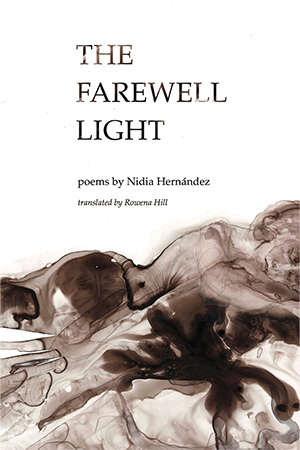

The Farewell Light by Nidia Hernández

Medford, Massachusetts. Arrowsmith Press. 2024. 158 pages.

Medford, Massachusetts. Arrowsmith Press. 2024. 158 pages.

Nidia Hernández’s debut collection of poetry is a lyric sanctuary, an invitation to meditate on the natural world and what its enigmas can teach us about our own humanity. The bilingual poems in The Farewell Light apply the inquisitiveness of a writer learning a new language to the carefully crafted lines, which are often as short as one word, inviting us to read slowly. And why shouldn’t we take our time? These poems are set against an invisible clock ticking, poignantly reminding us of the fleetingness of everything—the stability of the speaker’s home country, familial memories, and lost beloveds all retreat into the sea, like turtle hatchlings guided away from the shore.

One of the volume’s central themes is water. Water, like the river of the speaker’s childhood village in Venezuela, becomes symbolic for memory but also for erasure and loss: “I thought about everything / that has gone / like the water / everything was fleeing with the river.” The longer the speaker is away from her country, the greater the distance between memory and the present. Or when remembering a journey she had taken with a loved one, rain becomes the watery medium through which everything is erased: “The rain and the journey were saying goodbye / while you and I spoke softly.” Hernández’s language is philosophical but also filled with moments of distilled clarity: “you touched with your fingers / the imaginary center of things / as my mother did when she wanted to speak of realities.” In “The manuscript of the rain,” she asks if writing on water is “illusory,” a moment of poetic self-awareness in which she points to her own ambivalence. I can’t help but think here of Marianne Moore’s imaginary gardens with real toads in them. The power behind Hernández’s poems is in the discernment that rises out of her dreamlike images.

Many of the poems in The Farewell Light have a surrealist quality. The narrative in “A blind spot” centers on a dream in which the speaker is visited by her mother. Through surreal imagery that engages all senses (“[horses] were molding the sound of the wind”), the poem artfully captures the experience of dreaming about a lost loved one. We witness how the loss is renewed when her consciousness disrupts the suspension of disbelief afforded by the dream. Halfway through the poem, she begins to shift to reality, to a realization that her mother’s visit is actually a departure: “I knew we wouldn’t see each other again.” The central theme of water again becomes a vehicle for grief:

I wanted to smile

but I cried

because I didn’t have her

because of my silence

I cried until I was water

Until I was sea

And I began to swim

toward the depths

to blend

with the stones’ light

and disappear

The poem ends with an image of Neptune appearing, and a plea for him to stay. It is apt that Neptune, Roman god of the sea, becomes a solace for the one for whom water is associated with home.

Much of the second half of the collection shifts toward images of the writer’s arrival in snowy Boston, winter becoming a landscape through which she can reflect on what has been lost and gained in immigrating to a new country. The second section opens with the poet asking the reader to come walk through the snow, which is compared to a “memory / of a flock of gardenias / rotating on themselves in the air,” a prime example of the metamorphosis that an image can take under Hernández’s hand. At other times, snow is a refuge from the world that the speaker only witnesses from the window, a generative pause that provides an opportunity for new meaning. The poems in these later sections reflect the duality of navigating a foreign country, a mixture of isolation with the desire to embrace a new language. In “I love confusion,” she boldly states: “Confusion / looks at me kindly / it knows that everyone avoids it / I don’t.” Confusion to this poet, a translator and lover of language, is merely an opportunity for deeper understanding, for stumbling into a great discovery.

Along with its ode to language itself, the book nods to Hernández’s vast knowledge of poetry, with several poems titled after literary heroes such as Edith Sitwell, Patti Smith, and Emily Dickinson. In “Walt Whitman,” she imagines the grass at an arboretum as Whitman’s beard, “longer lasting / than all the stars.” In this tender nod to “Song of Myself,” Hernández echoes Whitman’s wisdom. Against the passing of time and the anticipation of loss, she finds comfort in the immortality of words. In a poem dedicated to Peruvian artist and writer Jorge Eilson, she describes meeting him both in life and in a dream, later recalling his lines, “True poets appear / without anyone noticing.”

This is just how I imagine Nidia Hernández making her appearance, a writer who has already offered so much to the literary community, making her subtle debut. I hope the world will now take notice.

Patricia Guzman

Georgetown University