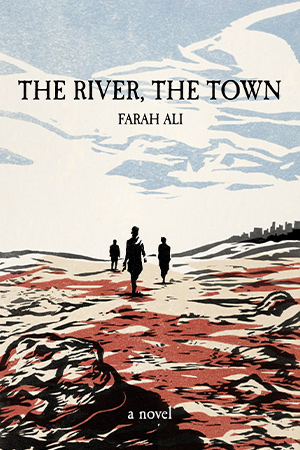

The River, the Town by Farah Ali

Ann Arbor, Michigan. Dzanc Books. 2023. 216 pages.

Ann Arbor, Michigan. Dzanc Books. 2023. 216 pages.

Farah Ali’s debut novel, The River, the Town, chronicles the journey of Baadal and his family amidst economic and environmental strife, making the reader question what parts of a self are able to survive and still yearn during the collapse of larger systems that sustain humans. While the river, a powerful allegorical force, dries up and migration becomes a necessity, Baadal and his kin battle the unforgiving landscape, which seems to continually betray them as they struggle to live and thrive. Ali is a Pushcart Prize–winning short story writer, and her collection of short stories, People Want to Live (2021), includes some of the most nuanced portraits of life in Karachi I’ve encountered in Pakistani fiction published in English.

Ali privileges exploring the yearnings of her characters over their eventual fates, and in her hands the characters are protected from becoming voiceless victims of systemic oppression. Her lyricism and fierce formal clarity in this polyvocal novel protect the characters from becoming tropes or mere symbols. Still, there is a larger and potent environmental message here even though we are in an unnamed place: the villages are called chota gaon (small village), purana gaon (old village), doosra gaon (other village), etc. One cannot but resist drawing parallels between the landscape Ali so diligently builds to the plight of Pakistani cities in the last two decades, cities ravaged by water shortage, poverty, environmental disasters, and loadshedding. The novel is interested in the politics of poverty, the problematic representations of the poor in arts and media, and by keeping places unnamed, Ali seems to be saying this is not a regional matter. This concerns everyone. Nectar in a Sieve, Kamala Markandaya’s seminal novel, certainly came to mind as I made my way through the pages, but in Ali’s constructed universe, nature is not some medieval force, mercurial and playing with the destinies of characters arbitrarily. Instead, we have the clear impulses of neoliberalism using up resources, encroaching on land, waging war on the poor.

Reading about poverty can require a certain kind of unflinching patience, but the specific daily rituals of indigence are not presented here for mere spectatorship. A larger artistic project begins to emerge very quickly. Ali looks at her characters and keeps looking, unwilling to run away herself or allow them that luxury, as if looking alone is the only thing that matters. As if an awakening needs to happen in the reader and not the characters of the novel.

Munib Khan

Lahore