Born in Tehran: A Conversation with Porochista Khakpour

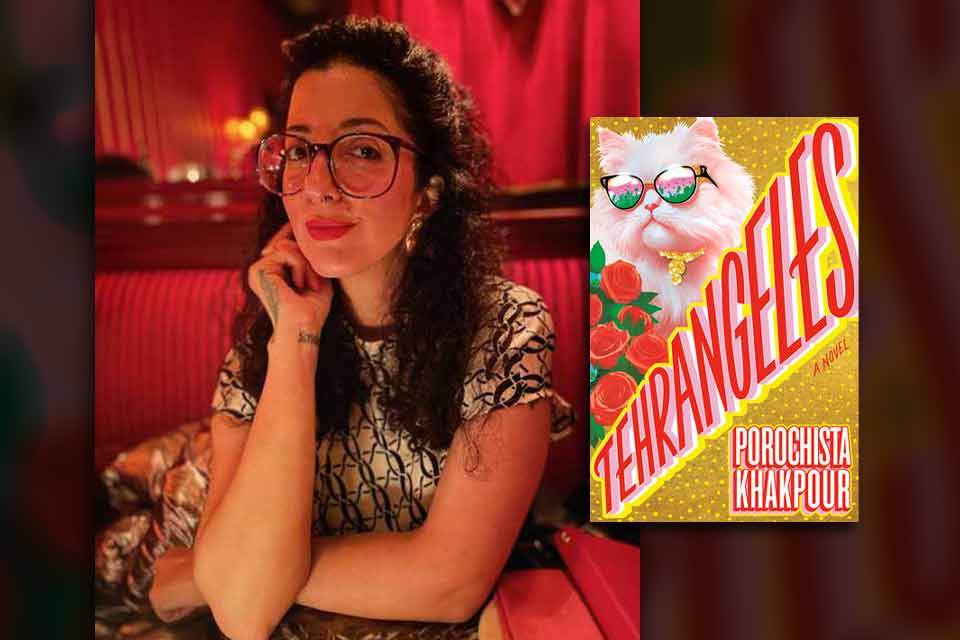

In June 2024 Pantheon published Tehrangeles, Porochista Khakpour’s latest novel (see WLT, Sept. 2024, 73). The novel satirizes social media culture and turns the lives of four Iranian American influencer sisters upside down as they are faced with the pandemic and their own secrets and shortcomings, beneath the perfect avatars they had hoped to display for reality audiences to admire. The novel was named a Best Book of the Year So Far by Vogue, Harper's Bazaar, Vanity Fair, and W Magazine and a Most Anticipated Book of the Year by TIME, New York Post, The Week, The National, Nylon, Bustle, Our Culture, Lit Hub, The Millions, Electric Literature, Katie Couric Media, Seattle Times, Chicago Review of Books, Alta Journal, Write or Die, and Library Journal.

In June 2024 Pantheon published Tehrangeles, Porochista Khakpour’s latest novel (see WLT, Sept. 2024, 73). The novel satirizes social media culture and turns the lives of four Iranian American influencer sisters upside down as they are faced with the pandemic and their own secrets and shortcomings, beneath the perfect avatars they had hoped to display for reality audiences to admire. The novel was named a Best Book of the Year So Far by Vogue, Harper's Bazaar, Vanity Fair, and W Magazine and a Most Anticipated Book of the Year by TIME, New York Post, The Week, The National, Nylon, Bustle, Our Culture, Lit Hub, The Millions, Electric Literature, Katie Couric Media, Seattle Times, Chicago Review of Books, Alta Journal, Write or Die, and Library Journal.

Shohreh Laici: Tehrangeles’s opening writer’s note is an ode to all that is wonderful and glorious about Iranian culture; it brought me to tears when you read it for its poetry in Philadelphia. Was this where the novel began for you, in finding the language for the characters? Or was it deeper still, in the breaking and division of what it meant to be both Iranian and American in the world that the novel inhabits?

Porochista Khakpour: Thank you so much for your comment on that intro. I loved writing it, but you might be surprised to know it was actually the last part that I added to the book. It’s not even in the galleys! I added it in last-minute because I didn’t want the reader to enter the Tehrangeles-on-steroids world of Roxanna’s without some explanation, or maybe even some intervention. . . . For me, Mina is the antidote to all things Roxanna, and I see the POV here as a tug-of-war between the two of them. Mina wants a meaningful life, and Roxanna wants to resist that as a form of survival.

Roxanna—like many Tehrangelenos—is very concerned about survival, and that means mainlining the worst of American culture in so many ways. You could say this is a “blind spot” of Mina’s, perhaps. She—like me—often has her head in the books, in dreams of social justice and activism. She’s entrenched in the promise of a better world, while Roxi very much lives in the very terrible, very real one. One could say Mina is much more Iranian and Roxanna much more American, but it’s more complicated than that. In a way, Iranian and American psyches are sort of dispersed between every character, including Pari the cat! I kept everything quite complicated, as I felt that was the most honest and authentic way to talk about the Tehrangeles landscape and psychology.

Laici: You seem to have taken language in new directions, exploring how texts and social media feeds might be represented in the topography of the page. How important was getting this visual and spacing for the aesthetic and understanding of this novel?

Khakpour: Thanks for noticing that also! I came into it thinking I’d have a lot of limitations, dealing with a conventional mainstream Big Five publisher. But my team was great about it. I got away with using some emojis here and there. We had the diamonds instead of the conventional asterisk. We even had the couple of pages of pure Persian/Farsi untranslated! I would have gone even further, of course—my aesthetic veers closer to chapbooks and experimental art books, but I’m always broke so I need to go with major publishers that offer at least somewhat decent advances. (I am still on the low end of advances there, though.)

Usually, there’s only so far you can go with graphic displays. I remember, for my second novel, I wanted a wax-paper insert with a tiny font, a catalog of all the birds on earth alphabetized. Bloomsbury—an indie but a big one—didn’t even have that discussion with me, but I’ll always have that image in my head. In my head, Tehrangeles is always a tad different—the cover would be even more campy and neon, maybe the paper would be a vulgar pink, I might have even added scratch-and-sniff Candyland stickers or something. You know, if I had the budgets to match my vision, everything would be quite over-the-top! I haven’t made it big enough to get my way on that scale, ha! Maybe one day when I’m dead someone might try it all. I’ll probably sell more books dead than alive!

Laici: If we compare Tehrangeles with your early novels, its scope and style are radically different. Are you purposely trying to find new ways to break conventions—or is this simply the result of following your research and being true to the world and universe of the characters you’ve created?

Khakpour: I think every book I’ve written is quite different. They have some things in common: with the novels, there’s Iran, of course. But I think there is always some kind of maximalism—in my first book it was in the prose, in my second book it was in the plot, and here it is very much alive in the theme (and setting and characters, of course, too but the theme carries it). I don’t know if Tehrangeles breaks more conventions—some have found it more conventional or at least more commercial than, say, my second novel. It will be interesting to see what people think when my short-story collection is out, which to me might be my best book. Many of those stories have cooked for over two decades now.

Laici: You lived most of your life near Tehrangeles—and not in this uber-rich and luxurious lifestyle. Was inhabiting this world and satirizing the universe a commentary or a forewarning of where greed and the 1 percent may be leading the world?

Khakpour: I like how you framed this question. Yes, geographically speaking, I lived close enough. About twenty miles away, forty minutes on the 110 to 10-W freeway. But California is funny like that—every part of it could be in any entirely different state and sometimes an entirely different country. It has so many subcultures and micro-universes, really. I had a job in Tehrangeles. I worked twice at the same boutique on Rodeo Drive, which many might say—along with Westwood Boulevard—is one of the most famous streets in Tehrangeles. My family and I often went out to eat or went to the shops there on the weekends. It was a presence in our life no matter what. I suppose one could say it’s a commentary on my past, but maybe it’s a commentary on the communities I was essentially adjacent to, although in a better world I would have counted as a Tehrangeleno. It’s the other Tehrangelenos that would say I would never make the cut. I wasn’t a West Side person, I wasn’t wealthy, I wasn’t conservative in my politics—I could never cosplay as them even if I wanted to.

Which leads to the second part of your question—yes, I do think thematically you are correct. In so many ways I thought of this as a cautionary tale about the excesses of capitalism—or rather, capitalist horror fiction. But people are reading it in all kinds of ways, which is frankly fascinating.

In so many ways I thought of this as a cautionary tale about the excesses of capitalism—or rather, capitalist horror fiction.

Laici: The novel is also set during the pandemic, yet you began writing it well before. Was setting Tehrangeles during the pandemic and including that situation in the text an epiphany for you, and how did it change the original direction of the novel?

Khakpour: I had done many drafts of this novel since 2011. It was sold on proposal plus one hundred pages with Brown Album in 2018 to Knopf Doubleday. I actually had only wanted to sell the essays, but Dan Frank at Pantheon was really excited about Tehrangeles and felt a two-book deal would allow me to have a heftier advance, so that was something. But I kept drafting it, and I always felt like the setting was an issue for me, while the characters were very much set in stone.

I spent the early pandemic living in the epicenter of the United States’ Covid crisis: Queens, New York. It was very stressful. I ended up losing seven friends to Covid and Covid-related illnesses, but I also started to find the spectacles around the pandemic to be perfect for satire—the failures of our government and the media, the American right wing’s meltdowns and the rise of QAnon conspiracy theories, the content creators and their horrific superspreader parties, etc., etc.

I thought this could be an interesting setting, especially since Iran was involved in this era so bizarrely—there was Iran being one of the countries with the worst outbreaks for a while after China and Italy, and of course all the possibilities of war with Iran after Soleimani’s assassination in January 2020. So, once I had this, it gave the novel the focus it always needed. Plus, these six very distinct family members all trapped in their mansion together was too good to be true. So, while the early pandemic was a horrific time to live through, it provided me with the ideal container for my plot and all its complications. I thought it was at least worth a draft. And when I was done, I knew it was the right one.

While the early pandemic was a horrific time to live through, it provided me with the ideal container for my plot and all its complications.

Laici: Many readers are raving about the novel and commenting that they’ve read it in only a few hours. Does it bother you that something that took you so many years of research and understanding can now be part of the same consumer culture you are criticizing?

Khakpour: Ha, it’s a funny thing to hear! I’ve only heard it about this book and my memoir, Sick. No one thought this about my first two novels. I actually kind of love it. When I have that kind of “page-turner” experience with a book, I love it. I don’t really think of it as consumer culture, because—for me—the time it takes to read a book has nothing to do with its artistry. Or rather, it’s all consumer culture. America! We are all entangled in capitalism in ways that we never signed up for—unless of course you’re the Milani family, and then you very much signed up for it.

Laici: I have spoken to many artists who have said that after spending years on a project and finally completing a masterwork, they are no longer the same person. In some ways they had to let themselves go as mad as their characters, or just mad in general, with where the imagination might lead them. Do you feel that you have been forever changed by Tehrangeles?

Khakpour: This is such an interesting question. Is it a disappointing answer to say no? I mean, I am not one of those writers who says my new book is always my favorite book. I often feel very suspicious of my own books in those intense book promotion seasons. The experience makes me kind of sick of it, and then I start thinking of my other books. I felt most changed in good ways by my first two novels and most changed in bad ways by my third book, the memoir Sick. Sick made me very stressed out—it turned out that even though the response was largely good, I didn’t enjoy that level of exposure, and I constantly felt very misunderstood by the attention. Not to mention how much cyber-harassment I experienced.

But my first two novels feel very much like my own story, whereas Tehrangeles is me grappling with the stories of other Iranian Americans. I needed it out of my system, but I only miss Mina Milani from that book, and maybe Homa, the mother, too. In general, I feel like every book of mine is different, even it if there are some recurring themes and concepts, so I truly hope I would not feel changed from book to book. I think, to be honest, reading books transforms me more than writing them. Maybe it’s because I've been practicing writing books since I was in elementary school.

I think, to be honest, reading books transforms me more than writing them.

Laici: When you visit home now, does it feel like home? Or do you feel like you’re in your novel Tehrangeles?

Khakpour: I was just home for the book tour, and it was my first time back in quite some time. I had sort of missed Los Angeles, it turns out, which is not always how I feel. But I wonder if the fun aspects of the novel and the sort of weird experience of book touring made me lean into the surreal aspects of the city. A Gen Z friend of mine took me to Erewhon, and we rated fancy waters for a TikTok video. I hung out by the pool at The LINE Hotel and watched content creators make generic videos. I ate ridiculous amounts of Persian food with my family. I got a ride from LAX from a young transplant who decided to smoke some meth in the car, totally out of nowhere. LA, baby! It was wild.

New York always feels the most like home because I came here at age eighteen and it really made me a writer. My parents chose LA for us; I chose New York for me. But LA is a much more interesting topic for books than New York, I often feel. My mixed emotions about Tehrangeles, for example, are much more interesting than all my instantly generic platitudes about loving New York. New York is all its clichés and more, in a good way, while LA has those too—but in the bad way that makes for great comedy.

Laici: Was writing Tehrangeles your way of breaking free from the Islamic Republic in some ways? A break from all that was before and the societal standards and expectations of the past or present? Or even from the Iranian diaspora in general, which has not had the best track record in collective support, whether inside Iran or without, since the community is so divided on so many issues?

America is the real problem in my novel, though I think only one or two characters really get that.

Khakpour: I think situating myself in relation to the Iranian diaspora was challenging. It has disappointed me so much all these years, especially the red-pilled / conservative / neocon / MAGA / Republican worlds! They are very loud. And the way they love sanctions and often want war—I find them very much in opposition to the hearts and minds of those in Iran. Iran and its Iranians always make sense to me in a way the diaspora does not.

The regime in Iran is not something I ever identify with—I’ve been very literally protesting them since I was a child. It’s what made me an activist. I hope I never ally with them in anything I write! But Tehrangeles critiques American culture more than anything. Iranian Americans certainly did not invent American capitalism, even though they may greatly identify with it. America is the real problem in my novel, though I think only one or two characters really get that. But it’s obvious to me. And it’s not a marg bar Amrika energy but a how did we get here and how do we get out energy—especially since there’s nowhere to go. The homeland is sealed off. We’re stuck. And we largely don’t have each other. Once again, like the pandemic setting, an awful predicament for real life—but an irresistible one for art!

September 2024