrate some other angle I might take in my narratives. Sooner or later, if there are enough stories, critics have to say something beyond the labels, and they too might recognize the biases that have been in operation.

Shea: Most of your stories take place in the 1980s (a few into the 1990s) with immigrants and migrant workers at the heart. How do you think today’s border controversies (for lack of a better word) will affect how they are read and understood, particularly by younger people who were born in the twenty-first century?

Muñoz: I’m actually not sure, but right now what has felt most urgent to me has been a sense that so little of those experiences of that time in that place are in our literature, so I’m helping to fill in that gap. There’s a lot of work to do. There are plenty of other writers who can speak to the contemporary moment.

There’s something really odd about the 1970s, ’80s, and early ’90s, and I can’t quite put my finger on it. Some of it has to do with the 1986 Naturalization Act. I was fourteen, and that completely changed our home because of how it affected my dad and a lot of the people I went to school with. Suddenly, your friend’s mom got deported. Those were important moments when we were young that we didn’t understand as having global implications. It was happening because it’s a global issue, not just us in a little town. That’s why I keep circling back.

Also, when it comes to the queer experience, the coming-out stories, students today are often puzzled by a character who is closeted or who is not free with expressing who they are. I have to remind them that despite your own contemporary experience –the moment you step out of the closet—not everybody has come out with you. The closet remains, and it’s still very powerful even now in a small town like mine.

Shea: You’ve commented about your decision to become an academician, a teacher, your reservations about doing that—and Helena’s wise advice that you should embark on that career only if you could commit to being “in service to your students.” When talking about your teaching, you’ve said your job “is not to help people understand my work, but to cultivate a respect for why I do the thing that I do.” Is that part of “service to your students”?

Muñoz: Yes, because many of them, once we have a comfort with each other, see my enthusiasm for literature and story-making, then begin to ask how to talk to their family about being a creative writing major or an English major. We can start to have those conversations. To see in another, as I did with Helena, a deep love for literature and a belief that it is of use to you, that’s the transformative possibility. The great silver lining in being in academia for the past fourteen years is having those great discussions with undergrads about why literature is so enriching.

To see in another a deep love for literature and a belief that it is of use to you, that’s the transformative possibility.

Shea: Recently, Kyoko Mori published in LitHub a wonderful essay called “A Difficult Balance: Am I Writer or a Teacher?” She wrote: “In a political climate that doesn’t respect literature, art, history, science, or any serious examination of facts and ideas, creating and maintaining such a space week after week is a necessary act of resistance. It’s an attempt to ensure that we still have a world in which people care about anyone’s writing.” Would you call being a teacher of literature and writing an act of resistance?

Muñoz: Oh, absolutely—that’s beautifully put. My students are also seeing that their very willingness to be in a place of learning is being challenged; they’re second-guessed about everything. Some of it is what major are you choosing, but it’s getting to the point of asking why you’re in a university at all. Some of the doubt I’ve experienced in the past few years is connected to the stress of work. I’ve often said that if I didn’t have a university job and I still worked in New York in publishing, I would have stepped away from writing for a good while, but when you’re in a university, you can’t. What am I writing and why am I writing? How is this contributing to the greater conversation? Do I listen to myself or the conversation around me? It has been a time of great skepticism. Being in academe doesn’t necessarily sort it out, but sometimes the classroom can be a great refuge.

Shea: Last but far from least—what’s your best hope for The Consequences?

Muñoz: That’s a tough question. I don’t know how to answer that. I’ve been very vocal to plenty of my friends about how hard it’s been to write—but I produced something that I’m very proud of. In many ways I refused the doubt that the book is too sentimental, too regional, too limited. I’m really proud of embracing home the way I have. I just hope it reflects well on the people who taught me what I know.

September 2022

Author’s note: Special thanks to Carlos Escobar for his advice on the interview. The interview with Muñoz was conducted via Zoom and email in September 2022. The conversation with Viramontes, also in September 2022, was via Zoom.

“What Kind of Fool Am I?” (an excerpt)

I lied to myself all my life. To my mother and father, less so. But that was only because my father rarely spoke and my mother hardly listened. I didn’t lie often, but I lied about what mattered. It fell on me to explain my little brother to them, why Teo did the things that he did. He wasn’t a terrible child by any stretch, but he was stubborn and had to be told twice about everything. I had the notion that I would have no such allowances, and that any punishment inflicted on Teo would come doubly so for me. One time, when we were very young, we tailed our mother at the five-and-dime as she lingered among the fabrics. We played among the draped displays, pulling cloth across our faces like bridal veils, until our mother shooed us away, worried that we would dirty or tear what she couldn’t afford. In the cosmetics section, while our mother was preoccupied with the saleslady ringing up her purchase, I watched Teo pocket something. He did it quickly, I remember, and I had the sense that he hadn’t even really considered what he had taken. He guarded his treasure with a fist in his pocket so deep that he looked like he needed to pee. At the front counter, the clerk kept glancing at him in alarm, rushing our mother’s purchase. I was sure the clerk had found him out, so I drew Teo in, shielding him from my mother, and yanked the small plastic case from his pocket. I gave him a look that he seemed to understand. He kept quiet, even when our mother startled us both by slapping me in front of the clerk before placing the case on the front counter. It was eye shadow, I would learn later, when I studied the clutter of my mother’s dresser and learned the names for things, sometimes with Teo at my side, sometimes in a mood that was all my own.

This was in a little town called Mathis, Texas, and I was twelve when I first started to realize that I lived in a place that wasn’t ever going to change much. Now and then, our father would drive the family to Corpus Christi to shop at Woolworth’s or to sit in the orange plastic chairs of some state services office. The trip was only thirty minutes or so, but I could feel the air change, thicker and saltier, and the city seemed to get busier every time I saw it. Our father must have sensed my thrill at seeing the blue-green line of the Gulf horizon, and after errands he would loop by the bay so we could point at the sailboats bobbing or gaze up at the rib cage of the bridge arcing us across the harbor. I had no deep imagination then about the water. It was only an end point, a place that stopped you and showed that there was no choice but to turn back to the sun-white streets of Mathis. So lost was I whenever I saw the Gulf that I failed to notice that my brother was quiet, too, and searching in his own way.

Teo must have been planning his someday even then. Where I took note of the wide Gulf and the tall buildings on the water’s edge, he must have been seeing the nightclub fronts shuttered against the daylight, the neon signs hungry for dark. We’d pass those places from one end of the city to the bay, and I noticed my father’s attention on the road, my mother just as stern. This was always where I would start looking for Teo, years later when he was sixteen and his impatience ran him away.

Editorial note: “What Kind of Fool Am I?” was first published in American Short Fiction, Issue 76, and appears in The Consequences: Stories published by Graywolf Press in October 2022. Copyright © 2022 by Manuel Muñoz. All rights reserved.