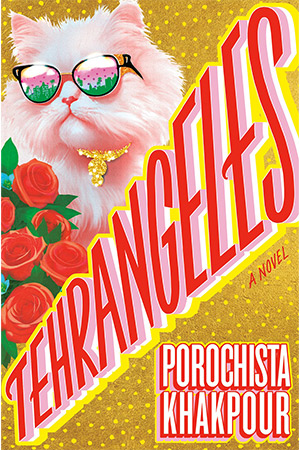

Tehrangeles by Porochista Khakpour

New York. Pantheon Books. 2024. 308 pages.

New York. Pantheon Books. 2024. 308 pages.

Iranian American authors are often called upon to represent their culture and people against a steady stream of unpleasant news headlines about Iran and its government. Some seek to rectify the image of Iranians by depicting the more tender and cultured aspects of Iran—its long and poetic literary tradition, its globally celebrated cuisine, or the striking beauty of its women. But in the act of defending and proclaiming Iran’s “greatness” against a backdrop of bad news, we sometimes lose the nuance and tension inherent in being part of Iran as well as part of somewhere else.

Porochista Khakpour’s third and most recently published novel, Tehrangeles, smartly and satirically takes on some of those tensions, while also pointing to the larger experience of what it means to be Iranian in contexts and cultures outside of Iran. Like her previous novels, Sons and Other Flammable Objects (2008) and The Last Illusion (2015), Khakpour indeed gives us something of Iran, or at least the trace of it, in fresh form. Rather than trying to correct the image of Iranians, however, she launches headlong into representing the most flamboyant and perhaps better-known attributes associated with Iranians in America. The result is a parody of Iranian Americans in Los Angeles, endearingly referred to by the largest population of Iranians outside Iran as “Tehrangeles,” which alludes to images of Iranians that many Americans will have likely consumed in the reality series The Shahs of Sunset (which aired on Bravo from 2012 to 2021) and also flirts with the Keeping Up with the Kardashians reality TV series. But Khakpour’s depiction of Iranian Americans in the cast of the Milani family is far more complex, rich (in both senses), and also funnier than anything we’ve read.

In her acknowledgments at the end of Tehrangeles, Khakpour identifies the impetus for this novel as a challenge to the publishing industry that often foists upon writers the need to write for readers to whom editors and agents want to sell their books. Khakpour says that at the suggestion of one of her editors, she decided to write a “a more realist story with more women characters” but that she had to “hate-write” her way through it because her characters were part of the ilk of Tehrangeles she most disliked: the crazy rich Iranians (yes, a reference to Kevin Kwan’s Crazy Rich Asians whom Khakpour thanks in her acknowledgments).

In several interviews, and at a recent reading in San Francisco, Khakpour also describes the novel’s origin in her experience of being a young shopgirl in a fancy clothing and accessory store on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills; the shop was frequented by many wealthy Iranians, who in most cases came from Iran after the 1979 revolution and brought with them the attitudes and wealth of the Shah, who was ultimately deposed by the revolution. Rather than meeting Khakpour’s friendly shopgirl greetings in Persian from the other side of the counter, however, she describes these painful experiences of encountering “her people” as a form of class prejudice and old-fashioned snobbery. It is those earlier experiences of wealthy Iranian immigrants in Los Angeles that became the fictionalized crazy rich Iranian Milani family.

The Milanis are part of what might be considered the classic Iranian diaspora experience of Los Angeles. Immigrant mother and father, Homa and Al (Americanized from Ali), and their four American-born daughters—Violet (who changed her name from the Persian word for the same flower from Banafsheh to avoid the ridicule of those who cannot pronounce), Roxanna, Mina, and Haylee (Americanized from Haleh)—are a far cry from the tired defense of Iranians and Iranian culture against the repressive regime in Tehran. Instead, Khakpour squarely, and humorously, addresses how painful it can sometimes be to be different, to be immigrant, to be “other,” in a society that prefers the “extractive” to the whole, even when you’re ridiculously rich.

Set at the moment before Covid-19 becomes a global pandemic, Tehrangeles hones in on some of the most palpable issues that plague Iranian families which have both wealth and deep anxiety about being seen (and seen in both the sense of being visible but also in terms of appearing powerful and important). And being seen is very much on the minds of the four Milani sisters, whose father catapults the family to the status of uber-rich as the inventor of the “Pizzabomme” (Cinnabon meets hotpockets) snack empire; they have just landed a deal for a reality TV show that promises greater fame and visibility.

While the oldest sister, Violet, is already quite visible as a model, her two younger sisters are potentially more viable as main characters for the show, and they know it. Roxana, an overly ambitious influencer who prides herself on being her dad’s favorite, and the youngest sister, Haylee, who is obsessed with wellness culture and clean eating, both become caricatures of our culture’s social media influencer culture—something Khakpour writes deftly about in this novel. Mina, on the other hand, is the more “practical” of the four and is more invested in anonymous online stan culture than her own face on TV. Their lives are turned upside down by the pandemic as they navigate life ensconced in their wealthy Los Angeles estate, complete with the white American “help” and their spoiled Persian cat, Pari. In the time when they most want to be celebrated and seen by the outside world, they instead find themselves confronting their secrets, hidden desires, and painfully visible vulnerabilities.

Khakpour’s book is indeed a novel for our time. She smartly writes in a way that exposes how wealth and the obsession with being seen, either by pop culture or the social media ecosystem, leads to its own dark sides. Her funny albeit critical narrative position toward Iranian Americans, particularly those of the ultrarich variety, who try to become something more, something else, something other than Iranian, offers an important critique of assimilation as well as class. In doing so, Khakpour also exposes how microaggressions as well as cultures of racism, xenophobia, and erasure play out in the identities of this one “hot mess” of a family even in the age of hypervisibility. Ultimately, she tells us in an entertaining and engaging way that appearance and appearing just aren’t enough.

Persis Karim

San Francisco State University